Life-affirming festive films are as fundamental to Christmas as warm fires and emetic portions of food. But Eyes Wide Shut, famed principally for its most lurid scenes, may not seem to fit in with It’s a Wonderful Life, The Bishop’s Wife, and other familiar favorites. Still, if—as painfully unoriginal people are so fond of remarking—Die Hard is a Christmas movie that requires annual viewing, then so is Stanley Kubrick’s magnificent, misunderstood final work from 1999. Rich in thematic relevance and artistic flourishes, Eyes Wide Shut offers perfect companionship for a dark winter’s night.

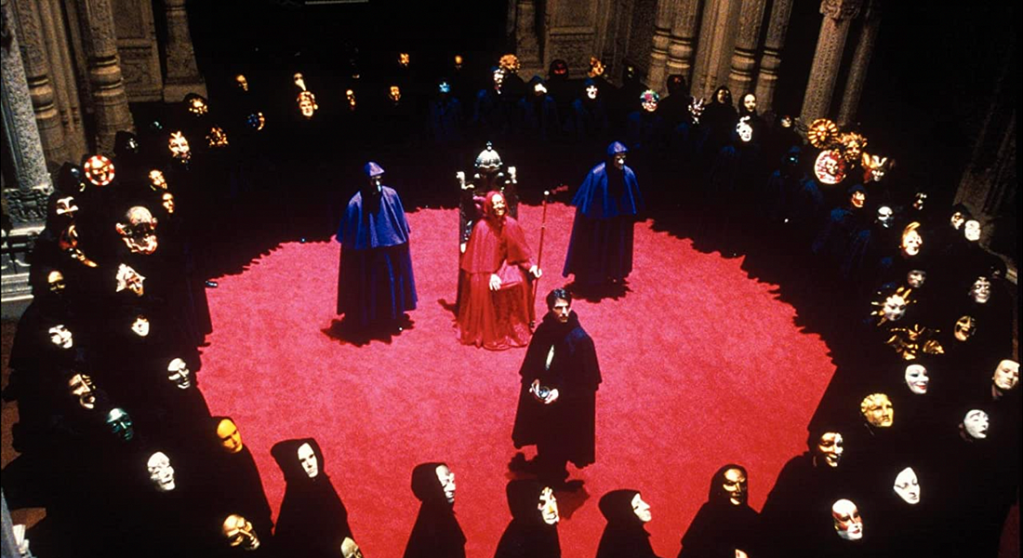

Marketed as a lubricious erotic thriller in the mold of Basic Instinct, the film was met with an almost vitriolic reception upon its release when audiences instead discovered a hypnotic meditation on ideas of class, love, and reality. Tom Cruise stars as Bill Harford, an affluent Manhattan doctor whose life appears idyllic. His apartment is lavish, his wife, Alice (Nicole Kidman), is beautiful and refined, and his young daughter seems poised for a successful future. One evening, however, Alice shatters Bill’s complacency when she confesses to having contemplated an affair with another man. Devastated, he ventures out into the night, moving through a series of surreal encounters that test his fidelity and probe his psychology. His voyage culminates at a remote mansion, where he interrupts a secret society’s ritualistic gathering. The next day, struggling to understand what he experienced, Bill retraces his steps.

Bill’s adventure takes place at Christmastime, and the holiday itself is as lively a character as anyone he meets on his odyssey. Although cults and adultery may not usually be indicative of the season, the same cannot be said of the wreaths, presents, and songs that surface throughout, or the trees and multicolor lights that permeate almost every scene. When Bill and Alice attend a party at the palatial home of their friend, Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack, who delivers a memorable and uncharacteristically coarse performance), white lights flow from the ceiling to the floor like radiant waterfalls. Likewise, when Bill visits a prostitute’s modest apartment, even she has managed to decorate with a tree that bathes both of them in a pinkish glow. Kubrick creates a magical holiday atmosphere, evocative of yet removed from quotidian life.

Eyes Wide Shut’s Yuletide New York is an illusory imagining of the real city. The streets and neon-lit buildings are suitably grand, but distant from actual Manhattan geography, as if Kubrick had designed them from a corroded memory. Curiously given the season, religious iconography is absent. There are no nativity displays to be seen, carols are not sung, and the characters either express no religious sentiments or openly disregard biblical moral standards. Bill is not contemptible. He is an ordinary man grappling with ordinary male anxieties; a comfortable protagonist who feels trapped by his own introverted tendencies. But throughout his journey, he nonetheless considers indulging in various sordid liaisons, purely for the sake of scoring some internal victory over his wife. All the while, he is indifferent toward the actions of his wealthier peers, who are capable of living brazenly hedonistic lives as a result of their elite status. Bill enjoys the authority his social position affords him, but his exploits reveal how far he truly is from the top of the hierarchy of end-of-century America. Eyes Wide Shut can easily be taken as a commentary on marriage and commitment, but its real concerns are power and decadence.

Granted, the film hardly sounds like a vessel of Christmas cheer in such a description. But like any festive classic, its ultimate message is one of renewal. Bill emerges from his adventures with his eyes wrenched open to both the intricacies of his marriage and the influence of those who tower above him. He can greet the new year with a strengthened connection to his wife and an unclouded view of the world that he must raise his daughter to navigate, although certain things will always be beyond his control.

Aspects of the film may irritate some. Kubrick grants equal weight to inane actions, banal exchanges, and significant plot occurrences, while his determination to mesmerize the viewer requires events to unfold at a glacial pace. The dialogue is mannered and humorless, as Kubrick wanted to avoid the romantic verbal duels common to screwball comedies where characters speak exclusively in witticisms. But altering these decisions would diminish Eyes Wide Shut. If Cruise and Kidman had the repartee of Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn, their relationship would not be universal in the tensions and intimacies that characterize it. Interactions between the characters are both dreamlike in their stiffness and realistic in their lack of coordination. The result is the film’s distinct tone: real enough to affect and surreal enough to transfix.

Eyes Wide Shut could be called a masterpiece for many conventional reasons. The camerawork is majestic, the use of music is sublime, the set design is sumptuous, and the performances are so captivating that almost every actor involved could have been justly nominated for an Academy Award. But there is an ineffable beauty to it, a deeper profundity that is difficult to articulate and has left me obsessed since my first viewing. Perhaps the best explanation is that, like the finest works of art (Hamlet, Don Giovanni, The Brothers Karamazov), Eyes Wide Shut is so perfectly constructed, so layered and penetrating in its observations, that it can be interpreted in an endless number of ways. No two viewings will provide the same experience, and no amount of discussion will solve all of its mysteries. It is a work of true humanity that must be seen, and there’s no better time for that than Christmas.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.