Editor’s Note: This is the third of five installments of a story documenting the creation and passage of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The first installment is available here. The second is here, the fourth is available here, and the fifth is here. The story is based on more than 21 hours of interviews with more than two dozen people involved, including lawmakers, staff, and human rights advocates. An audio version of the story is available here. Dispatch members can download a PDF of the full report here.

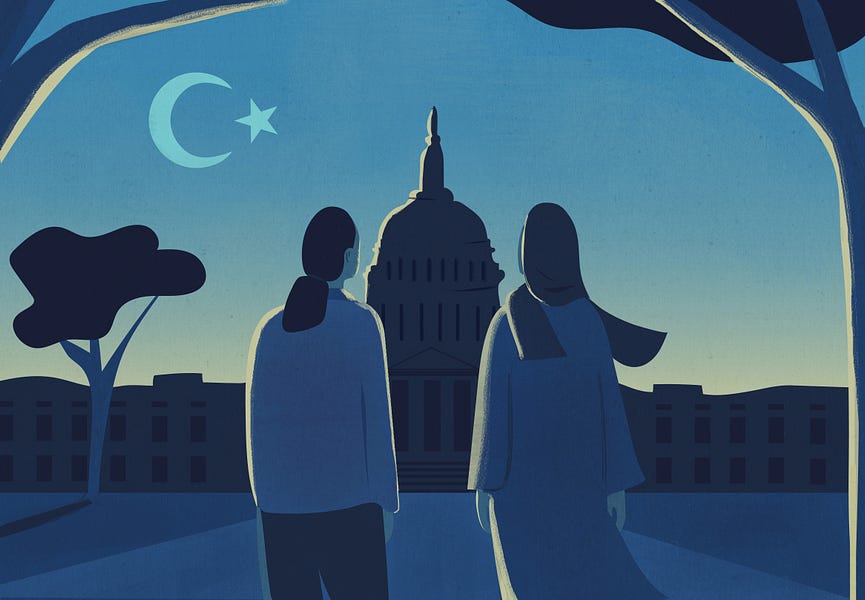

4. The Outside Game

Rushan Abbas’ sister is imprisoned by the Chinese government.

Her disappearance came less than a week after Rushan, an American citizen who grew up in Xinjiang, spoke at a 2018 think tank panel in Washington, D.C., about the genocide. For more than two years, her family did not receive any answers about where she had gone. Only in 2020 did the Chinese government confirm Gulshan Abbas, a 60-year-old retired medical doctor, had been arrested on ludicrous charges of terrorism.

Gulshan isn’t the only one. On Rushan’s husband’s side of the family, two dozen family members have disappeared since 2017, with no word from them since.

Instead of being silenced by the Chinese government’s intimidation, Abbas has become even more vocal about the atrocities in Xinjiang. If she does not spend each day working to build public awareness of the genocide or urging policymakers to help, she says, she cannot sleep at night.

It’s difficult to sleep even when she does.

“I lay down in the bed and I think about her, where she is,” Abbas says. “What is she eating? What is she doing? If she’s still alive. What kinds of torture she’s facing. Whose T-shirt she’s making.”

Abbas, who established the nonprofit Campaign for Uyghurs in 2017, has worked alongside other leading Uyghur advocates and human rights organizations to share the facts of forced labor in Xinjiang and to pressure businesses to prioritize human rights and leave the region.

Abbas was among the activists, including labor rights organizations and human rights groups, who were indispensable in building public support for the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act and in helping get it passed into law.

Abbas spoke at the March 2020 event for the introduction of the forced labor bill. Despite facing powerful opponents, she had faith the measure could become law.

“I did hope and believe the bill was going to pass, because I believe humanity is not dead yet,” she says. “There are so many people still fighting.”

The Campaign for Uyghurs is one of about 60 human rights groups and other organizations that have formed the Coalition to End Uyghur Forced Labor. After forming in the summer of 2020, the coalition advocated for the forced labor bill every step of the way. The groups called on companies to move their supply chains out of Xinjiang, lobbied congressional offices to back the legislation, and provided counterarguments to the business community’s attempts to weaken the bill.

It’s a critical point in understanding the law: It came about only after immense pressure from witnesses of the atrocities in Xinjiang and their allies. People harmed directly by China’s genocide—who have family members still in the camps, who were tortured in the camps, who were raped in the camps, who have been stalked and intimidated by Chinese agents abroad, who have watched their religious and cultural sites razed—are on the front lines calling for the western world to end its complicity.

“When we speak, we try to put the human face to this genocide and forced labor and China’s crimes,” Abbas says of Uyghur advocates. “But what the coalition was doing was working very hard with the evidence. So many different organizations coming together, working together, made us feel that we are not alone. We have all these people backing us up and trying hard to do the right thing.”

One of the coalition’s top goals was to win over more cosponsors for the bill. While it had bipartisan support, many offices simply weren’t aware of the issue or hadn’t spent time looking into it. Different organizations divided up offices to contact. They emailed with congressional staffers to answer questions about the legislation, and they set up calls to talk about it.

Uyghur groups, including the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) and the Uyghur American Association, organized dozens of online meetings between congressional staff and Uyghurs living in the United States. Louisa Greve, director of global advocacy at UHRP, helped prepare people for the calls and participated in many of them. She was struck by how offices with widely different views on most political matters were unified about backing this bill.

“I remember thinking, wow. There’s really no difference between Republicans and Democrats,” she says.

But what stands out to her most in hindsight were staff members’ reactions to the Uyghurs’ stories of suffering. She says Hill staffers were overwhelmingly interested in helping. Advocates were able to track the support they were winning as they watched the bills’ cosponsors grow.

“It was a huge source of hope every time there was a new cosponsor, because it was one step closer to having the American market not be complicit in these atrocity crimes,” Greve says.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium, says he remembers feeling the bill was “probably a long shot” when it was first introduced, because “the legislation imposes very substantial obligations on large corporations that have a lot of political clout.”

“It is vanishingly rare,” he says, “for the U.S. Congress to pass legislation related to global trade that imposes substantial obligations on corporations selling goods in the U.S.”

Nova, who is also involved in the Coalition to End Uyghur Forced Labor, says proponents of the bill had far less power to influence lawmakers than corporate opponents did. That’s why the coalition worked to heighten public awareness of the scope of forced labor in western markets.

“What was happening was a strong effort to create greater and greater awareness in Congress and among the broader public—and awareness on the part of Congress of the growing awareness of the broader public—so as to create strong momentum in favor of action,” he says.

With its awareness campaign, the coalition created an environment in which it would be difficult for lawmakers not to respond to the prevalence of Uyghur forced labor products.

Advocates also pushed back on business groups that opposed the bill.

In one striking letter from the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, former commission president Russell Moore directly challenged Tom Donohue, who was president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce at the time.

Moore urged him to contemplate the eternal consequences of standing in the way of efforts to root out forced labor.

“I know you do not want to be a part of any complicity in the bloodthirsty human rights violations of the Chinese Communist Party,” Moore wrote. “But, sadly, for far too long, many corporations have done just that. Human beings are made in the image of God and are more significant than temporal gains or losses on a spreadsheet.”

“I would urge you to consider the sort of ultimate moral accountability that will come before a God who counts human life as precious and as infinitely more than units of economic output,” he added. “I strongly urge you to reconsider your opposition to these bills.”

Chelsea Patterson Sobolik, director of policy at the ERLC, says that in follow-up conversations, the ERLC made the case that businesses and governments do have the tools they need to find and address forced labor.

“That doesn’t mean it’s easy, but they do have the levers and tools available to them,” she says.

“Passing this bill, unfortunately, isn’t a no-brainer to every policy maker,” she says. “At the end of the day, I would just say advocacy really does matter.”

Even as lawmakers from both parties embraced the plan, the bill faced an uphill climb. One advocate remembers worrying the legislation was stuck at many points along the way, as congressional aides received pushback from corporations and offices negotiated new versions. The coalition collaborated to try to figure out why it was stuck and how to clear the path. Once one muddy spot was cleared up, another would soon come along.

Abbas has a similar description: She likens it to when her son was born 100 days premature, weighing only 1 pound, 13 ounces. He struggled to put on weight when he was in an incubator in the newborn intensive unit.

“He would gain a little bit of weight, and then he would drop the water weight,” she says. “It was just extremely frustrating.”

She says the process of passing the bill in the United States underscored the need to connect the genocide to people’s daily lives.

“This is about you,” she says. “Your conscience as a human being. Because the conscience of humanity is being tested here. Are we going to fail it? Or are we going to pass it?”

Greve says the lesson for human rights advocates, as they attempt to win support for similar action in other countries, is persistence.

Persistence became even more essential for the American bill after a new president took office in January 2021. When Senators Rubio and Merkley reintroduced their revised version of the bill that month, advocates hoped it could move quickly. It didn’t.

“It was terribly disappointing to see no action on a bill that was clearly the will of Congress,” Greve says.

But with a new administration came new concerns about the bill.

Senior Biden officials worried banning products from Xinjiang would hurt the United States’ climate goals. Nearly half of the world’s polysilicon came from Xinjiang in 2020; the solar industry was overly reliant on the region for key components. Cutting off Xinjiang imports could undermine the availability of solar panels and hike costs in a year that had already seen skyrocketing polysilicon prices.

Biden officials weren’t particularly transparent about their internal debate about the bill. When repeatedly pressed on the issue by RealClearPolitics White House correspondent Philip Wegmann—who reported extensively on the forced labor bill and the Biden team’s deliberations over climate priorities throughout 2021—former White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki avoided answering questions about the administration’s stance on the legislation. She later denied that officials had been pushing against it. Yet news reports and conversations behind the scenes increasingly made it clear that an influential sect in the White House was objecting to the legislation.

Over the summer of 2021, human rights leaders noticed a disturbing trend in rhetoric from the president and senior officials: The administration showed no urgency to act on forced labor in Xinjiang.

The bill’s supporters started to raise alarms. They were especially worried about climate envoy John Kerry. Chinese officials were refusing to meaningfully negotiate on climate goals as long as the United States was taking unrelated human rights actions against the Chinese government. It came to a head in September, when Kerry returned from a trip to China and made a series of lukewarm comments about the genocide and forced labor in Xinjiang.

During Kerry’s trip to China that month, he was at pains to emphasize cooperation was still possible in areas of agreement.

“My response to them was, ‘Hey, look, climate is not ideological, it’s not partisan, it’s not a geostrategic weapon or tool, and it’s certainly not, you know, day-to-day politics,’” Kerry told reporters afterward. He said he told the Chinese he would share their complaints with President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

In another interview after the trip, when asked about trade-offs between climate and human rights, Kerry told Bloomberg News’s David Westin that “life is always full of tough choices and the relationship between nations.”

Those remarks quickly drew condemnation from Republican lawmakers.

It wasn’t the first time Kerry had given a halfhearted response when pressed on the genocide.

During a May 2021 House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, Kerry acknowledged that Uyghur forced labor in solar supply chains was a problem, but he also told GOP Rep. Chris Smith that combating slave labor in China is “not my lane.”

In late September, Rubio and Smith wrote a letter to Biden raising concerns about Kerry’s position and urging the administration to support the forced labor bill. The letter, without any Democratic signatures, was among the first indications that a previously nonpartisan effort was going to turn into something more caustic. Between July and September, as the bill languished, Republican lawmakers and aides concluded it was time to go on the offense: The White House and Democratic leaders would have to be pressured (and, at times, shamed) into advancing the legislation.

“We are concerned that Mr. Kerry is downplaying the genocide precisely because he intends to import solar panels that are produced using forced labor in the PRC to the United States in order to meet your administration’s climate goals,” Rubio and Smith wrote. “This appears to be the reason Mr. Kerry seeks to desensitize others to this immoral and unnecessary tradeoff by mischaracterizing it as simply a ‘tough choice.’”

The State Department declined requests to speak with Kerry for this story.

In the aftermath of Kerry’s comments, Uyghur groups also renewed their calls for the White House to take a firm approach to the atrocities in Xinjiang. Julie Millsap, then working with the Campaign for Uyghurs, told the Associated Press in September that Uyghur advocates were “horrified at what we observe” in the Biden administration’s weighing of climate and human rights.

The interview came as Millsap was in London preparing to testify during the second meeting of the independent Uyghur Tribunal, which had gathered to examine evidence of the Chinese government’s genocide in Xinjiang.

“This was what was happening in the rest of the world, and then to see that was what the United States was saying publicly while something like that was happening abroad, that sticks out in my mind,” she says.

At the start of the Biden administration, Millsap says, Uyghur advocates had a lot of optimism about Biden. He had publicly called the treatment of Uyghurs genocide during the 2020 presidential campaign, months before the Trump State Department officially adopted that language. But after Biden took office, advocates received tepid responses about the forced labor bill and realized the administration’s China policy wasn’t coherent. By the time Kerry was ramping up his conversations with Chinese officials ahead of the November 2021 climate summit in Glasgow, Uyghur advocates were “very alarmed,” Millsap remembers.

“What John Kerry had to say about everything was kind of confirmation of our worst fears, just in terms of hearing a lot of lack of clarity, lack of clear policy, and then to see that the only thing that they had sort of nailed down was this approach on climate change was incredibly jarring.”

**Clarification, June 23, 2022: The Dispatch has updated this story to reflect the reporting Philip Wegmann did on the issue.

5. Climate Clash

When people ask Nury Turkel what the biggest obstacle in Washington, D.C., to his human rights efforts is today, he has a simple answer: environmental activists.

“They try to save the planet and care less about the real human being,” Turkel says. “We can fight genocide and ecocide at the same time.”

The Biden administration has struggled to strike that balance with China. Instead, officials have slowed down substantive responses to the genocide in Xinjiang as they weighed climate priorities. The debate gets to the heart of the future of U.S.-China relations: It’s no longer a question of whether China is an adversary or if America can change China’s behavior with economic investment. Instead, it’s a matter of whether the United States should compartmentalize issues and cooperate with a country actively committing genocide. And is cooperation even possible, when the country engaged in genocide often takes an all-or-nothing approach?

China’s uncompromising stance with climate talks cemented that dynamic, and it made human rights actions in the United States even more of a political minefield.

The Biden team’s internal argument over how to balance climate goals and human rights played out in the summer of 2021. In June, Customs and Border Protection banned imports from Hoshine Silicon, a Chinese solar manufacturer tied to forced labor. Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin reported shortly after the ban was announced that there had been a “fierce debate” inside the administration over the Hoshine sanctions, with some worrying it would disrupt the solar industry too much.

That debate only intensified in the following months as lawmakers sought a broader Xinjiang import ban. The timing was particularly sensitive with the November Glasgow climate summit approaching: Officials didn’t want to undercut the United States’ negotiating position or reduce the odds of new climate commitments from China.

Sen. Jeff Merkley, the Oregon Democrat who cosponsored the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, played a leading role in making the case for a strong response to the genocide but faced resistance from senior Biden officials about the legislation.

As the possibility of the forced labor bill passing became more real, he remembers, “I heard more concerns from the administration.”

When asked if he ever spoke directly to Biden or Kerry about the legislation, Merkley declines to answer. He says he actively petitioned high-ranking officials in favor of the bill in the summer and fall of 2021, rejecting the idea that climate priorities and human rights concerns should be in conflict. With a long track record on both human rights and climate policy, he was seen as one of the few lawmakers with the credibility to make that case.

He urged the White House to help businesses diversify climate supply chains and boost American production of solar panels, so the industry would not be complicit in slave labor.

“I did not see this as an irresolvable conflict,” he says. “It’s fair to say any administration has people who have a range of ideas and thoughts, and some folks within the administration really felt like this bill would be damaging for our efforts on climate. So I was trying to push back and say, ‘No, no. You all can address this successfully, and it’s essential for American leadership in the world, for who we are and our values, that we not import products tainted by slave labor.’”

Merkley summarizes his argument: “You can’t say it’s wrong to source cotton from Xinjiang and then turn around and say it’s okay to source solar panels.”

“The administration, again, has diverse voices that were wrestling with this dynamic, but I saw my role as to say, ‘If one has to come before the other, it’s human rights.’ And second of all, you can take proactive action to develop solar panels from elsewhere.”

China makes up nearly a third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. That, paired with its role in producing critical components for solar panels, underpins American officials’ hopes to get China on board with more ambitious climate commitments.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in his speech outlining the administration’s China policy last month that there is “simply no way to solve climate change without China’s leadership.”

Even with that reasoning—and setting aside the fact that Chinese solar panel materials are largely produced using dirty coal—Blinken’s language about working with China was at times bizarre to hear in a speech where he also noted the Chinese government is actively engaged in genocide. It frustrated human rights advocates, especially after they were pitted against climate priorities in getting the forced labor bill passed.

Merkley points to proposals to fund American solar manufacturing as an important way to disentangle the issues.

“One has to recognize that the fossil fuel side of the world also saw this as an opportunity to try to slow down the transition to renewables,” Merkley says of the forced labor bill.

Still, he wishes it had passed sooner.

“It wasn’t as if we suddenly realized near the end of last year that China was engaged in genocide,” he says.

When he gets the chance in meetings with foreign officials, Merkley brings up the problem of forced labor and market demand for solar components. During a conversation with Taiwanese diplomat Bi-khim Hsiao last November, Merkely says he pointed out an “opportunity for Taiwan to meet a big need in America, which is slave labor-free, inexpensive solar panels.”

John Smirnow, general counsel at the Solar Energy Industries Association, says some major solar brands have taken steps to trace their supply chains and move out of Xinjiang.

“We’re starting to see now the manufacturers develop new supply agreements, polysilicon, with German polysilicon manufacturers,” Smirnow says.

Some foreign companies are also ramping up operations in the United States. South Korean firm Hanwha Qcells announced in May it will spend $320 million to boost production at its Dalton, Georgia, factory beginning in 2023.

Moving supply chains can be complicated, though.

That’s why the Biden team fiercely debated sanctions in Xinjiang, and it’s why Kerry’s deputy at the time, Jonathan Pershing, reportedly told lawmakers the American government would need more time, something like five to 10 years, to move solar supply chains away from Xinjiang.

According to the Washington Post, Pershing said in meetings with members of Congress in 2021 that the administration wanted flexibility in the forced labor legislation for that transition. A State Department official speaking on the condition of anonymity claims Pershing wasn’t actively lobbying against the bill and the discussions reported by the Post came as part of broader briefings.

Similar arguments—that officials were not actively lobbying on the forced labor bill but were only answering questions about it from lawmakers, or that they were providing technical assistance on the details—were prominent from the White House in the latter half of 2021. Overt and sustained opposition from an administration isn’t always necessary to kill a bill, though. It can be difficult to gain traction on controversial measures if an administration isn’t actively supporting it. And members of the Biden team were privately pushing against the measure in conversations with lawmakers, mainly Merkley, during this time.

The State Department declined to provide more details about whom Pershing met with in Congress. Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office says he did not meet with her or her staff on the matter, although he may have participated in climate calls between Pelosi and Kerry during that time. McGovern’s office says the congressman did not meet with Pershing. Merkley’s office says they had meetings with Pershing on climate, but not on the forced labor bill.

Reluctance among some Biden administration officials didn’t stop the bill from winning resounding support in the Senate.

In July 2021, it passed that chamber for the first time without any opposition. Because it was different from the version House members passed the year before, and because it was a new Congress, members in that chamber would have to vote again on the matter to send it to the president’s desk.

After Senate passage, the senators who sponsored it hoped action would follow quickly in the House. It didn’t.

Congressional aides from both parties point to the Biden administration’s hesitancy and the timing of the climate summit as primary reasons the bill didn’t move any further for months after the Senate passed its version. Pelosi denies having been urged by the administration to delay the bill. When asked last year if Kerry had lobbied her to slow-walk the measure, she told reporters that was “completely not true.”

Pelosi’s office declined requests to interview her for this story.

House Democrats say there were other issues at play, including policy disagreements and a busy legislative calendar. Corporate resistance hadn’t subsided, either.

Rep. Jim McGovern, the Democrat who introduced the bill in the House, maintains the timing was not influenced by the White House, and in the later months of 2021 he felt sure it would ultimately pass.

House lawmakers weren’t going to simply take up the Senate-passed version, he says; they wanted to approve their own bill again with overwhelming margins to have a stronger negotiating hand on items like the SEC disclosures, which had been stripped from the Senate version. House Democratic leaders were also considering the bill as part of a larger China competition package, which was slowly working its way through Congress. McGovern says he was never told to hold up the legislation and that he never spoke to Kerry about it.

“If John Kerry was unnerved by this, I’ve known him for a hundred years,” McGovern says. They are both from Massachusetts.

“He’s my friend. I worked my ass off for president, for his Senate campaigns. We have a good, productive relationship. I would’ve thought that he would’ve called and said, ‘Hey, you know, slow down or do this.’ He didn’t.”

Kerry’s public comments about his trip to China in September 2021 sparked concern among advocates and the bill’s supporters, though, and there were no signs the House would be taking it up any time soon.

At first, the House’s delay after the Senate approved its version was explainable: The two versions of the bill still contained differences. Democrats were also making a push on President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda at the time, and the disastrous military withdrawal from Afghanistan was soon weighing heavily on members’ minds. But the weeks stretched into months with no movement on the legislation. Sponsors from the two chambers had no serious conversations at this point on how to rectify the bills’ discrepancies.

“We were optimistic, I guess, in July and August,” a Republican Senate aide involved in the effort says. “By late September, when we still really weren’t getting any real substantive responses, is when we started to think, okay, something here is wrong.”

Aggravation wasn’t limited to Republicans—Democrats who worked on the Senate version were also itching for progress.

“Frustration built over time,” one senior Democratic Senate aide says. “The point when it got really, really frustrating was when a version of this bill had passed both chambers in consecutive Congresses. It was like, alright. We know that this is something that has almost unanimous support. Let’s get it done.”

In November, more Republican lawmakers went public with their fears about the bill being stalled. A letter from GOP lawmakers on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, led by ranking member Rep. Mike McCaul, urged Pelosi to “stop delaying floor consideration” of the forced labor bill.

“It is extremely concerning that no legislation imposing real world consequences in response to this genocide has received floor consideration this Congress,” they wrote.

“This lengthy delay stands in contrast with the Democratic majority’s record on Uyghur issues under the prior administration.”

The members pointed out that the year before, House Democratic leaders brought the forced labor bill forward for a vote without waiting for it to go through committees.

“Both the House and Senate measures would pass the House resoundingly, if put up for a vote,” the GOP members said.

Each day the forced labor bill remained on ice in Congress was another day products made with forced labor were flowing into the United States. Members of Congress felt a sense of urgency.

The ongoing genocide, the Foreign Affairs Committee Republicans wrote in their letter to Pelosi, is “nothing less than the moral test of our time.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.