Former Vice President Mike Pence intrigued many by his recent statement that he would consider appearing before the January 6 committee. The possibility of Pence’s testimony renews the importance of examining the role President Donald Trump and his attorney John Eastman envisioned for Pence in their election scheme.

In December of 2020 and the early days of January 2021, as Donald Trump was looking for ways to invalidate the election, Eastman drafted two memos that sought to make the case that Pence could overturn the election himself by rejecting the slates of electors from seven states that had been won by Biden, giving Donald Trump enough votes to prevail in the Electoral College.

In a normal presidential election year, the process for counting the electoral votes is straightforward: On January 6, following the election, a joint session of Congress fulfills its requirements under the 12th Amendment in the following manner:

The President of the Senate (Vice President) shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.

By this constitutional mechanism, Congress accepts the ballots provided by the individual states, certifies them, and declares the election of the President and Vice President. But according to memos purportedly written by Eastman, the vice president, in his role as president of the Senate, has the unilateral ability to assess the votes and reject those deemed invalid. The more detailed of the Eastman memos argues:

There is very solid legal authority, and historical precedent, for the view that the President of the Senate does the counting, including the resolution of disputed electoral votes (as Adams and Jefferson did while Vice President, regarding their own election as President), and all the Members of Congress can do is watch. … VP Pence opens the ballots, determines on his own which is valid, asserting that the authority to make that determination under the 12th Amendment and the Adams and Jefferson precedents, is his alone.

The memo then lays out the scenarios by which this initial rejection of allegedly faulty votes could lead to a Trump victory. Each scenario is dependent on the theory that Pence had the authority to unilaterally assess and reject the votes of the electors. This perceived authority gave hope to Trump and his supporters on January 6. It was Pence’s refusal to exercise this alleged authority that led to Trump’s denunciation of Pence, his fall from grace among Trump supporters, and the chants of “hang Mike Pence” from the January 6 mob. All of this was the natural consequence of flawed, outcome-based reasoning presented to Trump in the Eastman memos. Neither strict construction nor historical analysis validate Eastman’s claims.

In the election of 1876, the nation experienced its greatest test of the electoral system when rampant fraud, intimidation, and violence against black voters in Democrat-controlled Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina called the validity of their slate of electors into question. Two months after Election Day, the result was still disputed. Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote, but Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had a narrow path to victory should each disputed elector go his way. Adding to the confusion was the disqualification of a Hayes elector in Oregon, whom the Democratic governor subsequently replaced with a Tilden supporter.

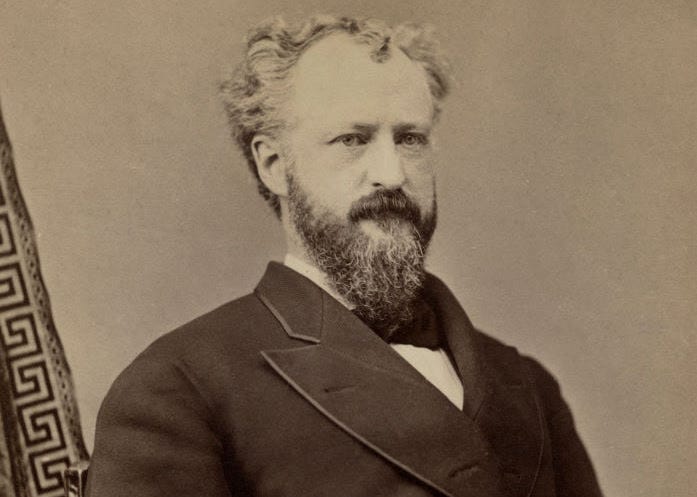

Republican Ulysses S. Grant, the hero of the Civil War and exiting president, appealed to Roscoe Conkling, the charismatic political boss and Republican senator from New York, for a solution to the quagmire. Sensing danger of civil unrest, even renewed civil war in the air, the two men agreed on the need for an independent election commission appointed by Congress to rule on the disputed electors. Conkling, renowned for his mastery of oratory, took to the Senate floor in favor of the commission. In a speech that runs to 48 pages printed, delivered over two days, Conkling argued fervently against the small minority of voices pressing the Republican president of the Senate to act unilaterally to resolve the election in favor of the Republican Hayes.

Conkling’s argument was four-pronged, relying on: 1) the text of the Constitution and the settled rules of construction; 2) historical precedents; 3) the opinions of great American thinkers; and 4) the practice of the preceding 87 years under the Constitution. He did not dispute that the counting of votes was more than a ceremonial process, and that the authority to count the votes implied the authority to reject erroneous votes. But he did firmly dispute that such a power resided with the vice president.

Starting with the explicit language of the Constitution, he highlighted the role it provides the vice president as president of the Senate:

The president of the Senate is clearly the person to whom the electors are to transmit, in a seal packet, the certificate of their own appointment, and of the ballots they cast—he is clearly the person who is to keep these packets and keep them inviolate, till the day comes when the law says that Congress shall be in session, the certificates shall be opened, the votes counted, and the persons who shall fill the office of president and vice president ascertained and declared agreeably to the Constitution.

Why explicitly give the function of opening the certificates to the president of the Senate? Conkling explained that an early draft of the Constitution placed the power to elect the president in case of a tie with the Senate, a power that was ultimately vested in the House of Representatives. “An incident, and a natural incident of this arrangement,” Conkling explained, “was to commit the custody of the certificates to the presiding officer of the body which was to elect the president if none was found to have been chose.” Thus, argued Conkling, it was unreasonable to believe that the authors of the Constitution, having ultimately rejected the Senate’s power to choose the president in case of a tie, would vest the presiding officer of that same body, the vice president, with the power to unilaterally choose the president in case of invalid ballots.

Returning to the strict reading of the vice president’s role, the opening of all certificates, Conkling declares:

“The president of the Senate shall ‘open all the certificates.’ There is no room for construction here. This is a plain grant of power to do a certain simple thing, and a direction to do it. Now the language changes. ‘The president of the Senate’ is dropped; he disappears, and nowhere re-appears: ‘And the votes shall then be counted.’ That is, a count of the votes shall then take place; a count of the votes shall then be had…By whom? By him?

[I]f the president of the Senate was to open and count, if it was to be one act at one time in one place by one person, all parts of the act must of necessity be ‘then,’ must they not? Why bring in the word ‘then?’ But why change the current of the sentence, and why use twice as many words as were necessary or natural, when the effect of doing so would be to bewilder, if not mislead, the reader? The Constitution is terse, sententious, a model of comprehensive brevity. You scan it in vain for another instance of a phrase so loose and needlessly wordy, if indeed the intent was to say that the person who was to open the certificates should also count.”

After emphasizing the importance of a plain reading of the constitutional text, Conkling reviewed the history of the provision, searching for a draft whose language might signal the intent to vest power in the vice president. “Was it ever, in all the scrutiny which those words underwent, proposed to use such words as would commit the power compressed into the word ‘count’ to the president of the Senate? No, sir.” Therefore, there is no explicit charge to the vice president to count the votes.

Conkling then turned to the assertion that the vice president’s charge to open the certificates implies the right to assess the validity of the votes, a claim he also found wanting:

The argument seems to be first, that because the president of the Senate is the custodian of the certificates and directed to open them, it may be implied that he has power afterward to count the votes they contain; and then from that implied power it may be implied that he had the power to determine what shall be counted; and then from this second implied power may be implied the power to decide and affirm the effect of the count he has made, and of the votes he has held valid.

In addressing this argument, Conkling provided a clear explanation of the doctrine of “implied power” under the Constitution. “When power is given to do a thing, permission is implied to employ the means to do it.” This is a well-established element of our constitutional system. Could it be that the power to open the certificates from the various states implies the power to rule on them? Certainly not, said Conkling.

Implication operates in favor of the right to do an act minor to and involved in something beyond which is expressly authorized. Power to do a limited and defined thing, does not ordinarily work powers to do a greater thing—the greater contains the less, not the less the greater. … Power to do a ministerial act does not imply power to act judicially.

In other words, we cannot imply or infer a greater power from a lesser power. Granting your neighbor the right to enter your property does not grant him a right to possess the property. However, if you sell the neighbor a right of possession, he naturally receives the lesser right to enter the property, and to grant or reject requests from others to enter it.

Applying this basic logic to the 12th Amendment, Conkling described the vice president as nothing more than a custodian of papers, a custodian of great importance, granted, but one whose constitutional role ends upon opening of the sealed certificates:

Authority to act as custodian of papers, does not confer license to exercise transcendent powers of sovereignty. … The certificates must be opened before their contents can be examined or passed upon–they must be opened before counting their contents can begin: how then can power to judge and ascertain afterwards, be inferred from power to produce and open beforehand? How can the latter be incident to the former? Breaking the seals is merely prefatory to a wholly different proceeding.

Conkling applies the analogy of a court clerk, who, having received documents into his possession and functioning as their custodian, must present them for review before the court. Does the clerk’s role as custodian give him the ultimate power to rule on the substance of the documents before the court? No. Of course not. How then could the president of the Senate, being vested with only expressed custodial power over the certificates, be inferred the power to rule on their efficacy?

Turning to the historical argument, which Eastman so boldly relies on, Conkling found no support for the vice president’s power to assess the votes.

Eastman expressly relies on the experience of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson as precedents for the president of the Senate ruling on disputes affecting his own election as president or vice president. However, after examining the congressional record, Conkling found no such precedent.

He notes that on February 3, 1797, with Vice President Adams presiding as its president, the Senate formed a committee to “ascertain and report the mode in which the electoral vote should be examined.” Conkling described this as a “bald usurpation, if the President of the Senate had the right to examine.” Subsequently, when Adams was asked to fulfill his role, he declared, “In obedience to the Constitution and law of the United States and to the commands of both Houses of Congress, expressed in their resolution passed at the present session, I now declare John Adams is elected President” If the right to ascertain the president and vice president resided with Adams himself, what commands did he need to obey?

The slim factual basis for Eastman’s erroneous interpretation derives from legitimate concerns regarding the method employed by Vermont in certifying its votes. The electors had been appointed by the state, but not under specific state legislation, as required under the Constitution. Thus, there was some trepidation about their validity as to form. However, no one objected to the counting of the votes from Vermont, Jefferson being unwilling to press the matter given the clear intent of Vermont to vote for Adams. Having no objection, Adams did not “rule” on the matter, and with no ruling or consideration, came no precedent.

Likewise, Jefferson counted votes from Georgia that were flawed as to form in his favor in the tied election of 1800, but only as a result of no objections. Congress, seeing no objections, tabulated Georgia’s votes for the Virginian. Once again: no objection, no precedent. In fact, Jefferson supported a resolution governing “how” Congress should tabulate the vote, never considering “whether” Congress had such a power.

On the other hand, historical precedent against the Eastman-Trump theory can be found in the election of 1805, when Aaron Burr charged the joint session of Congress in the following manner, “’You will now proceed gentlemen,’ said he, ‘to count the votes as the Constitution and laws direct.” Burr, not one to shy away from self-aggrandizement, deferred to Congress as the constitutional engine of the vote count.

In 1817, a representative from New York challenged the votes from the recently admitted state of Indiana. “What occurred?” asked Conkling rhetorically, “Did the president of the Senate assume to determine? No, sir. The houses separated to decide whether the votes should be counted or not. … Nobody suggested that the President of the Senate had anything in the world to do with it.”

In 1824, then-Sen. Martin van Buren championed a bill delineating a new process by which the two houses of Congress would conduct the counting of the vote moving forward. This bill did not create a new power for Congress but simply delineated the means to exercise that power. It provided no mechanism for the president of the Senate to do the same unilaterally.

Although the bill died due to poor legislative timing, Conkling emphasized how it passed through the hands of Rep. Daniel Webster of Massachusetts and his Law Committee without a “dot of an i or the cross of a t” changed. Webster remains one of the most revered lawyers and defenders of the Constitution to have served in Congress. If the Constitution empowered the vice president with unilateral power to reject the votes, how could such a stalwart of the law, a strict constructionist, let such an error go unremarked and unchallenged in his committee? The answer is simple; he saw nothing wrong with it. The vice president had no such power.

Conkling next considered a resolution passed by Congress in 1865 and presented to President Abraham Lincoln for signature. The resolution touched on the validity of votes that might be presented by Confederate states for the election of the president and vice president, the Confederacy being in its death throes. The resolution declared that no votes from states in rebellion would be counted. President Lincoln, acknowledging that Congress was acting pursuant to the 12th Amendment, declared the two houses of Congress “have complete power to exclude from counting all electoral votes deemed by them to be illegal.” He further extolled, “[I]t is not competent for the Executive to defeat or obstruct that power by a veto. … He disclaims all right of the Executive to interfere in any way in the matter of canvassing or counting the electoral votes.” Thus, spoke the man who had boldly pressed the prerogative of the executive to the extreme in defense of the Union. Was he now shying away from the use of executive power against the rebellion? No, in the matter of the election, there was no executive power at his disposal.

Throughout his two-day speech, the first day being cut short by exhaustion brought about by a severe cold, Conkling illustrated that history was against the Eastman-Trump theory even in 1877. “[E]very count from the beginning has been conducted and controlled by the two Houses, that from first to last tellers appointed by the Houses have enumerated, and that the president of the Senate has never even enumerated the votes.”

History, reason, practice, and the Constitution all align in common cause against Eastman and President Trump. Conkling’s speech illustrates this many times over, too many times to summarize here. The weight of history and practice have only increased over the subsequent 145 years. Conkling’s 1971 biographer, David M. Jordan, describes the speech as Roscoe Conkling’s finest moment. A fierce partisan, a political boss of the most egregious order, a proponent of the political spoils system, and a beneficiary of the post-war dominance of the Republican Party, he seemed to rise to the occasion.

Congress ultimately approved the bipartisan electoral commission and the commission ruled in Hayes’ favor on all disputed electors. While the actions of the commission are criticized to this day, the nation survived the electoral crisis of 1876 thanks to the principled stand taken by Conkling to preserve the constitutional order. The nation survived again in 2021 when Vice President Pence took a similar stand. There are those, undaunted by the failure of the Eastman-Trump scheme who would surrender the protections of our Constitution for the expediency of power. Should we hear from Vice President Pence when the select committee investigating January 6 reconvenes, let us remember the words of Sen. Conkling, which vindicate the vice president’s actions that day:

Do reason and the fitness of things suggest that our fathers meant the President of the Senate should be the one man, even if there were to be one man, to decide whether alleged irregularity or fraud should vitiate the vote of a State, and turn the seal in the choice of Chief Magistrate (President) of the Republic?

We are asked to believe that our fathers intended to make one individual the sole judge in his own case, though divine law and civilized jurisprudence had declared since the morning of time that no man should ever be judge in his own case, not even if other judges sat with him.

Yet we are asked to believe that our fathers, trained men, the victims of abuses under other systems, and profoundly jealous as their words and acts show they were of the weakness, the ambition, and the greed of man, deposited absolute power with a single individual to decide for himself and for the nation whether he should mount the highest pinnacle of American, if not of human ambition.

They imposed no disability, or even interval of probation, on this one judge, but straightway they made him the party also with their own hands! Such a judge we are invited to believe, they so entrenched, that in the presence of the whole nation, because in law every State and every citizen is present (through Congress), he might by fraud or error undo the nation’s will and the nation’s right, and the nation must bow mute and helpless before wrong and usurpation.

If the Constitution ordains this one-man power, let every man bow to it, mystery though it be. But I do not so read, I cannot so read. The canons of construction, the letter and spirit of the Constitution, reason, all revolt against a conclusion so puerile and so perilous. Prudence points with warning hand to a day when parties in the Senate may be reversed, and when new majorities may set up presiding officers to wield licentious power under a baneful precedent established now.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.