Happy Monday! Let’s have a great week, all right?

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

Massive protests erupted in cities across Cuba Sunday, with thousands taking to the streets to demand an end to the country’s decades-old communist dictatorship. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said last night the United States “would strongly condemn any violence or targeting of peaceful protesters.”

-

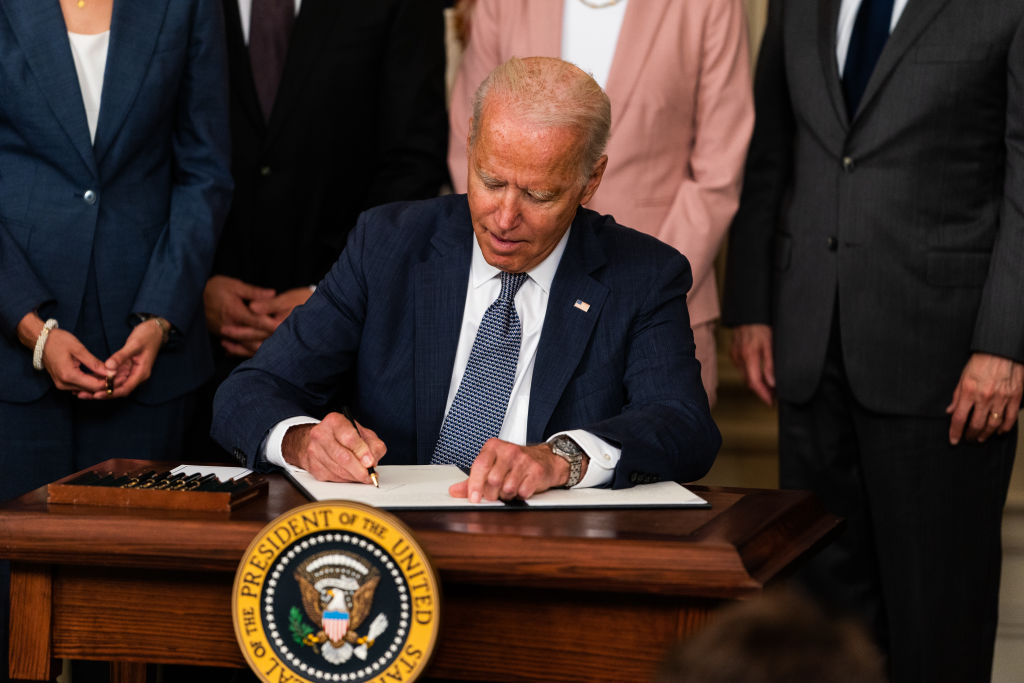

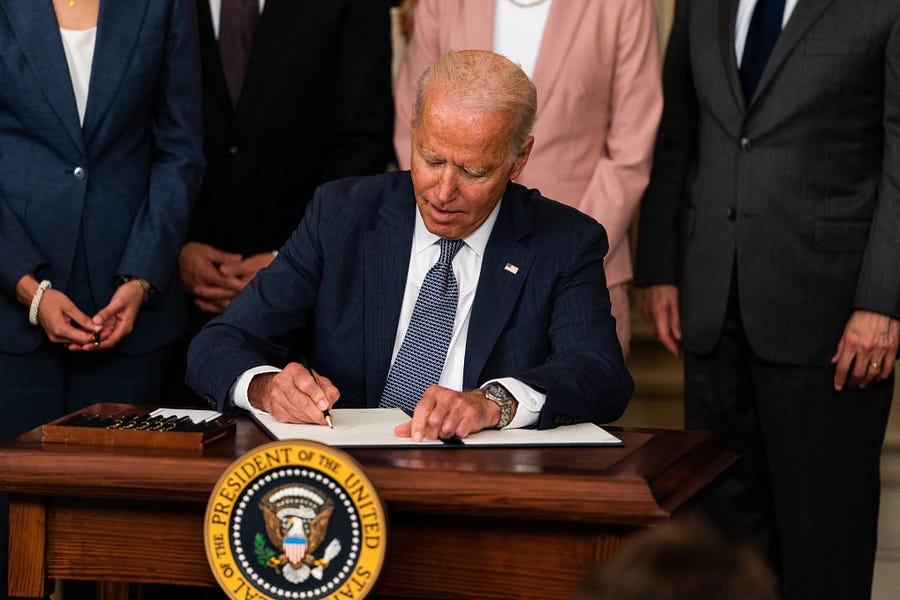

President Joe Biden signed an extensive executive order Friday—including 72 separate initiatives to be carried out by more than 12 federal agencies—aimed at combating what he deemed anti-competitive policies and practices in different American markets.

-

Haiti’s government under acting Prime Minister Claude Joseph has identified 28 suspects—including two Haitian-Americans and more than a dozen Colombian nationals—in connection with last week’s assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse. At the request of the Haitian government, the White House announced plans Friday to send FBI and DHS officials to Port-au-Prince to assist in the investigation. The Biden administration, however, has thus far held off on sending U.S. troops to the region.

-

The Centers for Disease Control relaxed its education-based COVID-19 guidelines on Friday, advising schools not to require that vaccinated teachers and students wear masks.

-

The White House said Friday that President Biden spoke with Russian President Vladimir Putin about the ongoing ransomware attacks originating in Russia. The White House’s readout of the call claimed Biden “underscored the need for Russia to take action to disrupt ransomware groups operating in Russia” and “reiterated that the United States will take any necessary action to defend its people and its critical infrastructure in the face of this continuing challenge.”

-

President Biden fired Social Security Commissioner Andrew Saul on Friday after the holdover from the Trump administration—whose six-year term was supposed to last until early 2025—refused a request to resign. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell called the move an “unprecedented and dangerous politicization of the Social Security Administration,” while the White House cited a pair of recent Supreme Court rulings as justification for his removal.

-

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement issued a directive on Friday ending the detention of undocumented immigrants who are pregnant, postpartum, or nursing.

-

The U.S. Department of Commerce on Friday added 14 China-based entities to its economic blacklist for their role in facilitating Beijing’s “campaign of repression, mass detention, and high-technology surveillance” targeting Xinjiang’s Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities.

Biden the Trustbuster?

We’ve written to you plenty in recent weeks about the rapidly shifting—and increasingly bipartisan—consensus on federal antitrust and competition policy, but the debate has been almost entirely focused on the tech sector. President Biden took a step on Friday toward broadening the discussion, signing an executive order encouraging more than 12 federal agencies to carry out a total of 72 different initiatives aimed at increasing competition and fighting what the White House described as a “trend of corporate consolidation.”

“What we’ve seen over the past few decades is less competition and more concentration that holds our economy back,” Biden said, alluding to President Theodore Roosevelt’s 20th-century trustbusting and referencing Big Agriculture, Big Tech, and Big Pharma by name. “Rather than competing for consumers, they are consuming their competitors. Rather than competing for workers, they’re finding ways to gain the upper hand on labor. And too often, the government has actually made it harder for new companies to break in and compete.”

“I’m a proud capitalist,” Biden continued, “but let me be very clear: Capitalism without competition isn’t capitalism; it’s exploitation.”

In a literal sense, the executive order is mostly toothless. Unilateral presidential action is inherently flimsier than congressional legislation, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Federal Communications Commissions (FCC)—the entities tasked with implementing many of Biden’s proposals—are independent agencies that do not take their orders from the White House. As such, words and phrases like “should,” “consider,” and “are encouraged to” appear in the executive order dozens of times.

But Alec Stapp, director of technology policy at the centrist Progressive Policy Institute, cautioned against dismissing the potency of Biden’s action. “The White House here serves as a coordinating mechanism, and it’s a public signal of what the Biden administration wants to prioritize,” he told The Dispatch, noting that three of the five current FTC commissioners are Democrats. “[It’s an] independent agency, but the Democratic commissioners want to be on the same team with other Democratic leaders in the party.”

“I wouldn’t undercut the power of the bully pulpit here, even if there’s not actual binding legal ramifications in this executive order,” he added.

So what exactly is Biden “encouraging” various federal agencies to do? We obviously don’t have the space to get into all 72 initiatives here, but the order—heavily influenced by Tim Wu, who was brought onto the National Economic Council to address technology and competition policy—seeks to affect the health care, transportation, agriculture, internet service, technology, and banking industries, as well as the labor market.

It orders the Food and Drug Administration to allow cheaper prescription drugs to be imported from Canada, directs the Department of Health and Human Services to let consumers buy hearing aids over the counter, and encourages the Justice Department and FTC to revise their merger guidelines for hospitals. It tells the Department of Transportation to look into requiring that airlines issue fee refunds if baggage is delayed or in-flight WiFi doesn’t work, and recommends the FTC limit farm manufacturers’ ability to block individual farmers from repairing their own tractors and equipment.

It encourages the FCC—currently deadlocked with two Republican commissioners and two Democratic ones—to restore net neutrality provisions and prevent internet service providers from striking deals with landlords limiting tenants’ choices. Most ominously for Big Tech companies, it calls on the FTC to establish “rules barring unfair methods of competition on internet marketplaces” and announces an administration-wide position of “greater scrutiny of mergers.”

Regarding the labor market, Biden’s order suggests the FTC ban or limit both non-compete agreements and “unnecessary” occupational licensing restrictions. “You realize, if you want to braid hair and you move from one state to another, sometimes you have to do a six-month apprenticeship, even though you’ve been in the business for a long, long time?” Biden said. “What the hell? What’s that all about?”

With so many different provisions crammed into one executive order, few are likely to agree with all of them. But Stapp argued many features of the order are what he calls “transpartisan.”

“Often in D.C. we look at bipartisan solutions as compromises, or splitting the baby. I get half of what I want, you get half of what you want,” he said. “On transpartisan issues, you look to see where interests actually align, and we both get what we want. Maybe we want the same thing for different reasons.” Occupational licensing and non-compete reform, for example, have deep pockets of support across the political spectrum. GOP Sen. Roger Marshall said last week that the agricultural aspects of the order will “help Kansas farmers and ranchers.”

The offices of Sen. Mike Lee and Rep. Ken Buck—two of the top Republicans on antitrust policy—did not respond to a request for comment yesterday.

But the business community came out hard against other aspects of the order. “Today’s Executive Order is built on the flawed belief that our economy is over concentrated, stagnant, and fails to generate private investment needed to spur innovation,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce Executive Vice President Neil Bradley said Friday. “In many industries, size and scale are important not only to compete, but also to justify massive levels of investment. Larger businesses are also strong partners that rely on and facilitate the growth of smaller businesses.”

Economists have conducted a lot of research over the past few years looking at whether the American economy has grown more consolidated in recent decades, reaching varying conclusions.

A 2019 study published in Oxford University’s Review of Finance found that the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index—a measure of market concentration—has increased in more than 75 percent of U.S. industries since the late 1990s. But a report from Joe Kennedy at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation—a nonpartisan think tank funded largely by corporate entities—pushed back on many of the initial study’s assertions, arguing that “despite the measured rise in concentration in some industries, in the vast majority of markets, it remains well below the levels that would normally trigger antitrust concern.”

Stapp largely agreed with Kennedy, arguing that, despite the Biden administration’s framing, the executive order has more to do with consumer protection and price regulation than it does antitrust and competition.

“There’s really good economic evidence that actually, in that narrow product market level, we’re seeing less concentration and more competition at the local level rather than the national level, and the local level is what matters to consumers, because most consumers make purchasing decisions at the local level,” he said. “So we’re not seeing this widespread crisis of monopoly power that the executive order is premised on, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t good ideas in there.”

CDC Issues New School COVID Guidance

We hate to be the ones to tell you, but the end of summer isn’t too far off. We’re only a month away from students starting to trickle back into classrooms, with the bulk of U.S. school districts gearing up to resume class in mid-August. As administrators hustle to get ready for their arrival, one familiar question hangs over all the ordinary preparations: How wary do schools need to be of the diminished—but not defeated—coronavirus pandemic?

The CDC, it turns out, has been pondering the same question. On Friday, the agency released new guidance for schools in line with other guidance changes they’ve made this summer: Unvaccinated people, including very young students, should continue to wear masks indoors, but vaccinated students and teachers can go without.

The CDC guidance is also blunt about the insufficiencies of the remote education students have been enduring, many for more than a year: “Students benefit from in-person learning, and safely returning to in-person instruction in the fall 2021 is a priority.” Even if schools are not capable of fully following the continued three-feet distancing recommendations, for example, the CDC says they should still reopen—while “layer[ing] multiple other prevention strategies.”

The guidance comes after a school year during which many schools were slow to bring kids back into the classroom despite glaring issues with remote learning—and an increasingly convincing pile of data showing reopenings weren’t causing COVID cases to spike.

It isn’t that kids can’t infect one another with COVID—by now, we’ve seen plenty of examples of minor flareups at schools that had resumed in-person instruction, sometimes forcing those schools to go remote again for a week or two to allow cases to go back down. But the population data also makes clear that reopening schools has not been a major driver of COVID in communities. Here’s the CDC again: “Neither increases in case incidence among school-aged children nor school reopenings for in-person learning appear to pre-date increases in community transmission.”

Even though kids can catch and transmit COVID, in other words, our in-large-part return to in-person schooling last year was a success. From an epidemiological standpoint, the anti-infection methods schools put in place—including masking, distancing, and limiting contact between different classes—worked. It wasn’t that every single instance of classroom transmission was prevented, but when it came to a community’s pandemic risk factors, school reopenings weren’t even on the map.

This was true even before vaccines had arrived on the scene and when virus transmission was rampant, so it stands to reason the prognosis would be even better now. And it is—with a few caveats.

The biggest (as it always seems to be when we’re discussing current pandemic risk) is that the virus currently going around is not the same one that was going around last school year. The Delta variant, which now makes up the majority of new COVID cases in the U.S., is more transmissible than its predecessors, and evidence is stacking that this is true for transmission among kids as well as adults. Last week, the Delta variant was involved in a superspreader event at a Texas church camp for sixth through 12th graders that resulted in more than 125 infections.

The spread of the variant is not a disaster in and of itself, but it does mean schools will need to remain particularly diligent to achieve the same level of virus suppression as before.

Since the CDC guidance is simply that—guidance—states are free to chart their own path. California state health officials, for example, announced Friday that their schools will continue mandating masks into the fall. “Masking is a simple and effective intervention that does not interfere with offering full in-person instruction,” California Health and Human Services Agency Secretary Mark Ghaly said. “At the outset of the new year, students should be able to walk into school without worrying about whether they will feel different or singled out for being vaccinated or unvaccinated—treating all kids the same will support a calm and supportive school environment.”

As we covered in May, several Republican-led states—including Texas and Iowa—have taken the opposite approach, forbidding public schools from requiring students or teachers to wear masks. Other officials, like Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, have suggested similar measures may be coming.

“I think when we go into August when the schools come back, it’s got to be a normal school year, and that’s what we should be doing,” he said last month. “I think most of them have already decided that kids should be able to go to school normally, that they should not be forced to wear masks. But I think that it’s important that we do that statewide.”

Worth Your Time

-

Jonathan Rauch had a conversation about his latest book with Peter Wehner of The Atlantic, and it is well worth your time. Why does American politics feel like it’s falling apart at the seams? “Polarization per se is not new,” Rauch notes, “but the more polarized a society gets, the easier it is to manipulate people by hating on the other side. Polarization opens the door for propaganda campaigns. And then propaganda exploits polarization, because it seeks to further divide the society.”

-

When the Supreme Court hears a case challenging Maine’s ban on public funding for religious schools, it will wade into a fraught debate—as old as the country itself—on what children should learn in the classroom. J.D. Tuccille gets into this can of worms, and why school choice might be its most viable solution, in his latest for Reason. “By resurrecting a century-and-a-half-old argument over whether families can choose for education funding to follow their children to religious schools that share their values, Carson reasserts the importance of choice in settling disagreements over what is taught in the classroom,” Tucille writes. “Choice plays [an important role] in empowering families to escape curriculum wars by leaving such battles behind in favor of peacefully selecting their children’s learning environments.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

In his Sunday French Press, David argues that a decline in close friendships—particularly among men—is creating an environment that makes repairing our political divisions impossible. “If the United States of America is the most powerful and most prosperous nation in the history of the world (and it is), then why are so many of its people so miserable and angry?” he asks. “Even if we’re wealthy and strong, we still need friendships like we need water and air. … When Americans lose the rich friendships one gains in the real world through shared lives, including shared hardship and shared suffering, we seek to fill the void through affinity (or factional) friendships we often start online.”

-

Some progressive groups are encouraging Democrats to adopt a less aggressive stance toward China over concerns it could undermine climate cooperation. Harvest and Ryan examined the dynamics at play in Friday’s Uphill.

-

Jonah’s Friday G-File was a meditation on nothingness, contronyms, and “how a lot of our problems today can be attributed to the confusion of words for things.” “We’ve moved from thinking texts are infinitely interpretable to thinking the world at large is just another text to be manipulated and reinterpreted,” he writes. “We’re creating a world where we think words have eldritch energies that can transform reality if we really, really mean it—and take as much offense as possible when people disagree.”

-

Last week marked the six-month anniversary of the January 6 attack on the Capitol, but the resulting criminal investigations are only just beginning to hit full stride. Sarah and Steve were joined on the Friday Dispatch Podcast by Scott MacFarlane, an NBC4 Washington reporter who has covered the proceedings extensively.

-

In the culture section over the weekend, Alec reviewed Marvel’s Black Widow, and Declan reviewed Tim Robinson’s sketch comedy show I Think You Should Leave.

-

Chris Stirewalt debunks the notion that only Republicans are refusing to be vaccinated at the same time he points out that anti-vaxxine pandering is a losing strategy for the GOP.

-

As the U.S. nears completion of its withdrawal from Afghanistan, Paul Miller reflects on the missteps and strategic mistakes by all the presidents who oversaw the war, from George W. Bush to Joe Biden.

Let Us Know

On the competition and concentration point, do you have a strong preference between chain retailers/restaurants and locally owned, mom-and-pop stores? Is it preferable for economic policy to promote one over the other? How do you decide which kinds of businesses to frequent?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), Harvest Prude (@HarvestPrude), Tripp Grebe (@tripper_grebe), Emma Rogers (@emw_96), Price St. Clair (@PriceStClair1), Jonathan Chew (@JonathanChew19), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.