Late in the evening of January 31, 2018, an elite team of Israeli spies conducted a secret, high-risk intelligence mission in Iran. The Israelis broke into a seemingly innocuous warehouse in Tehran and, with little time to spare, expertly removed a massive cache of scientific data—a trove of information the Iranians didn’t want anyone to see—without being detected. They absconded with their haul back to Israel. The documents and computer files were part of Iran’s nuclear archive, reports detailing Tehran’s efforts to build and test the components of a nuclear weapon.

The Iranians have long denied that they ever had a nuclear weapons program, telling the world that their nuclear-related work was merely for civilian uses. Some who ought to know better have gone even further, claiming that Iran’s chief political and spiritual ruler issued a religiously binding fatwa that forbids his country from acquiring the world’s deadliest weapons. President Obama endorsed this claim in March 2015, saying: “Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei has issued a fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons, and President Rouhani has said that Iran would never develop a nuclear weapon.”

No one has ever produced a copy of the fatwa in question. And the archive stolen by the Israelis tells a very different story.

The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) has been combing through the Iranian nuclear archive for months. This is the good ISIS, as its employees like to say, and not the evil, marauding jihadis. It is led by David Albright, the physicist and former U.N. weapons inspector. (Full disclosure: The good ISIS has worked with the think tank where I am employed, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.)

Earlier this month, Albright’s ISIS reported on some of the newly translated files. One Farsi table, originally compiled in Microsoft Excel, lists “192 tests related to nuclear weapons development performed at” five test sites from September 2002 to April 2003. The tests were conducted as part of the secretive Project 110. This was part of the larger so-called “Amad Plan,” the name Iran gave its clandestine effort to build and mount nuclear warheads. If Khamenei had truly forbidden nuclear weapons, there never would have been an Amad Plan, or weapon component tests. And yet the Iranian nuclear archive documents extensive work aimed at building such warheads and details of those tests.

Albright’s ISIS also found that Iran’s Project Midan, which was just one part of Project 110, “was responsible for building an underground nuclear weapon test site in the early 2000s.” The Iranians surveyed several possible sites for nuclear testing and apparently concluded that the remote Lut Desert was well-suited. The documentation reviewed by ISIS contains “a detailed geological and hydrological survey” that was conducted in anticipation of possible testing.

Building on these and other revelations, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has sought additional access to suspect sites—to no avail.

“The Agency has identified a number of questions related to possible undeclared nuclear material and nuclear-related activities at three locations that have not been declared by Iran,” IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi said earlier this week. Thus far, Iran has been obstinate.

As my FDD colleague Andrea Stricker points out, the Iranians have justified their defiance by offering a “tendentious interpretation” of the 2015 nuclear deal brokered by the European Union and the Obama administration. Even though President Trump no longer abides by the accord, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Chinese, Europeans, Iranians, Russians, and IAEA still claim to adhere to some of its terms. Stricker explains that, under the terms of the JCPOA, Tehran agreed to help resolve “unanswered questions regarding the possible military dimensions (PMD) of its nuclear activities,” but stonewalled. Even so, the IAEA’s Board of Governors “removed the PMD investigation from the agency’s” own agenda in December 2015. Iran now cites that decision to justify its intransigence, saying it “will not recognize any allegation on past activities and does not consider itself obliged to respond to such allegations.”

In other words, Iran is attempting to use the fact it was never forced to admit to its past activities as a reason it doesn’t have to do so now. This is a bizarrely circular argument, which, as Stricker shows, defies reason. Much evidence has come to light showing why the IAEA, the U.S., and the Europeans should be curious as to what else Iran has hidden and may be still hiding.

There’s much more that can be said about the Iranian nuclear archive stolen by the Israelis, President Obama’s JCPOA, and President Trump’s decision to end America’s participation in it. But one simple point stands out: Iran never came clean concerning the extent of its nuclear weapons activities. And that is a problem for diplomatic efforts to contain Iran’s activities going forward.

The purloined materials reveal aspects of Iran’s nuclear ambitions that were not known when the 2015 JCPOA was negotiated. If Iran can’t be honest about what it was doing under the Amad Plan in the early 2000s, then how can the U.S. and its allies be sure it doesn’t have Amad-style programs now, or in the future? A diplomatic resolution is preferable to military action and certainly an all-out war. But that only underscores the importance of being clear-eyed with respect to the mullahs’ shell game.

But who can the U.S. rely on to help hold the Iranians accountable? The Russians? The Chinese? If anything, they seek to bolster the Iranian regime. Let’s take a closer look at China’s relationship with Iran, in particular.

The partnership between China and Iran.

The relationship between China and Iran dates back centuries, long before the current authoritarian regimes came to power in their respective nations. Iran engages in more trade with China than any other country. China has been a reliable buyer of Iranian oil, though its imports dipped as the Trump administration reimposed sanctions on the Iranian government. The Chinese have been a key source of military hardware for the Iranians in the past. Along with Russia, China is reportedly prepared to sell “new fighter aircraft and tanks when” a military embargo is lifted this year. China has helped the Iranians build its supposedly civilian-only nuclear reactors, and Iran’s ballistic missile program relies on Chinese technology.

After the JCPOA was inked in 2015, Iran had more room to maneuver on the international stage, as sanctions were lifted. The JCPOA granted the Iranian regime some legitimacy. And China sought to take advantage of the more permissive operating environment. As a result, China and Iran struck their own bilateral “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” which called for “upgrad[ing] the level of cooperation of the Armed Forces of the two countries through cooperation mechanisms in the fields of human resource training, fighting terrorism and exchange of information, as well as equipment and technology.”

U.S. accuses Huawei of corporate espionage while working with Iran.

The Iranians have leveraged Chinese technological know-how to crack down on internal dissent. The U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) has accused Huawei, the telecom firm in the middle of America’s “great power competition” with China, of violating various American laws. But some of those same laws deal with U.S. prohibitions against doing business inside Iran.

On February 13, the DoJ filed an expansive, superseding indictment against Huawei. The charges build on earlier allegations, as well as reporting by Reuters and the Wall Street Journal. The DoJ accuses Huawei of employing a complex espionage network to target its corporate competitors and then obstructing justice when this behavior was uncovered. Although Huawei has sought to obfuscate its top-down responsibility for the scheme, blaming various acts on supposedly rogue employees, U.S. prosecutors claim that the company directly incentivized theft.

In 2013, for instance, Huawei allegedly “launched a formal policy instituting a bonus program to reward employees who obtained confidential information from competitors.” Employees would be compensated based on the perceived value of the stolen technologies. After sharing the information on an internal Huawei website, or via encrypted email, a “competition management group” would determine the value of the stolen technology and hand out “monthly bonuses” accordingly. The DoJ says Huawei even disseminated a memorandum outlining this program to employees inside the U.S.

The indictment makes clear that this was just one of the illegal avenues Huawei is accused of pursuing to secure access to competitors’ trade secrets and other intellectual property. Huawei allegedly entered into confidentiality agreements with companies and then violated the terms of those deals in order to use intellectual property for its “own commercial use.” Huawei recruited some of its competitors’ employees to assist in its schemes and also instructed professors to pose as independent third parties. These “proxies” weren’t merely academics conducting research for their universities, but instead cutouts Huawei used to gain access to “nonpublic” technologies it wanted to copy.

Huawei in Iran.

The DoJ’s indictment of Huawei contains significant allegations of Chinese wrongdoing as it relates to business dealings with Iran.

Consider the story of Skycom—an alleged Huawei front company that dodged U.S. and international sanctions while selling telecom equipment to the oppressive Iranian regime. Skycom is registered in Hong Kong but does much of its business in Iran. In 2007, Huawei transferred its shares of Skycom to another, purportedly independent entity, claiming that the formal link between the two had been severed. According to U.S. prosecutors, Huawei “falsely claimed” that Skycom was one of Huawei’s “local business partners in Iran, as opposed to one of” Huawei’s “subsidiaries or affiliates.” In reality, the DoJ says, Skycom was always under Huawei’s control.

Huawei used Skycom to sell U.S.-origin goods, namely telecom equipment, to Iran while also clearing dollars in American banks. The latter practice involves converting funds in a foreign currency to U.S. dollars. According to the DoJ’s latest indictment, the products Huawei sold to Iran included “surveillance technology used to monitor, identify and detain protestors during anti-government demonstrations in Tehran, Iran in or about 2009.”

Those protests were brutally quashed by the Iranian regime. Huawei has denied any knowledge of how the Iranians used its equipment. The U.S. alleges that all the while, however, Huawei misrepresented its business dealings in Iran, as well as in North Korea, as part of a conspiracy to maintain access to American banks.

The U.S. has also accused Wanzhou Meng, Huawei’s chief financial officer, of being a central player in these schemes. Meng was arrested at the Vancouver International Airport in late 2018. A Canadian court is currently weighing whether to extradite her to the U.S., where she would be tried for her alleged role. The Canadian attorney general’s office supports Meng’s extradition, arguing that she engaged in bank fraud by deceiving financial corporations about Huawei’s business dealings in Iran. Meng’s attorneys deny the charges and the court proceedings have increased tensions between China and Canada.

While all of this is going on, the U.S. is also attempting to prevent Huawei and China from dominating the global 5G wireless market. As I outlined in a previous edition of Vital Interests, China’s ascendancy in the 5G world poses both economic and security challenges for the West.

Overlapping threats to American security.

If you listen to America’s national security officials for just a few minutes these days, you will likely hear them say something along the lines of how “complex” threats are as compared to the past. This is a cliché—but it is also true.

Consider again the summary above. While Iran is preventing the IAEA from investigating nuclear weapons work it is suspected of completing nearly two decades ago, China appears to be deepening its military ties with the Iranian regime. The Chinese have also allegedly provided the Iranians with some of the technological tools they’ve used to crack down on internal dissent. This has helped ensure the Iranian regime’s survival, even as the theocracy exports its revolution throughout the Middle East. The Chinese firm Huawei is accused of violating U.S. laws in order to supply Iran with these surveillance tools, while also committing bank fraud to move money around the globe.

As I’ve discussed in previous editions of Vital Interests, “Great Power Competition” (GPC) is all the rage these days in D.C. policymaking circles. There is a temptation within the defense establishment, in particular, to think of threats as an either-or proposition—either the 9/11 wars and jihadism or the growing threat from China and other would-be great powers. There is an inclination to think of GPC as distinct from other, supposedly lesser national security challenges, including the threats posed by rogue states such as Iran and North Korea. But as the story above makes clear, that’s the wrong way to analyze national security threats in the 21st century.

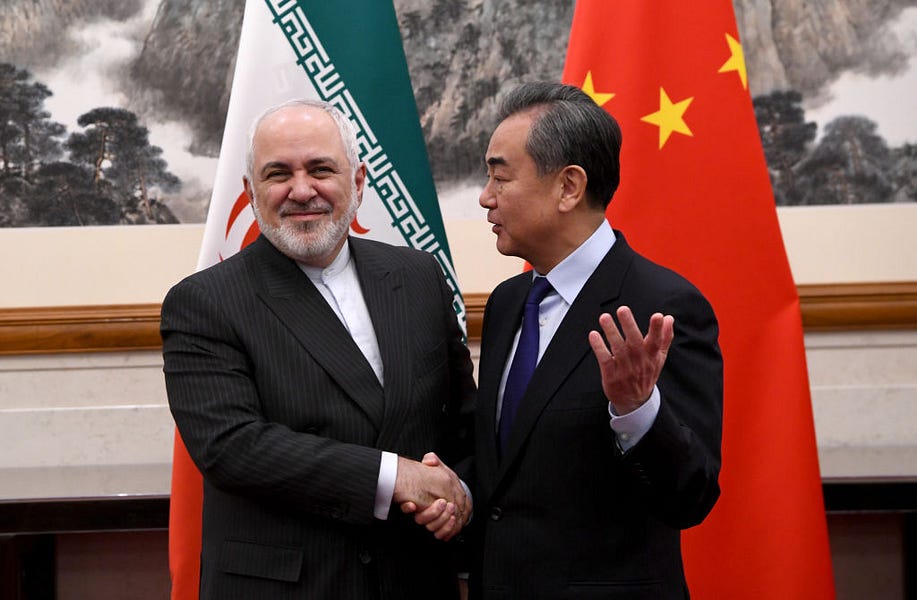

Photograph of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi shaking hands with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif in Beijing, China, by Noel Celis (Pool photographer)/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.