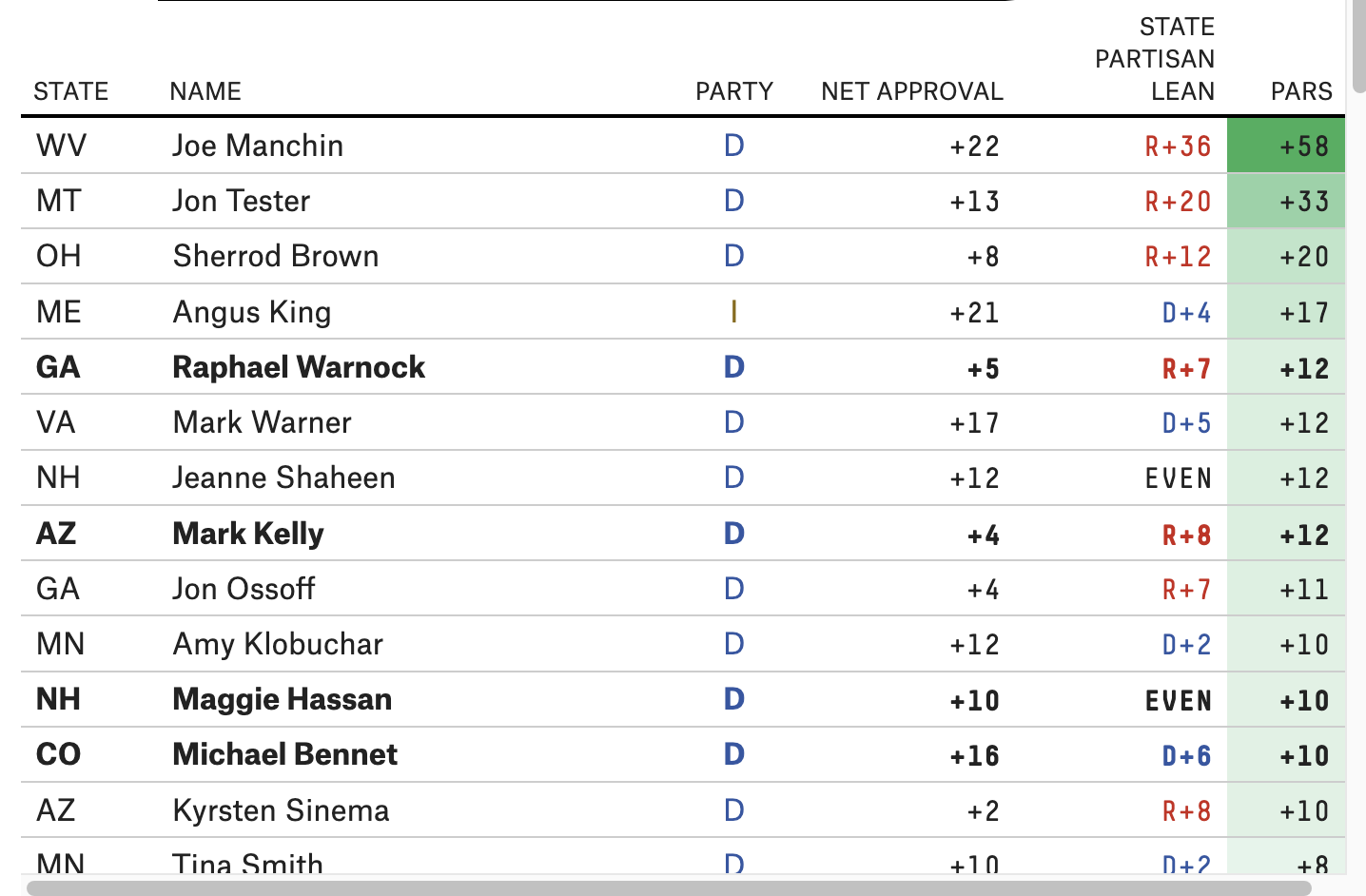

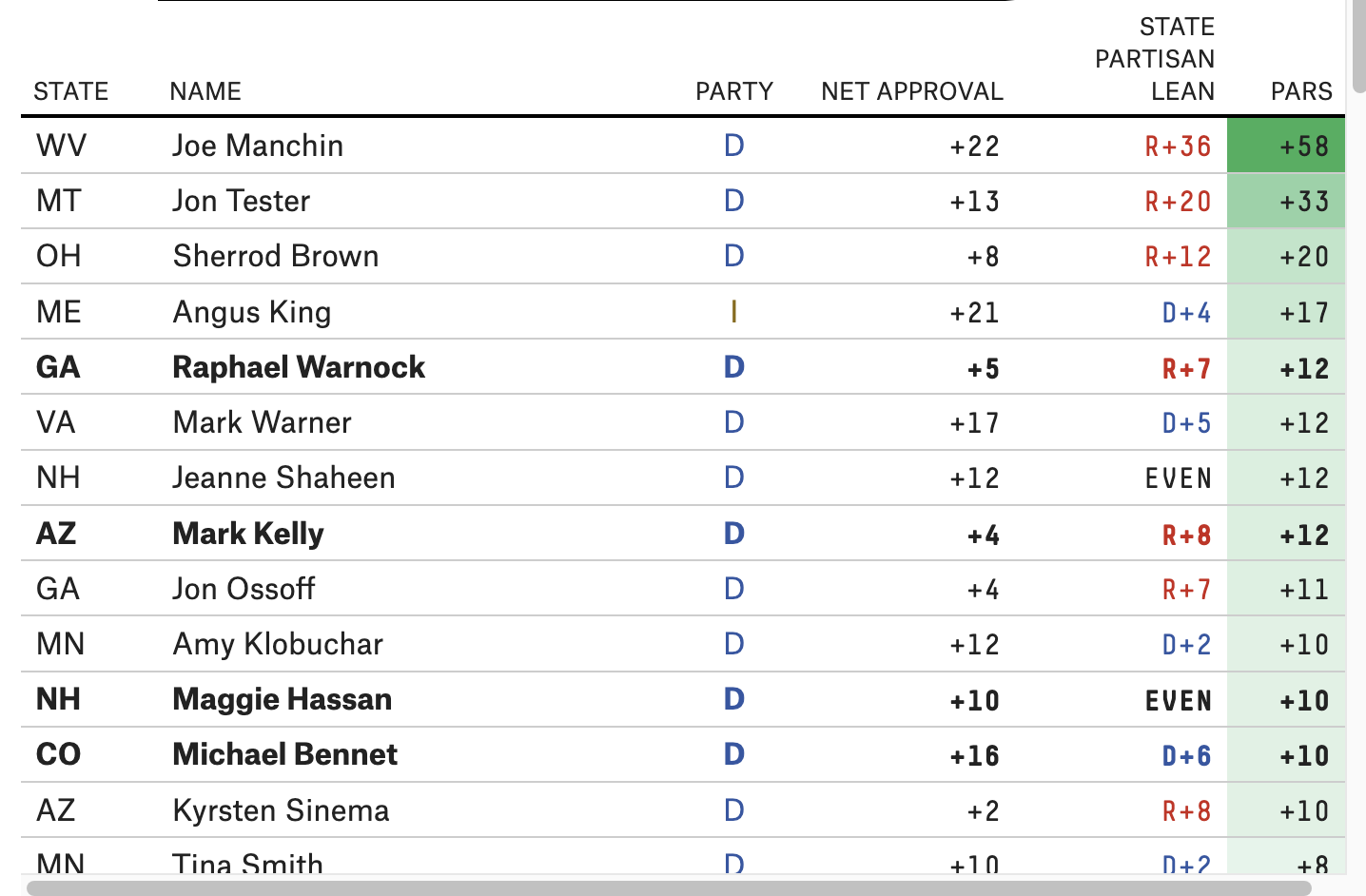

Neat Data Alert

FiveThirtyEight has put together a table to look at “senators with the best and worst statewide brands” by subtracting a state’s partisanship score from a senator’s net approval rating. Here’s the description:

The idea behind these stats is that a 70 percent approval rating for a Democrat in Massachusetts isn’t the same as a 70 percent approval rating for a Democrat in Florida. Because Massachusetts is so blue, that’s no big whoop in the Bay State — but in reddish Florida, it denotes a talented politician with a lot of cross-party appeal.

I bet the results will surprise you … at least a little.

Most Popular

Least Popular

Redistricting Is a Wash

Laser-focused on the new maps, Cook Political Report’s Dave Wasserman finds Republicans are on track to pick up two seats because of redistricting even though there are more “Biden-won” districts overall. Why? He says “the new Biden-won seats are so marginal and so many marginal Trump seats got *a lot* redder.” But the biggest change in the maps can be seen in the “decimation of competitive seats: On the current trajectory, only 33/435 seats will have voted for Trump/Biden by 5 pts or less, down from 51/435 seats today (-35%).”

Speaking of Primaries

Outside groups supporting House Democrats are spending way more cash in this cycle’s primaries than in 2018 or 2020. In the first half of 2018, these races had attracted $5.7 million on TV spending. That number rose to $10.4 million in 2020. This time around? A whopping $25.8 million.

But Democrats are going to lose the majority. Why win the primary if you’re destined to lose the general?

Mark Mellman, a Democratic pollster who is part of one of those outside groups, had an answer for Politico: “[B]ecause the number of competitive districts has declined dramatically, most members are now selected in primaries, so primaries become more important.” Or to put it another way: There’s a whole lot of money to be raised and fewer and fewer effective ways to spend it.

Primaries Are the Problem

While competitive seats are usually a good sign for a healthy democracy, competitive primaries usually mean that the parties—and in this case the Republican Party—is experiencing some kind of realignment. It’s also a pretty good guess that a surge in competitive primaries will push the party further to its base as challengers from the right knock off incumbents or incumbents shift rightward to ward off challengers.

And that brings us to a fun conversation on primary reform. Professor Edward Foley at Ohio State University just published a short little gem in the Washington Post about why our primaries aren’t working.

If the winner has only one-third of the votes, that means two-thirds — twice as many voters — were on the losing side. That’s backward.

And it doesn’t have to be this way. Seven states require candidates to win a majority of primary votes and hold runoffs if they don’t. But holding another election isn’t even necessary if states would follow the lead of Maine, which holds an “instant runoff” by requiring ranked-choice voting in primaries.

…The double use of the plurality-winner rule is a double whammy. First, in the primary, where Duverger’s law has no force, the plurality-winner rule fragments the field, preventing a majority of voters from choosing the candidate who truly is most preferred overall. Then, in the general election, when Duverger’s law takes hold, the plurality-winner rule prevents a candidate who lost a primary — even an irrational primary — from mounting a meaningful independent campaign.

So what is there to do about it? Nick Troiano wrote about Alaska’s solution in The Atlantic last year. (Nick and Ned and I are going to have a whooooole conversation about this next week on The Dispatch Podcast, btw):

Alaska became the latest state to ditch partisan primaries when its voters adopted a sweeping election-reform package on the ballot.

Under the reform, rather than both parties holding separate primary elections, all candidates will instead compete in a single, nonpartisan primary in which all voters can participate and select their preferred candidate. Then the top four finishers will advance to the general election, where voters will have the option to rank them. Whoever earns a majority of votes wins. (If no candidate earns a majority after first choices are counted, the race is decided by an “instant runoff”––whereby the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and voters who ranked that candidate first have their second-place votes counted instead, and so on, until a candidate wins more than 50 percent of the vote.)

With this reform, Alaska became the first state to combine a nonpartisan primary with ranked-choice voting in the general election. Known as “final-four voting,” this system has two major advantages. First, by abolishing party primaries, it eliminates elected leaders’ fear of being “primaried” by a small base of voters within their own party. Second, by abolishing plurality-winner elections and the “spoiler” effect they produce, it levels the playing field for independent and third-party candidates.

“The ultimate purpose is not necessarily to change who wins. It is to change what the winners are incentivized to do,” Katherine Gehl, the founder of the Institute for Political Innovation, explains.

Recount in Pennsylvania: Now The Fun Really Starts

Out of 1.3 million votes cast, about 1,000 votes—exactly 982 as of 2 p.m. on Tuesday—now separate David McCormick and Mehmet Oz. There are still thousands of mail-in and absentee votes outstanding. Those ballots are not part of a recount. They have yet to even be counted at all because Pennsylvania law still doesn’t allow those ballots to be opened until Election Day.

The recount itself will be fairly straightforward. Every county must count its ballots in a different way than how they were initially counted—by hand or a different machine—and report its results no later than June 7.

But that’s not where the action is going to be. This election will be decided by contested absentee ballots.

State law requires absentee voters to sign and date the outside envelope of their ballot, which has led to some number of undated absentee ballots being rejected because they didn’t have the date. But on Friday, a federal court of appeals held that undated Pennsylvania ballots would be counted from a county judicial election last year. Why? Because the ballots had been otherwise time-stamped or dated by the receiving election officials or the post office, making the state’s separate requirement that the voter also date the envelope immaterial as to whether the person was qualified to vote in the election. In short, as long as election officials can confirm that the ballot was received on time, the ballot can’t be discarded just because the voter forgot to date the envelope.

It took less than 90 minutes for the McCormick legal team to email every county, advising them that they were now required to go back and count absentee ballots they had previously discarded for being undated. “We trust that in light of the Third Circuit’s judgment you will advise your respective Boards to count any and all absentee or mail-in ballots that were timely received but were set aside/not counted simply because those ballots lacked a voter-provided date on the outside of the envelope,” said the letter obtained by CNN. Oz’s team put out a statement opposing the idea of going back to count undated ballots.

And, no, this isn’t a principled position from either side. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, McCormick has won “about seven mail votes for every five that Oz has.” Assuming that there were 3,000 undated ballots across the state that were rejected for that reason (out of roughly 90,000 total mail-in ballots), that would allow McCormick to make up about half of his current vote defict.

The same lawyers who just lost in the appeals court now work for Oz, which means they will almost certainly try to get the Supreme Court to step in to stop the undated ballots from being counted. And, of course, there’s all of the other contested absentee ballots—set aside during the initial count for any number of reasons—to fight over. Lawyers fanned out in all 67 counties will be fighting for each and every ballot.

From a political perspective, it will be fascinating to see how the narrative within GOP circles gets shaped. In 2020, the fight over absentee ballots in Pennsylvania pitted Republicans against Democrats, resulting in charges of election rigging and a stolen presidency. But now that it’s two Republicans, the temperature feels quite a bit lower.

“Unfortunately, the McCormick legal team is following the Democrats’ playbook,” said the Oz team in a statement.

The McCormick team responded that they were “glad that Republican primary votes — including active-duty military votes — continue to be counted.”

And now to Audrey with a deep-dive into today’s GOP Senate primary in Alabama.

Alabama Senate Primary Splits the GOP in D.C.

Last spring, Alabama Rep. Mo Brooks was leading the pack in the Republican primary race to succeed retiring GOP Sen. Richard Shelby. Then, for him, came a series of unfortunate events.

His downward trajectory began in August, when a crowd of his supporters booed him for suggesting they ought to move past the 2020 presidential election. Soon his two biggest Republican primary rivals—former Shelby chief of staff Katie Britt and retired Army pilot Mike Durant—caught up to him in the polls and began out-fundraisinghim. Brooks’ waning momentum then quickly became evident to former President Donald Trump, who in late March rescinded his endorsement.

Whether or not these developments will seal Brooks’ fate could become clear in just a few hours, when Alabama voters head to the polls and pick their Republican nominee for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat. Brooks has regained some polling ground in recent days, but the race is still tight and likely headed to a June 21 runoff, as no candidate is likely to surpass the 50 percent threshold required to win Tuesday’s primary. RealClearPolitics’ polling average has Britt with a slight edge over Durant and Brooks, who are neck-and-neck in the race for the second runoff spot.

High-profile Republican lawmakers and organizations look to be just as divided as the electorate. Brooks has the National Rifle Association, the Club for Growth, and GOP Sens. Rand Paul and Ted Cruz in his corner. But he faces stiff competition from Durant, a wealthy businessman and former prisoner of war, and Britt, an attorney and former CEO of the Business Council of Alabama who has secured fundraising supportfrom GOP Sens. Shelby, Mike Crapo, Deb Fischer, Shelley Moore Capito, Jim Inhofe, and Joni Ernst.

Britt and Durant have also benefited from the McConnell-aligned Senate Leadership Fund’s (SLF) $2 million contribution in early April to Alabama’s Future, a Super PAC that has spent the campaign cycle bashing Brooks in television ads.

“I thought that was very wise,” Shelby, Britt’s former boss, said in an interview Thursday of the contribution.

But the move was met with criticism from some Brooks supporters like Ted Cruz, who stumped for Brooks in Alabama this week and who nonetheless insists that Republican leaders should avoid putting a finger on the scale in competitive primary contests. “I always think it’s a mistake when leadership gets involved in primaries, and historically, it’s tended to backfire more often than not,” Cruz said in an interview last week.

Click here to read the rest.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.