America’s newspaper of record, the New York Times, revised history in real time this week, and very recent history at that. In a news article on the attitudes of voters regarding President Trump and the Black Lives Matter movement, reporters Astead Herndon and Dionne Searcey wrote:

A survey of battleground states critical to November’s election largely mirrored the national results. Fifty-four percent of voters in those states said the way the criminal justice system treats black Americans was a bigger problem than the incidents of rioting seen during some demonstrations. Just 37 percent said rioting was a bigger problem, though Mr. Trump and his allies have tried to discredit the protests by focusing on some isolated incidents of violence.

However, based on the New York Times’s own reporting alone, that characterization of the prevalence of violence isn’t remotely accurate. In fact, in the space of three weeks, the Times went from “the devastation in Manhattan was unlike anything New York had seen since the blackout of 1977” and “widespread violence and vandalism breaking out in American cities” to “some isolated incidents of violence.” Further examples abound.

The same article that noted the “devastation in Manhattan” reported that “police said that more than 400 people were arrested in New York overnight on Sunday, mostly for looting and burglary.” Another article said that even with 8,000 officers deployed, the police were “unable to contain the bands of looters or to stop them from smashing windows and breaking into stores,” even with another 700 arrests.

The number of arrests is not the only indication of how widespread the looting quickly became. A Times article on the impact of the looting said “CVS said that more than 250 locations across 21 states faced varying levels of damage from protest activity,” and “Target … said over the weekend that about 200 stores would close or have shorter hours as a result of protests and looting.” Soon after, Target stopped reporting the growing number of stores affected.

Other early Times coverage also noted that the violence was not just confined to a few locales: “Businesses across the country suffered destruction over the weekend as protesters unleashed their anger over the death of George Floyd on commercial enterprises — from the offices of major multinational corporations and banks to family-owned restaurants and bars.”

Yet another article reported: “Major chain stores, mom-and-pop groceries, statehouses and police precincts have sustained damage. Police cars have been burned across the country. Mayors of multiple cities have cited damage in the millions of dollars[.]”

By any measure, the protests against police misconduct during the weeks since the death of George Floyd at the hands of, or more precisely, the knee of the Minneapolis police, have been massive. Some events have been peaceful, with some cities, such as Detroit, experiencing little to no violence related to, or taking advantage of, the protests.

Further, as the Times article recounts, the response of President Trump has been on balance confrontational and divisive rather than measured and unifying. But instead of entrusting readers with unencumbered facts, the New York Times now seems more intent on creating a narrative of how it wishes events had played out rather than the reality on the ground. (Neither of the reporters nor the Times‘s communications representative responded to a request for comment.)

The recent episode involving Tom Cotton’s now infamous Times op-ed resulted in a revolt by Times staffers, a good deal of introspection by the Times, a shakeup at the highest levels, and a 325 word editor’s note on the op-ed expressing regret for its publication and called the editing process that led to it “rushed and flawed.” But an editing process that would allow “some isolated incidents of violence” to slip into a straight news piece on the violence of the past month is a process that is similarly rushed and flawed, helping to paint a picture wildly at odds with the newspaper’s own previous reporting—and reality.

Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” If the New York Times intends to apply the Moynihan standard to future op-eds, certainly it’s appropriate to apply it to its own news reports as well.

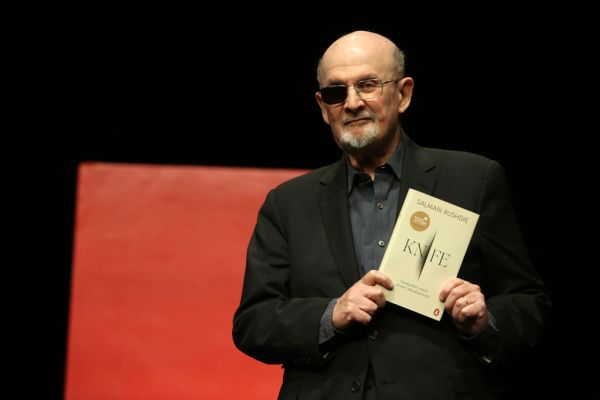

Photograph by Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.