Good morning. I hope you’ve had a nice week. It’s been relatively peaceful here in D.C., with both chambers on recess. The Senate is scheduled to return Monday afternoon. The House won’t be back until June 14.

Senate Process Allows Member Input For Once

The Senate will soon vote on the Innovation and Competition Act, a massive bill to invest in research and development and counter the Chinese government.

The legislation, currently more than 2,400 pages long, calls for science funding for a number of U.S. agencies and includes about $50 billion for America’s semiconductor industry. It would also create a new technology directorate at the National Science Foundation to research areas like artificial intelligence. The package incorporates the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s China bill, the Strategic Competition Act, among other items.

Members were expected to approve it last week, but Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer pushed a final vote back amid chaotic delays on the floor as senators jockeyed to include their goals in the measure. The bill will go to the House next, where members there will certainly want to add their own priorities and make changes to the Senate’s version. It’s not clear what a final version of the package will look like, or if it will ultimately be able to pass at all.

But the process the Senate has used to consider the bill has been remarkably open, at least by Senate standards. Senators spent two weeks deliberating as a full chamber after considering the measure in various committees for several months. They’ll spend even more floor time on it next week. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has allowed votes on more than a dozen Republican amendments, as well as several Democratic amendments.

One, brought forward by Nebraska GOP Sen. Ben Sasse, calls for doubling funding for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency over the next five years. “The Chinese Communist Party is currently pouring money into machine learning, AI, and quantum, because they think if they achieve first-mover advantage in cyber, they will ultimately become the world’s preeminent super-power,” Sasse said during floor debate. “DARPA’s job is to make sure that doesn’t happen. We need to make sure that Chairman Xi lies awake at night worrying about his critical infrastructure, his networks, and his vulnerabilities, and DARPA is currently doing that work.”

Senators approved the amendment with a vote of 67-30.

Another amendment, introduced by Iowa Republican Joni Ernst, includes language to block federal funding from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The Wuhan lab is based in the Chinese city where COVID-19 was first detected. It received hundreds of thousands of dollars over several years from National Institutes of Health grants to study bat coronaviruses. Lawmakers have raised alarms at the prospect of a potential lab leak origin behind the deadly pandemic, pushing to prevent government funds from going to the Wuhan lab in the future. Ernst’s amendment passed by voice vote—an expedited process used for uncontroversial proposals.

A related amendment from Kentucky Republican Sen. Rand Paul would block American funding for Chinese government gain-of-function research, which increases a disease’s transmissibility or its ability to infect different species, ostensibly to help understand how future pandemics could emerge. NIH officials have said the terms of the U.S. grant money for the Wuhan lab’s study of bat coronaviruses did not allow for gain-of-function research.

“The origin of the COVID-19 virus is unknown. It has yet to be determined if the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or due to a laboratory accident at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China,” Paul’s office said in a release. “But this pandemic, and the questions of its origin, has exposed the inherent risk of gain-of-function research and never again will taxpayer dollars fund this type of research in China.” Paul’s amendment also passed by voice vote.

Also incorporated into the broader Innovation and Competition Act was a bipartisan measure introduced by the top Republican and top Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee to address a wide range of China-related trade concerns. The amendment would boost U.S. Customs and Border Protection efforts to identify and investigate products made with forced labor—a growing priority as the Chinese government has built a sprawling network of forced labor sites using Uyghurs and other persecuted minority groups. It also establishes a Committee on Trade in Essential Supplies, consisting of key Cabinet secretaries and other officials, to ensure the United States has “reliable access to essential supplies from its trading partners.” Text of the amendment is available here. It passed overwhelmingly, with a vote of 91-4.

If you have too much time on your hands and want to read more, a breakdown of all the amendment votes and floor debate thus far can be found here.

Not all of the amendments that received a vote have passed—several failed. But the fact that the Senate even held votes on them is striking. It’s partly a function of the bill itself: The measure is expected to ultimately advance to the House with bipartisan support, and Senate leaders wanted to allow members to advocate for their priorities.

If you spend any time watching the Senate, you know this is rare. Under now-Minority Leader Mitch McConnell over the past four years, the chamber focused mostly on judicial nominations and almost never brought legislation forward for any kind of robust debate on the floor. When amendments were allowed, it was usually because they were required procedurally in some instances, not out of an earnest desire to allow member feedback.

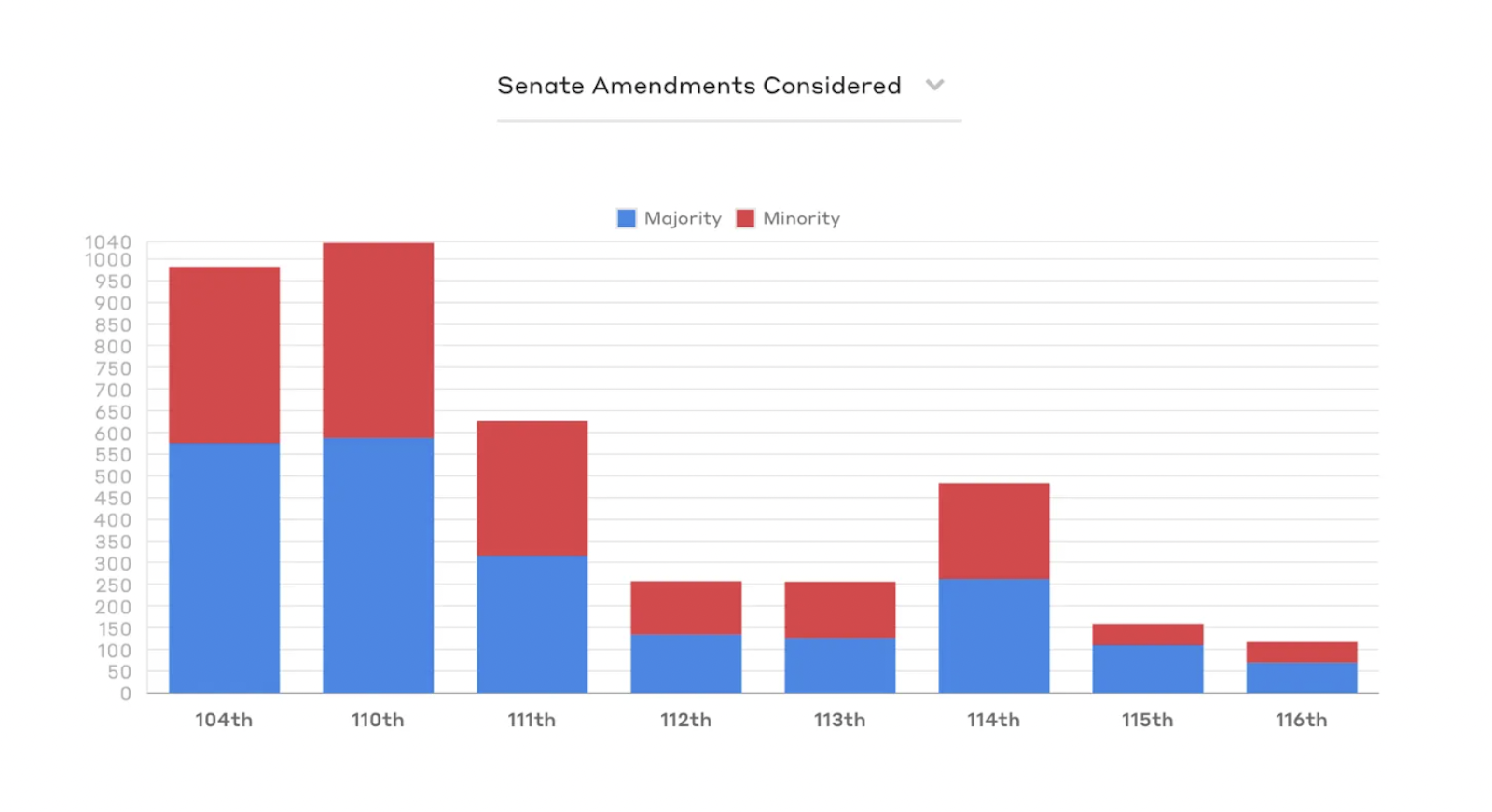

According to a June 2020 analysis by the Bipartisan Policy Center, McConnell’s Senate “considered the fewest amendments—117—of any First Session in recent history” during the first half of the 116th Congress. Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid also strictly managed floor debate and cracked down on amendment opportunities. It’s part of a larger trend of top-down leadership in Congress and reduced input for rank-and-file members. Here’s a graphic from the BPC’s report highlighting the general decline in Senate amendments in recent years:

This isn’t to say that trend is over with. But Schumer’s comparatively open approach to the Innovation and Competition Act this month was a departure from the status quo and has received praise from members of both parties.

“Look, we’ve had bipartisan amendments offered throughout the committee process, bipartisan amendments offered last week, bipartisan amendments offered this week,” said Indiana Republican Sen. Todd Young, who helped author much of the legislation. “I can’t recall when this has happened since I’ve been in the United States Senate.” (Young was elected in 2016.)

And Ohio Republican Sen. Rob Portman said he was happy “to see the Senate working.”

“We’re actually doing a bill on the floor and offering amendments and having debate,” he told reporters.

It’s not a particularly high bar to be impressed with the Senate barely functioning, and it doesn’t guarantee any kind of improved legislative outcome. In fact, the more open process has also elevated parochial interests and added pork to the bill. (See, for example, Washington Sen. Maria Cantwell’s amendment that calls for $10 billion to go to NASA’s lunar lander competition, widely seen as a handout to Blue Origin, which is based in her home state.)

But it’s still nice to see the world’s greatest deliberative body… actually deliberating.

Harris Tasked With Election Reform

My new colleague Harvest Prude, formerly of WORLD Magazine, started at The Dispatch this week! I’m thrilled she’s a part of the team. She took a look at the latest on Democratic voting reform efforts for us in this edition of Uphill:

President Joe Biden added a formidable new task to Vice President Kamala Harris’ portfolio of responsibilities this week: He asked her to get voting reform legislation across the finish line in Congress.

Democrats say passing a sweeping package of voting reforms is necessary to ensure every American has access to the ballot box. Their plan, known as the For the People Act, is a nearly 800-page behemoth that would drastically overhaul voting laws across the country, as well as make changes to the redistricting process, campaign finance laws, and lobbying and ethics standards.

The bill would require states to implement same-day voter registration, expand access to mail-in voting and early voting, and put stricter regulations on how states remove voters from rolls, among other measures.

Republicans have largely opposed the bill. Sen. Roy Blunt, a Missouri Republican, called it a “federal takeover of the election process.” And Tennessee Sen. Bill Hagerty described it as “a power grab” during a recent markup. Much of the right has agreed with that characterization—the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board noted the bill seeks to micromanage states’ election laws “down to the glue on the envelopes.”

But some criticism has also come from the left. State election officials complained to Jessica Huseman of Votebeat, a nonprofit news organization that covers electoral issues, that Democrats failed to consult administrators prior to drafting the bill. If the bill passed, officials said, its stringent requirements, paired with unrealistic timelines for implementation and no guarantee of continued funding, could initially result in chaos. Representatives from the American Civil Liberties Union also wrote in a Washington Postop-ed that some of the bill’s other provisions could have the alarming effect of suppressing political speech and violating privacy.

The legislation passed the House in March with a vote of 220-210, with only one Democrat crossing the aisle to oppose it. In the Senate, every Democrat but Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., is a co-sponsor of the measure. That’s a significant exception—without Manchin’s support, Democrats couldn’t approve H.R. 1 even if they changed the Senate’s 60-vote threshold requirement for passing most bills.

During her time on the Hill, Harris did not exactly have the reputation of a dealmaker. A bipartisanship index by the Lugar Center and Georgetown University ranked Harris 94of 100 senators in the 116th Congress, which spanned 2019-2020. But getting the bill passed in the Senate would be a Herculean task for anyone.

“There’s no voting rights reform in America without the filibuster going away,” Ryan Burge, an associate professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University said. Scrapping the filibuster would also require Manchin’s support. So far, he has been opposed to changing the Senate rules, as has Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema.

The other option, Burge said, is to scrap H.R. 1 and try to pass a narrower bill in its stead. It’s a move some Democrats have argued in recent weeks stands a better chance.

Manchin has voiced support for another voting reform bill which he sees as a more palatable alternative.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, renamed to honor the late civil rights leader Rep. John Lewis, D-GA., would restore the pre-clearance formula, a provision from the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Pre-clearance required certain jurisdictions with a history of race-based discrimination to get federal approval before changing election laws. The Supreme Court scrapped pre-clearance in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision. The court said the formula was outdated and should be revised by Congress. Lawmakers have been unable to come to consensus since.

An updated version of the Voting Rights Act, Manchin told ABC News, should apply the pre-clearance provision to all 50 states and U.S. territories. The proposal has support from many congressional Democrats and at least one Republican, Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. But, as with the For the People Act, it faces a difficult path to passage in the Senate.

“The big picture is that both of these acts … are going to have a very hard time passing,” John Fortier, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, told The Dispatch. “Even if tomorrow you removed the filibuster, there would be other obstacles to getting it done.”

Biden’s decision to place his vice president in charge of shepherding the bill through Congress doesn’t do much to change the political dynamics at play. It does emphasize the administration is gearing up for a showdown on the issue, though. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer announced last week that the chamber will vote in the final week of its June work period on the Senate version of the For the People Act. It’s expected to fail when it comes forward for consideration, but that will only strengthen calls among many Democratic senators and progressive activists to change the Senate rules.

“The work ahead of us is to make voting accessible to all American voters, and to make sure every vote is counted through a free, fair, and transparent process,” Harris said in a release. “This is the work of democracy.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.