In March 1787, Founding Father Benjamin Rush already had his mind on the corrosive effects of “cancel culture.”

“Ignominy is universally acknowledged to be a worse punishment than death,” wrote Rush in “An Enquiry Into the Effects of Public Punishments Upon Criminals, and Upon Society.”

“It would seem strange, that ignominy should ever have been adopted, as a milder punishment than death, did we not know, that the human mind seldom arrives at truth upon any subject, till it has first reached the extremity of error,” he wrote.

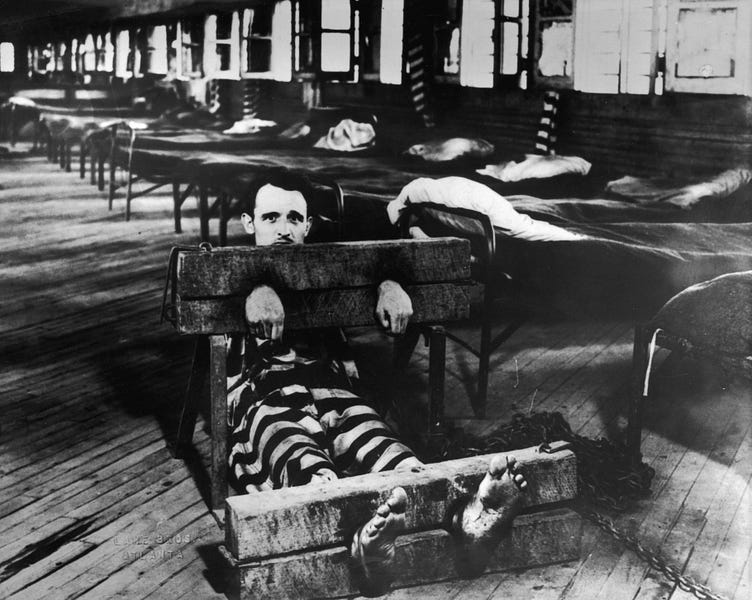

Rush, a Declaration of Independence signatory, was talking primarily about punishments subjecting individuals to public embarrassment—being held in stocks in a town square, public labor, etc. But he could just as easily be talking about modern day cancel culture—subjecting individuals who speak in violation of woke scripture to public harassment.

Rush, however, was discussing the powers of the state—whether local governments should hold people up for ridicule after they have been found guilty of a crime. He would no doubt be aghast at a structure of public shaming in which the judge and jury convicting people would simply be others in the community capriciously deciding what transgressions had occurred. Take, for example, what happened when 150 or so prominent individuals of diverse ideologies and ethnicities criticized the “intolerant climate” of the increasingly illiberal American society in an open letter published by Harper’s Magazine.

The letter—signed by luminaries such as J.K. Rowling, Malcolm Gladwell, Noam Chomsky, and Salman Rushdie—noted recent episodes of public shaming, such as when a New York Times editor lost his job for publishing an op-ed by a sitting U.S. Senator, a researcher was fired for sending around a peer-reviewed academic study, and numerous professors have found themselves the subject of investigations after reading literature aloud in class.

“While we have come to expect this on the radical right, censoriousness is also spreading more widely in our culture,” the authors wrote, citing, “an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty.”

The letter itself is a fairly anodyne statement in favor of free expression. The response to the letter was anything but.

Immediately, far-left social justice advocates moved to argue that simply signing a letter in favor of open dialogue was a cancel-able offense. If you agree on the value of speech with, say, Rowling, who believes transgender women do not share the same experiences as biological women, the “power dynamic police” are quick to arrest you for “denying” transgender personhood.

On Friday a group of journalists and academics released their own open letter—titled “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate”—which called the Harper’s appeal “an attempt to control and derail the ongoing debate about who gets to have a platform” and criticized its signatories for their “stubbornness to let go of the elitism that still pervades the media industry.”

Ironically, in a letter that posits the non-existence of cancel culture, several individuals refused to sign their actual names to the letter, fearing … you guessed it … public reprisal.

In fact, the criticism to the original letter came so fast that two women—author Jennifer Finney Boylan and historian Kerri Greenidge—apologized for signing it, effectively canceling themselves before the mob could do so.

The lesson, of course, is that some individuals don’t believe certain opinions are worthy of a public platform. By making the case that someone’s words—or merely their signature on a letter in proximity to other “problematic” thinkers—makes them “less safe,” they can equate those words with “violence.”

But more importantly, the lesson of both the Harper’s letter and its response is that cancel culture is here to stay.

As Benjamin Rush’s writings tell us, “cancel culture” is older than America itself. Retaining order by inflicting shame upon others is an inalterable human impulse—the only difference now is who decides what “order” is and who gets to do the shaming.

In Rush’s time, sullying the reputation of another private citizen required buying a newspaper, wearing a sandwich board around town, or nailing flyers in the town square. The Mark Zuckerberg of the time was the guy who invented cupping his hands around his mouth so he could yell louder on a street corner.

But social media allows these town-square yellers to find one another and gang up on people they deem unworthy. And even though it may be a few thousand people banding together to signal their virtue, that is often enough to scare employers into firing, for instance, a worker caught on camera having a bad day at Costco or even a man goaded into unwittingly flashing an alleged “white power” sign.

Not only is this desire to feel better by ruining peoples’ lives through ignominy an inalterable biological pleasure for some of the more extremely online justice warriors, there is nothing anyone can do about it.

This isn’t, strictly speaking, a “free speech” issue worthy of high-minded speeches about the First Amendment. The cycle is familiar: People say constitutionally protected things on social media that run afoul of progressive conventions, and the mobs similarly execute their free speech rights by calling for their cancelation. There can be no “Stop Calling for People to be Fired Act of 2020”—the legislative remedy for cancel culture is nonexistent.

The only antidote for mob rule is for employers to begin behaving like adults and stop capitulating to a few loud voices online that count their victories in personal ruination. The cancelers will always be with us, and they will always seek to serve as America’s human resources department.

Like coronavirus, America will have to live with them for a long time, and the only vaccine is public disinterest.

Photograph by American Stock/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.