Debates about schooling are currently consumed by what appear to be twin puzzles.

Even as angst about critical race theory (CRT) and school masking mandates run rampant, parents tell pollsters that they continue to love their kids’ schools and teachers. Meanwhile, Americans report exhaustion with school reform of pretty much every stripe, even as parents say they’re hungry for novel options (including private school choice, homeschooling, and “learning pods”).

What’s going on? How can parents be simultaneously angst-ridden and satisfied? Exhausted by reform and hungry for options?

For starters, we need to appreciate that schools serve at least three key functions for students and families: the custodial, the social, and the academic.

In normal times, the custodial and social roles are the primary drivers of how parents think about schools. If the bus shows up on time each morning; there aren’t too many snow days or early dismissals; the school feels safe; and kids make friends, join some activity or other, and seem to like their teachers, most parents will defer to the experts on curriculum and instruction. This attachment to the custodial and social, along with a lack of visibility into classrooms, means that—absent clear evidence to the contrary—parents tend to trust that the educators have got the academic piece under control.

Last year upended all of those factors. When parents could no longer count on schools to pick up kids every morning, the rug was pulled out from under the custodial piece. When sports, clubs, cafeterias, and social interactions were shut down or wildly distorted, the same happened with the social dimension—leaving lots of parents worried about their kids’ mental and physical well-being.

Meanwhile, parents were suddenly offered an unprecedented window into what actually happens at school. Remote learning let parents see what kids were (or weren’t) learning. Parents suddenly had access to every assignment and reading, including those that seemed idiotic, ideological, or otherwise problematic. Asynchronous learning days, when students watched videos or did online assignments on their own, showed that a “full day” in many schools seemed to require less than an hour of learning—raising questions about just what students normally do all day.

Shorn of the custodial-social boost, schools faced unfamiliar scrutiny on the academic front. This helps make sense of the timing of the CRT backlash. After all, while the killing of George Floyd and the ensuing summer of “racial reckoning” served as an accelerant, the troubling materials and practices in question have been quietly wending their way into schools for several years. Given that, it’s pretty striking that things blew up at a time when huge numbers of schools were partially or wholly closed.

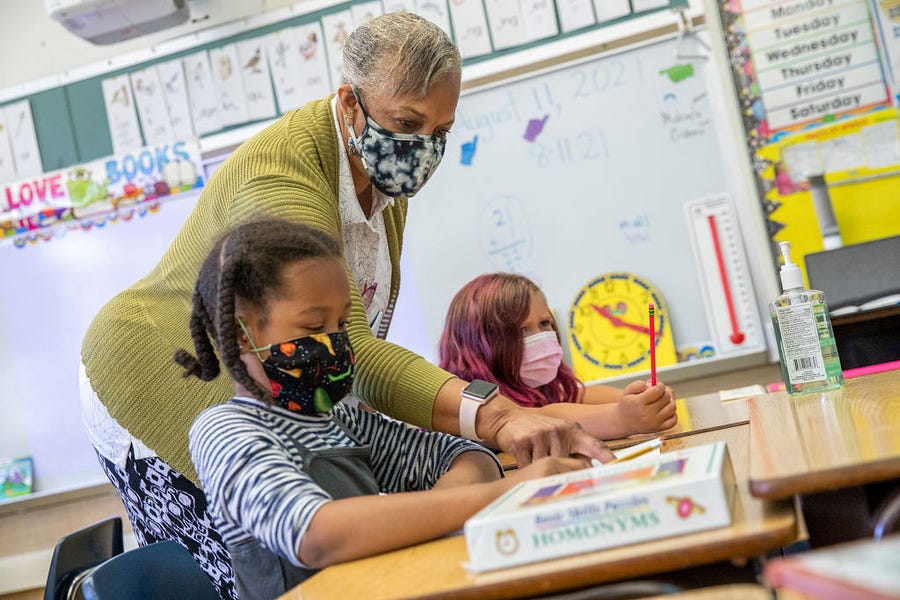

This year, of course, schools are open again. And, even as parents clash over CRT, masking, and vaccine mandates for kids, it’s playing out against a backdrop of growing normalcy. Parents see their kids going to school each day, interacting with friends, engaging with teachers, and participating in clubs. This doesn’t alleviate the angst, especially when it’s reinforced by yawning cultural polarization, but there are lots of preoccupied, non-activist parents looking for an excuse to turn back to other matters. But don’t mistake their quietude and relief for satisfaction.

That brings us to the second, more intriguing paradox—how parents can be both exhausted by school reform and hungry for options. For starters, recognize that, from a parental perspective, school reform has frequently had things backward. Reformers focus on how to change big systems in pursuit of sweeping slogans (“closing achievement gaps” or “college for all” or, today, “ending white supremacy”). For parents, this means they get a lot of encouragement to send an email, wear a T-shirt to the state capitol, or attend a school board meeting—in other words, actions that take time and energy, but which are unlikely to make an obvious difference for their kid.

Meanwhile, although efforts to change school or district policies can have a more immediate impact on students, they’re always a hard slog. That’s why savvy parents focus on dealing with specific hassles rather than system change: They call the principal to get their child reassigned from teacher A to teacher B, opt their kid out of an assignment, or ask a school board member to help get their kid into a program. In other words, they try to solve individual problems. They don’t get caught up in the slog of bureaucratic change.

Frustration boils over when schools make it hard for parents to solve these practical problems, leaving parents inclined to seek a viable alternative. Of course, low-income families (who can’t afford to move) and who may live in systems filled with struggling schools, can wind up feeling trapped and frustrated. What gets lost is that huge swaths of middle-class and suburban families can feel similarly stuck, especially if they bought their house because of the local schools and have made a life there. While suburban families may have resources, they frequently lack good alternatives: After all, elite private schools are largely an urban phenomenon, tony suburban private schools (even where they exist) can be too expensive for middle-class families, and (outside of Arizona) “good” charter schools tend to be urban phenomena focused intensely on serving low-income students.

In fact, as a general matter, school choice has not been concerned with empowering suburban parents. For three decades, school choice programs have been designed and marketed as a tool for serving low-income children in the urban core, while most of middle America has been told that school reform wasn’t about their kids. We saw that last year, when millions of families scrambling to assemble learning pods for kids locked out of school were informed by elite news outlets that they were trading in “white supremacy” by scrambling to provide their children with learning that wasn’t provided to every child. It was all more than a little reminiscent of the fights over No Child Left Behind, when suburban parents worried about cutbacks in arts, world languages, or gifted classes were told that they needed to worry less about what their kids needed and more on what the activists insisted would be good for all those other kids.

Well, all those middle-class and suburban parents have gotten the message: school reform is not about helping their kids; indeed, they’re part of the problem. Meanwhile, in a scenario that’s played out in communities from Newark to New Orleans, low-income families have felt ignored and ill-used by out-of-towners who show up with philanthropic dollars and their own reform agendas. It’s hard to blame anyone, especially after the past year and a half, for not wanting more “reform-minded” disruption.

So there’s not much appetite for “reform,” but there is for more and better options. Parents don’t want to sign up for some bit part in a Sisyphean effort to “reform” schools. But fully one-third report that they’re in a learning pod or are interested in joining one—including more than half of black parents and 45 percent of Latino parents. Heck, after a year in which the homeschooling population doubled to more than 10 percent of all students, it’s no great surprise most parents now say they’d like the option to retain some element of homeschooling going forward, even if that’s just one day a week.

Families also want the option of sending their kids to schools that reflect their own preferences. For now that might mean mask mandates or social distancing. But in the longer term, they want schools that respect their values and their faith, particularly on sensitive issues relating to gender and sexuality. They want schools that will make their children feel safe, welcome, and valued—and many parents understandably believe that voguish efforts to direct students to undertake “privilege walks” or engage in race-based “affinity groups” don’t do that.

The explanation of the seemingly paradoxical twin puzzles of parent opinion on schools turns out to be surprisingly straightforward. Parents don’t want reform. Especially if the buses are running, kids are making friends, and school feels safe, they don’t want policymakers denouncing their teachers or insisting that their school is “failing.” What they do want are good options, and plenty of them.

It’s hard for Democrats today to articulate this, much less act on it. (See, for example, Terry McAullffe’s comment during the Virginia gubernatorial debate this week that “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach.”) After all, their party is a constellation of the diversity consultants, progressive activists, education bureaucrats, and teachers unions that staff the schools, fought for school closures, champion CRT, embrace mask mandates, and are dead-set on defending the public school establishment. Thus, they’ve largely been reduced to promising vast new sums to subsidize and supersize the status quo in the vague hope that things will work out.

This creates an extraordinary opportunity for conservative policymakers who can get the principles and the politics right. It’s been said that 2021 was the “Year of School Choice.” Well, if conservative lawmakers can avoid the distractions and just meet parents where they are, we ain’t seen nothing yet.

Frederick M. Hess is the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.