Happy Saturday! I hope yours is going as well as mine. The sun is out, the birds would be chirping if they hadn’t flown south for the winter, and my Wordle streak is perfect. I’m going to try to keep this quick because, like many Americans, I’m getting ready to eat some chicken wings and watch the NFL playoffs.

Maybe I’m feeling chipper because we busted out of COVID jail this week. On January 12, two of our three kids tested positive. (Yes, we’re all vaccinated. It hit before we had a chance to get them boosters.) It was annoying, but they were fine and didn’t even miss that much school. We were off for Martin Luther King Day, and our district preemptively called a “calamity day” for Tuesday to deal with staff shortages. And then they were out of quarantine and back to school.

I’ve written more than once about how lucky we’ve been on the schooling front. We had in-person school throughout the 2020-21 school year (with brief and targeted forays into remote learning when absolutely necessary). This year was as close as you could get to normal, at least until Omicron hit. Our schools send out emails alerting parents of any positive cases, and in the fall we’d go days, sometimes even a week, with no notifications. On January 10, though, we got this note from the high school: “We are writing to let you know that seven 12th-grade students, seven 11th-grade students, fourteen 10th-grade students, nine 9th-grade students, and three staff members have tested positive for COVID-19.” Oof.

The pandemic has left its imprint on every aspect of our lives, obviously, but I don’t know if anything illustrates the sheer frustration of having no great options for how to deal with it two years in than education.

We’ve all heard the horror stories: the big-city districts under the sway of teachers’ unions that never opened last year, the 1 million kids who just didn’t go to kindergarten, the learning loss, the mental health challenges, the uptick in disciplinary issues and outright violence that educators and administrators are witnessing this year. It seemed like things were turning in favor of our kids when Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot tried to stand up to the teachers union in her city. The union voted to go remote instead of coming back in person after the holidays, but instead the district canceled school for five days, until an agreement was reached to get teachers back into classrooms.

But in many cases around the country, schools have had to close, often on short notice, because they simply had too many teachers out, either with COVID itself or in quarantine. There aren’t enough subs. And my Facebook feed is full of pleas from teachers who are working insanely hard, stressed out, and exhausted. They are using planning periods to cover for other teachers, attending to students who are struggling, breaking up fights, and they still having to get lessons in. I sense that many of them are near a breaking point. The ire toward those teachers union leaders who kept millions of kids stuck in Zoom school most of last year is entirely justified, but I can’t help but sympathize with the teachers in classrooms who’ve been through a horrible ordeal. Omicron might be less deadly than previous variants, but hitting as hard as it has in terms of case numbers and the disruption that has generated makes it a real gut punch, the kind that knocks the wind out of you.

We can only hope—as I try to find my way back to the good mood as I was in when I started writing this—that the steep declines we’re seeing in some cities will repeat themselves in areas where Omicron hit later. Until then, thank a teacher (and be nice to the clerks at the grocery store, and throw an extra big tip to the pizza delivery guy). And go Bengals. Who Dey!

This one is personal for me. My parents owned a (literal) mom-and-pop grocery store while I was growing up, and so I’m very familiar with the razor-thin profit margins. Wholesalers kind of expect you to pay for perishable goods such as meat, produce, and dairy, even if you don’t sell them. Refrigeration is expensive. Competition keeps prices low. And yet, in attempting to deflect blame for the ongoing inflation that is contributing to negative wage growth, hitting working class Americans hard and generally making everyone cranky, the Biden administration and leftists like Elizabethe Warren have blamed several industries for being greedy, including grocery stores. In Capitolism (🔒 ), Scott Lincicome takes a rifle to this particular barrel of fish. He points out that there is plenty of competition and that grocers have some of the lowest profit margins of any industry. “The grocery store demagoguery—along with the broader claims that inflation is primarily due to greedy corporations exerting their market power in certain industries—reflects a pretty basic misunderstanding of inflation as a microeconomic (developments in individual markets) phenomenon as opposed to what it actually is—a primarily macroeconomic (determined in the aggregate) one,” he writes.

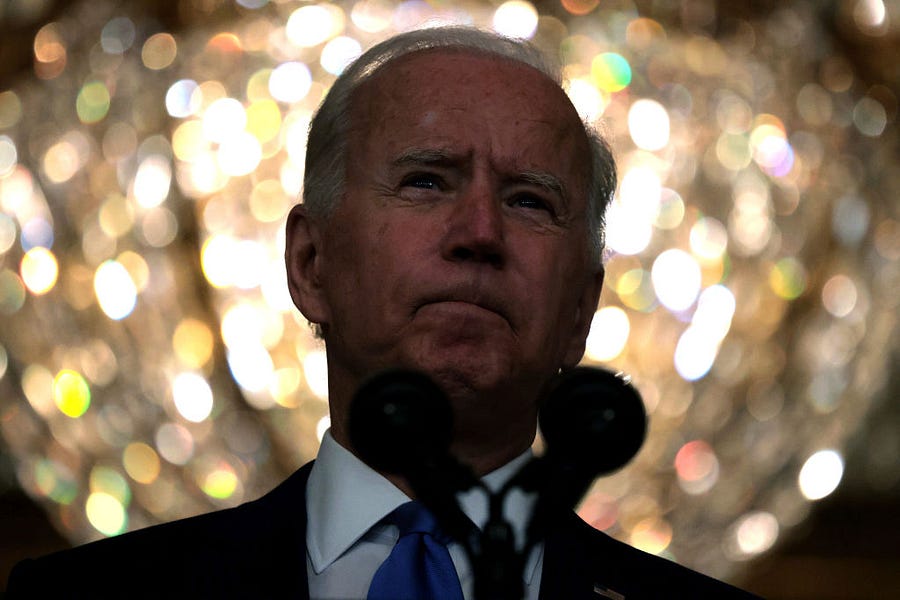

We covered Joe Biden’s incendiary January 11 speech on voting rights legislation—“Do you want to be on the side of Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis?”—pretty critically last week, but we weren’t done. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would update the 1965 Voting Rights Act by reimplementing federal controls over state elections that were struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013. Bob Driscoll takes a look at what the 1965 Voting Rights Act, details how much of it is still the law, and points out that restoring “preclearance”–where states that have had a history of suppressing minority votes need the Justice Department’s approval to any changes in voting laws–could be easily politicized. “None of this is to say that there aren’t issues of legitimate debate on whether some federal election law standards make sense. … But skepticism about or even flat-out opposition to the John Lewis Voting Rights Act is hardly tantamount to opposition to the Voting Rights Act, opposition to civil rights, or being a segregationist,” he writes.

Andrew covered the March for Life on Friday with a piece we posted this morning. He describes the crowd as smaller—perhaps because of the bad weather in the South and the challenges presented by the pandemic surge and resulting restrictions–but enthusiastic. And one big thing was on everyone’s mind: the potential end of Roe v. Wade, as the Supreme Court heard arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, a direct challenge to Roe, in December. “What might life look like in a post-Roe America?,” he asks. “Some marchers, leery of raising their own expectations, said that’s a bridge to be crossed when we come to it. Others made it clear they realize that, although Roe has been the primary target of the pro-life movement for nearly half a century, its dissolution doesn’t mean the movement’s war is won.”

No one wants a war with Russia over Ukraine. Which is why it’s so important, David argues in his Tuesday French Press (🔒 ), for America to do what it can to keep Russia from re-invading. It’s not just in the interest of Ukraine. It’s in America’s interest too. He points out that such aggression threatens the global order and that “what happens in Europe rarely stays in Europe.” But perhaps his most important point is a direct counter to arguments from those such as Tucker Carlson and Green Greenwald (talk about strange bedfellows) that support Putin’s claim that the U.S. and its NATO allies are the true aggressors. “History teaches us that Russia’s desire to dominate the nations along its border extends when Russia’s border extends,” he writes. “If Russia swallows Ukraine up to, say, the Dnieper River, that doesn’t render Russia ‘secure.’ It just pushes its zone of insecurity and its area of desired domination that much farther west. It places more free nations under threat, and as those free nations fall under threat, it increases pressure on their treaty allies to make their security guarantees more concrete, including through forward deployments. And that ratchets up tensions all the more. “

And now for the best of the rest:

-

Danielle Pletka surveys the various escalating national security threats we are facing right now—from Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran—and argues that the disastrous Afghanistan withdrawal has emboldened our foes. (Relatedly, Matthew Kroenigand review the administration’s handling of relations with dictators in its first year.)

-

Speaking of Afghanistan … While the country is not technically in the Middle East, our failure there has affected how the U.S. is viewed in the region. Jonathan Schanzer writes that “neo-isolationist trends in American politics … [raise] troubling questions about the future of the U.S. commitment to the order it established in the Middle East.”

-

Frederick Hess grades the Biden administration’s higher education policy one year in, and points out that, like a student who increases the font size to make a term paper long enough, the president cut corners by turning to executive orders while his agenda went nowhere in Congress.

-

Continuing on our theme of reviewing the Biden administration’s first year, Brian Riedl tallies up all the receipts. Even though Build Back Better failed, the president managed to spend a heckuva lot of money. (He has some words for the GOP, too.)

-

Let’s hear it for the pods: In her interview with Steve and Sarah on The Dispatch Podcast, former Democratic Sen. Heidi Heitkamp has some advice for Joe Biden. He should take it. On Advisory Opinions, David and Sarah discuss the “Maskgate” controversy prompted by a (disputed) NPR story claiming that Justice Neil Gorsuch declined to wear a mask at Supreme Court arguments this week and so forced Justice Sonia Sotomayor to work from home. And on The Remnant, Jonah reflects on Biden’s first year in office.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.