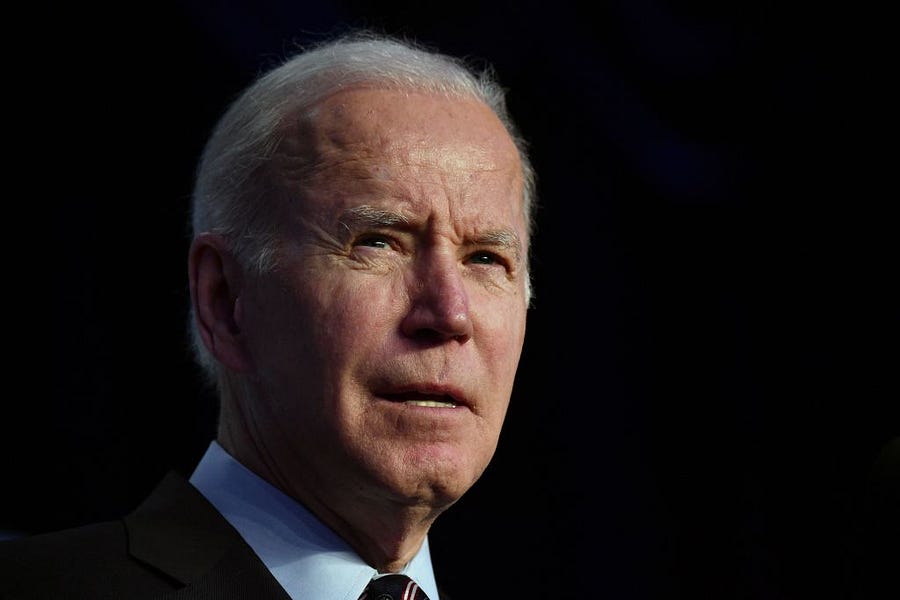

More than a year after his inauguration, it has become clear that President Biden’s foreign policy is not working. The horrific images in Ukraine and the chaos in global food and energy markets are the most dramatic signs that the American-led global order is under severe strain, but they are by no means the only ones. Having alienated traditional partners in the Persian Gulf, the administration is desperately searching for extra oil, even in Iran and Venezuela. However, Biden and his team are not the only people responsible for the decades of misjudgments and failures that squandered the commanding position the United States held at the end of the Cold War.

On one point, there is widespread, bipartisan consensus: U.S. foreign policy is adrift and needs to set a new course. Beyond that, there is still much under discussion. Although most Americans believe that China is a rival for global leadership, that Russia is a rapacious and aggressive power, and that something must be done it, Washington is abuzz with wildly varying plans and proposals about how to handle these revisionist adversaries. Looking back at two earlier shifts in U.S. foreign policy can bring some clarity to today’s questions.

Seventy-five years ago, on March 12, 1947, President Harry Truman told Congress that global events required the United States to dramatically increase its presence on the world stage. The British government had recently informed him that it could no longer support the Greek and Turkish governments against Communist pressure, and Truman asked Congress to foot the bill. However, the confrontation with the Soviet Union would extend well beyond this emergency measure: He announced the Truman Doctrine: “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” The Cold War was on.

Over the next several years, American commitments expanded rapidly. To help Western European countries fend off their internal Communist parties and recover economically from the war, the United States encouraged its European allies to coordinate in order to receive Marshall Plan aid. However, it quickly became apparent that political and economic measures would not suffice, and one year after the Truman Doctrine speech he asked Congress to reinstate the draft to rebuild the military that had shrunk rapidly after World War II. By the end of Truman’s presidency, the United States and its European allies had formed NATO and were fighting the Communist powers on the Korean Peninsula.

By the time that Richard Nixon moved into the White House, the Truman version of containment had proved unsustainable. The Soviet nuclear arsenal threatened to equal or outnumber American nuclear forces soon, and the balance of military power was growing unstable. After the fall of China in 1949, communism’s spread across the developing world proved to be too strong for the United States and its allies to halt at an acceptable cost. Attempting to stop the global spread of communism was challenging enough when the United States was by far the predominant economic power, but part of the U.S. strategy was to reduce the American share of the global economy. The Bretton Woods financial system gave American allies favorable exchange rates so they could rebuild after the World War II, and it succeeded so thoroughly that U.S. economic institutions were struggling to sustain the global financial system.

The alliance network was also under strain. As American allies grew stronger and thus more independent, they took steps that deeply concerned American policymakers: France pulled out of NATO’s command structure and pursued détente with the Soviet Union, and West Germany followed suit with an even more ambitious Ostpolitik peace program. The United States faced immense economic difficulties, was bogged down in Vietnam, and its key allies were flirting with the Communists. Something had to change.

The second major shift, which culminated in Nixon’s February 1972 visit to China, was to reduce American overseas commitments and pursue détente with the Soviets. In July 1969, Nixon told reporters in Guam “that as far as the problems of military defense, except for the threat of a major power involving nuclear weapons,” the United States expected its Asian partners to address their own security concerns. Pulling out of Vietnam was just one example of this Nixon Doctrine in action: As the military fell from 3.4 million to 2.3 million people in four years, garrisons in Japan, the Philippines and South Korea were slashed accordingly. Nixon also undid the exchange rate system that underpinned Bretton Woods and took the dollar off the gold standard. At the same time, the administration pursued a range of diplomatic initiatives with the Soviets, such as arms control talks, to limit the scope and scale of the Cold War.

As they did so, Nixon and his top foreign policy adviser, Henry Kissinger, endeavored to flip Soviet allies and other Communist countries. In the Middle East, they worked with Israel to neutralize Soviet initiatives and eventually made Egypt’s Anwar Sadat realize that a partnership with the United States was a precondition for settling territorial disputes with Israel, and they relentlessly diminished Soviet power and authority in the Middle East. They collaborated with dictators in Latin America and Africa to suppress Communist supporters. And the major prize was the 1972 trip to Beijing, during which Nixon established a relationship that forced the Soviets to deploy significant military forces along the Sino-Russian border and created other strategic opportunities. These diplomatic successes made up for other reverses and gave the United States a more durable foundation to prosecute and eventually win the Cold War.

Although Nixon’s strategy aimed for calmer competition with the Soviets and a more durable American position, it generated immense risks and ultimately was too unpopular to sustain. Getting out of Vietnam proved to be harder than anticipated, and Nixon invaded Cambodia and Laos before he could withdraw American troops entirely. More dangerously, U.S. nuclear forces went on heightened alert in 1969 and 1973: Détente was less successful at curbing nuclear brinkmanship than many hoped. Moreover, the détente strategy’s reduced emphasis on ideological competition was intolerable for many Americans: Disgusted by Nixon’s and Kissinger’s realpolitik, voters elected Jimmy Carter, whose emphasis on human rights and distaste for hard power was the polar opposite of Richard Nixon and led to catastrophic failures.

The Truman and Nixon doctrines offer different templates for policy today. A Trumanesque strategy would entail a more unilateralist, forward-leaning foreign policy that placed ideology at the heart of the confrontation with the revisionist powers. It would require major increases in defense spending and a series of major addresses from President Biden and his top advisers explaining the stakes of the confrontation and the urgent need for American action. Military officers and diplomats would devise plans to disrupt Chinese and Russian overseas operations; economic planners would build up partners and allies.

There are some significant dangers in the Truman 2.0 approach. Ramping up the competition so quickly would engender a backlash by U.S. adversaries that could lead to a conflict with catastrophic results. It could also exhaust the United States early in a competition that is likely to last for many decades to come. The Truman strategy started to falter against a weak Soviet Union and a semi-industrialized China: China and Russia each have major economic challenges today, but their relative strength is much greater than it was in 1947.

A neo-Nixon doctrine would look very different from the Truman one. The American military would cut capabilities in secondary theaters and hope that allies would pick up the slack. Diplomats would attempt to force a split between China and Russia, perhaps even by giving Russia concessions that many find distasteful. The U.S.-Taiwan relationship was a casualty of the opening to China; perhaps Ukraine and some NATO allies would assuage Vladimir Putin. It would also aggressively rebalance the American trade portfolio away from our allies and toward domestic production. Nixon attempted to address trade imbalances by moving toward a floating exchange rate in which markets set the value of the dollar. Today, this would require tariff hikes significantly above anything the Trump administration countenanced. Human rights diplomacy, of course, would virtually disappear.

This strategy also has other major downsides. The opening to China was a major component of this strategy, but it was possible because of a Sino-Soviet split that had driven the rival Communist powers into a quasi-war in 1969. There is no sign that such a major break is occurring, or close to occurring, today. Another danger with scaling back commitments is that as you withdraw, your opponent will advance to find the new boundaries of the confrontation. This dynamic necessarily leads to collisions that can become very dangerous, as the 1969 and 1973 nuclear alerts show. Moreover, U.S. allies and partners are more capable than they were in Truman’s time, but most of their security concerns come from major powers like China and Russia, not insurgents or local proxies, so a carbon copy of the Nixon Doctrine would not necessarily reduce that many American commitments. Cold-eyed foreign policy also rarely satisfies the American public for long, and visible signs of collapse, such as the fall of Saigon or the Afghanistan fiasco, alienate public opinion.

However, there are elements from both strategies that the Biden administration could fruitfully employ today. Ramping up the defense budget to 4 percent of GDP, which is well below the Cold War average, would give policymakers significant additional capabilities and warn adversaries of the perils of crossing Uncle Sam. In Truman’s time, the defense buildup was necessary because relatively few allies and partners could defend themselves; today, major partners like Germany and Japan have underfunded their defense for too long, but they are moving in the right direction, and the United States can maintain order in strategic regions at less cost than before.

For this strategy to work, the U.S. will have to be more responsive to the concerns of allies and partners—even the unsavory ones. Americans are seeing the costs of alienating important partners like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates every time they fill up their cars, and there are other regimes—particularly in Asia—that can contribute to regional order and American interests if they have incentives to do so. Nixon and Kissinger were able to leverage their own allies to flip Soviet ones in part because everyone knew that America had its allies’ backs in a crisis. Today, many countries have reasonable grounds for questioning whether the Americans will help them in a pinch. One way to strengthen these ties is to stop importing goods with strategic implications from U.S. adversaries and shift production to allied and partner nations. Another is to realize, just as Truman and Nixon did, that as the international environment becomes more threatening, some human rights concerns will have to be left unaddressed.

The ideological dimension, if not handled correctly, can easily derail a strategy and lead to significant gains for adversaries. As both China and Russia have made clear, they see some aspects of American ideology, such as free speech, as fundamental threats to the regime. Beijing and Moscow do not have a formal set of doctrines they wish to spread, but they perceive the current confrontation as an ideological one. However, many important American allies and partners, such as India, are not interested in joining a crusade for Western values. American leaders must identify and articulate a set of principles, such as defending a world order where Americans are free to live as they choose, that Americans can rally behind and that the U.S. government can plausibly claim it is defending abroad without alienating key partners.

The shocking scenes coming out of Ukraine remind us that the costs of American failure are real and very high. The United States and its allies cannot prevent every needless death and forestall every tragedy, but with resolution, prudence, and the blessings of providence we can defend our ways of life. We have the tools we need to do so. The question is if we will use those means effectively.

Mike Watson is the associate director of Hudson Institute’s Center for the Future of Liberal Society.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.