Breadsticks

CNN just announced that Donald Trump will participate in a televised town hall for the network in New Hampshire next week. It is literally my job to watch this thing, so I will try to do so. But no promises because the question I’m waiting on isn’t going to be answered that night. Instead, I’ll have to wait about two days because that’s when we’ll get the ratings.

If this thing is a ratings boon for CNN, it’s hard to imagine that a bunch of news organizations that are currently laying off employees aren’t going to see a quick way out of their misery. It’s going to be 2015 all over again, when Trump got $2 billion worth of free media attention—remember when there’d be an empty podium on the screen for 45 minutes?—because, to paraphrase the head of one network, he “may not be good for America, but [he’s] damn good for CBS.” But less accidental, less innocent.

And let’s be real. It’s not going to take much. Biden is winning against Trump by 1 to 3 points in the best national polls we have. That’s within the margin of error. And that’s not even taking into account the Electoral College math problem that Democrats still have. Democrats keep acting like they have this thing in the bag because Trump got indicted? Because Trump says crazy stuff? Because Trump?

This town hall could go very, very well for Trump. Not because he sounds presidential or has figured out how to save Social Security or beat China … but because a whole lot of people might tune in.

Lasagna

Zell Miller (D-Georgia), Arlen Specter (R-Pennsylvania), Olympia Snowe (R-Maine), and Heidi Heitkamp (D-North Dakota) are just some of the names that come to mind when I think about the extinction of the political center. The fact that Lisa Murkowski is still a senator is the exception that proves the rule—a famous last name combined with some fancy footwork (a write-in campaign in 2010 and the introduction of ranked choice voting in 2022) has allowed her to survive. Of course, there’s still Susan Collins, but Maine is weird. Mitt Romney has yet to win reelection in Utah. Angus King and Bernie Sanders may be independents, but they’re no centrists. But two names are missing from this list …

And thus we begin our 2024 story of woe with Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema.

West Virginia’s Republican Gov. Jim Justice has formally announced that he will be running for Manchin’s Senate seat this time around. In 2018, Manchin squeaked by, winning by 3 points against state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. For a state where Donald Trump won by 39 points, I suppose we should consider it a political miracle that Manchin has made it this long—like one day’s worth of lamp oil lasting for eight days.

Then again, Republicans aren’t out of the woods yet. Justice was a Republican who ran as a Democrat for governor in 2016. Then he switched back to being a Republican some six months into the job. This might explain why he’s a popular governor in the state, but it also means he isn’t exactly a darling of the conservative right, which sees him as insufficiently committed to their causes. Rep. Alex Mooney has also announced he’ll run for the GOP nomination and has the backing of senators like Ted Cruz and Rand Paul along with a pledge of $10 million in support from the Club for Growth. It’ll be a bruising primary, and maybe while the lions are fighting the buffalo will be able to escape?

But let’s be real. Usually, the lions eat the buffalo. And it’s not just the lions he needs to worry about. Manchin isn’t exactly beloved within his own party. Although it has never made any sense, it has long been a rallying cry within the progressive left to replace Manchin with a “real Democrat” in the Senate. Step one: Democrats nominate a true progressive to run for West Virginia’s Senate seat. Step two: yada yada yada. Step three: Democrats have a secure majority in the Senate. See? They’ve got it all figured out.

But more to our point here, there isn’t some cavalry of Democrats coming to save Joe Manchin. In fact, Josh Seigel reported in Politico this week that Democrats are “losing patience” with Manchin and “tired of the drama” when it comes to Manchin’s criticisms of the Biden administration over things like climate change and green energy.

In the meantime, Manchin hasn’t declared his intentions to run for reelection. Maybe the old buffalo decides not to mess with the lions at all and to run for governor or just retire instead.

Then there’s Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, who in some ways finds herself in a very similar predicament to Manchin and in some ways … not.

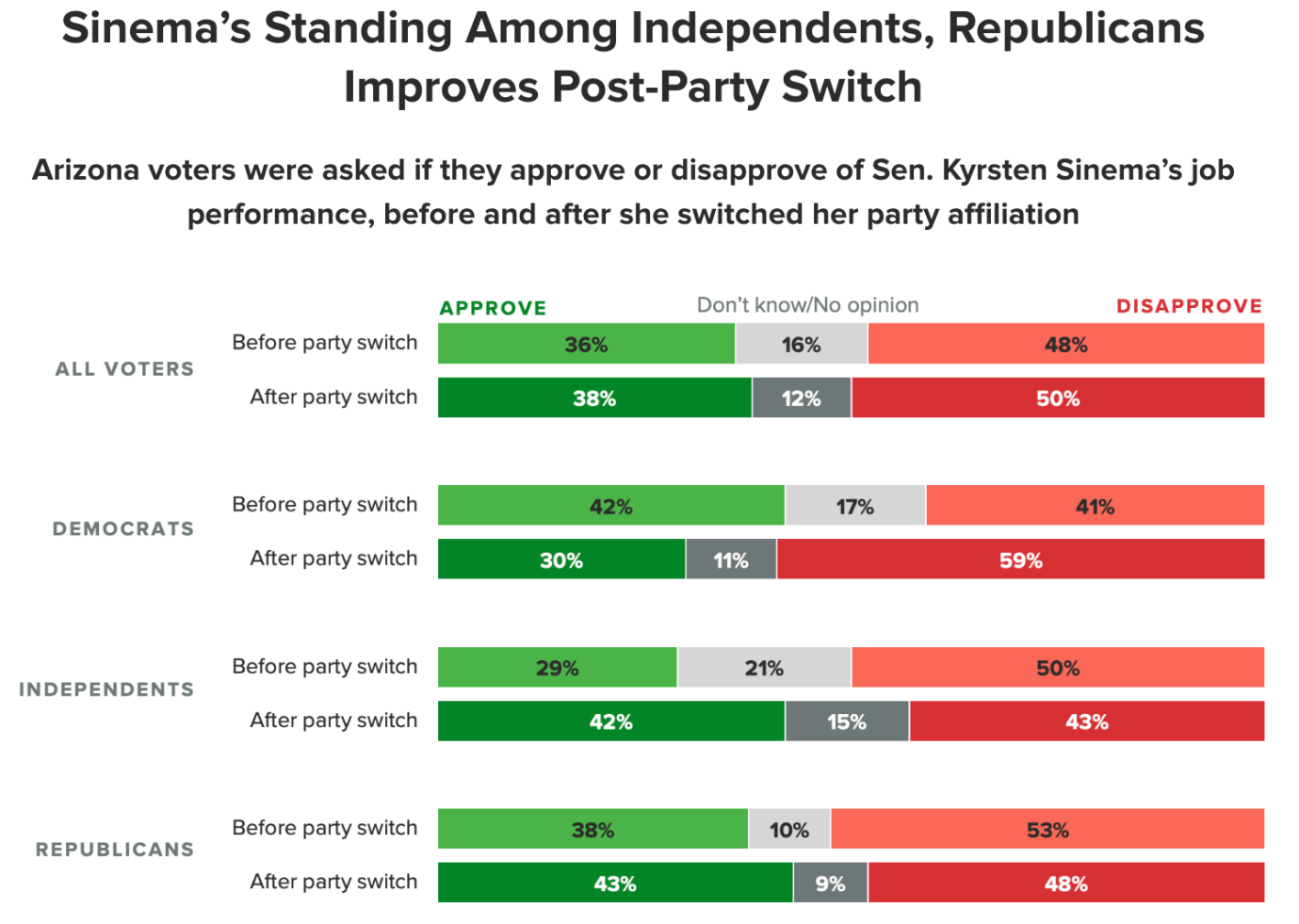

Four months ago, Sinema announced that she was leaving the Democratic Party. It made sense on policy grounds, but it made even more sense because of the politics. Sinema was facing an uphill battle in a Democratic primary against progressive Rep. Ruben Gallego. But Arizona is a first-past-the-post state, meaning Sinema doesn’t need to get 50.1 percent of the vote to win. She just needs to get more votes than the Republican or the Democrat. But that’s no cake walk, as you can see from this survey of Arizona voters:

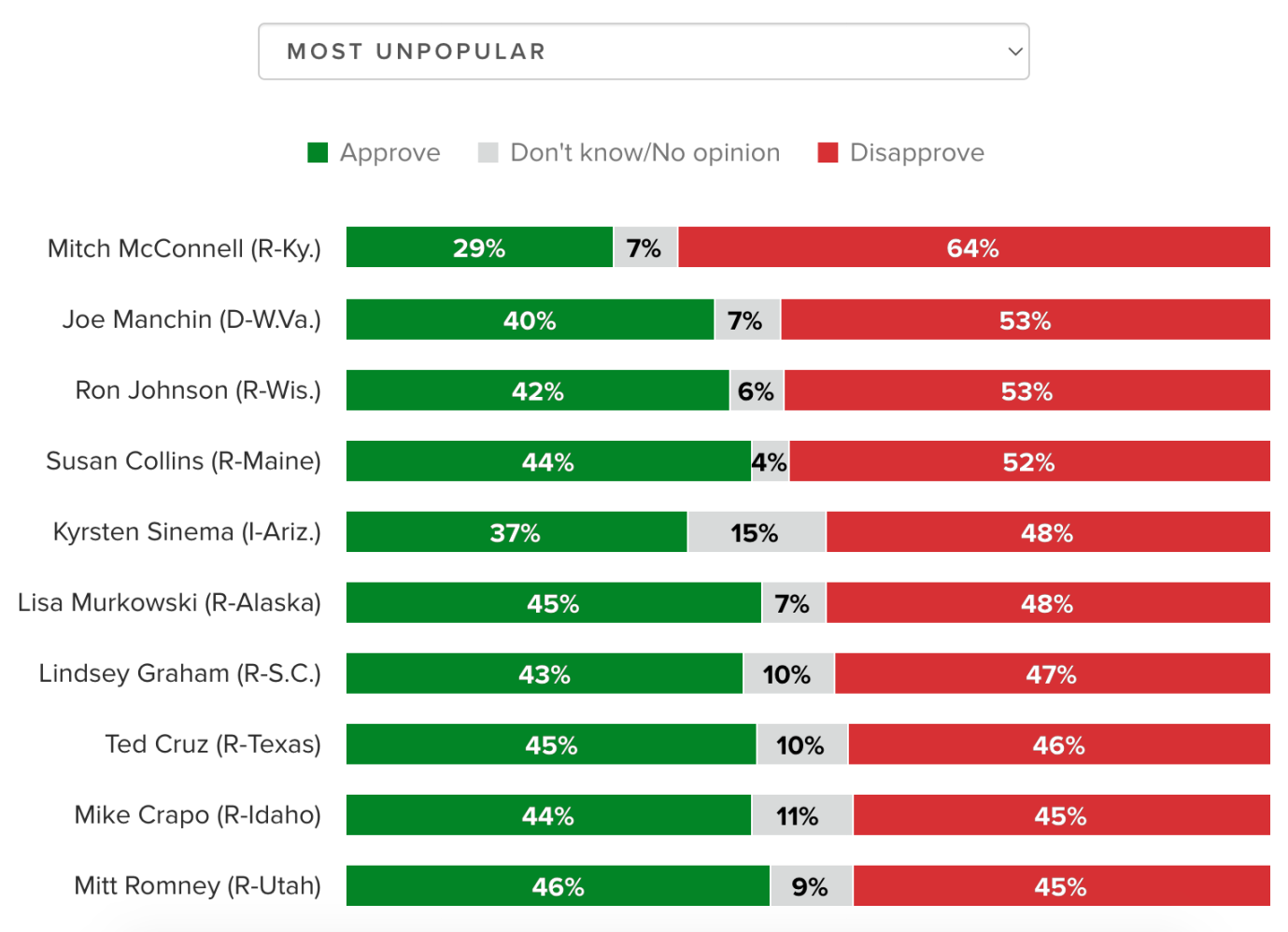

Then again, check out this ranking of the most unpopular senators in their respective states and you may see a trend:

Manchin, Collins, Sinema, Murkowski, and Romney are the senators most likely to break from their own political parties and all of them are in the 10.

Sinema, for her part, has been trying to get the word out that she may not be a good partisan but she’s an effective senator, touting a wide list of legislative accomplishments, including the 2021 infrastructure bill and the 2022 gun safety initiative, that were possible only because she was able to broker deals with both sides.

Of course, neither side particularly liked those pieces of legislation. Too much compromise, too little vanquishing of the enemy. As she told Robert Draper in the New York Times Magazine, “The people who want no bread if they can’t get the entire loaf of bread are people who’ve never been hungry.” The question is whether there are enough hungry people out there. Seems like quite a large chunk are pretty satiated with the negative partisanship they’ve been feasting on regardless of whether their problems ever get solved. As long as there’s someone to blame …and there are plenty of candidates willing to offer blame.

But even there she is an enigma. After his interview, Draper concluded, “Nothing she said in our conversations left me with the impression that she was putting a few final touches on her senatorial legacy on her way out the door to the private sector.” But McKay Coppins, who published a profile at the same time, wrote:

Sinema tells me she hasn’t decided yet whether she’ll seek reelection, but she talks like someone who’s not planning on it. She’s only 46 years old; she has other interests. “I’m not only a senator,” she tells me. “I’m also lots of other things.” I ask if she worries about what lessons will be drawn in Washington if her independent turn leads to the end of her political career.

She pauses and answers with a smirk: “I don’t worry about hypotheticals.”

So what are we to make if two more centrists bite the dust in 2024? Perhaps counterintuitively, I’d argue it is yet another example of the result of ever shrinking and weakening political parties. As more and more people leave the party apparatus, the party has less power and those that remain in the party as county chairs or precinct captains are less representative of their voters. Candidates strike out on their own to raise small dollars from these newly “independent voters” by attacking the parties and the cycle just continues.

The Democratic Party has every interest in keeping Manchin’s seat. After all, it’s either Manchin or a Republican. But nationally, Democratic voters don’t. They would rather be in the minority and blaming Republicans for the country’s ills.

And this isn’t some irrational “cutting of your nose to spite your face” moment. Both sides’ voters want to play “winner take all” politics. No compromise. No negotiations. And they’re both willing to bet they’ll win because they’re increasingly surrounded by people who agree with them and can shut out any voices that disagree. This is the Sinema race. Both sides would be significantly better off with Sinema than with the other party’s Senate nominee. (As a Democrat, would you rather have Sinema or Kari Lake?) But neither side can imagine it will lose. And so Sinema is shown the door.

What replaces healthy, robust political parties isn’t always a descent into chaos. Georgia is a good example. The Georgia GOP—smaller and more extreme—backed a bunch of MAGA challengers to more establishment GOP elected officials in 2022 and lost. The result is that the state party has been even more marginalized since all of these statewide electeds just proved that they didn’t need the state party to win in the first place. The problem is that what replaces the state party—in terms of candidate support like voter data and turnout—is then run by something more fleeting and is usually connected to a single politician that may lose or lose interest over time.

This is what happened to the Democratic National Committee during the Obama years. Obama largely replaced it with his own campaign organization—Obama for America—which turned into Organizing for America. But then Obama left office, OFA shriveled, and when someone unlocked the storage closet, they found the DNC cowering by an old janitor’s pail, blinking like it hadn’t seen the sun in years. Not coincidentally, Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, in case you’d forgotten.

So in the short term, replacing these state parties that have fallen into extremism or just extreme disrepair isn’t all bad. Brian Kemp isn’t a centrist, but he isn’t an extreme partisan, either. The problem is what comes next. After Kemp leaves and takes his data tools and ground game with him, there will be even less of a state party left.

Without a party to protect them, the Manchins and Sinemas will all go extinct—either now or soon—and the result will be fewer people interested in negotiating legislation or representing the interests of their state when it clashes with partisan interests. And our politics, I’d argue, will be worse because of it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.