Moby Dick is hardly a topic guaranteed to provoke belly laughs. Unless, that is, you’re talking to the acclaimed novelist Christopher Buckley and he’s showcasing his impression of a certain ex-president: “We’re gonna kill this whale, folks! And it’s gonna be beautiful, so beautiful when I stick that harpoon in. And I’m the greatest of all harpooners, you know I am.”

And it isn’t just 19th century tales of whale hunting; Buckley can make anything funny, and recently did exactly that when he indulged me with a lengthy Zoom call on an otherwise gloomy COVID afternoon. Together, we explored subjects ranging from the struggles and satisfactions of writing to the impertinence of Balty, his Bernese Mountain Dog, who repeatedly injected his snout into the proceedings. Unsurprisingly, we spent almost every second of our conversation giggling heartily.

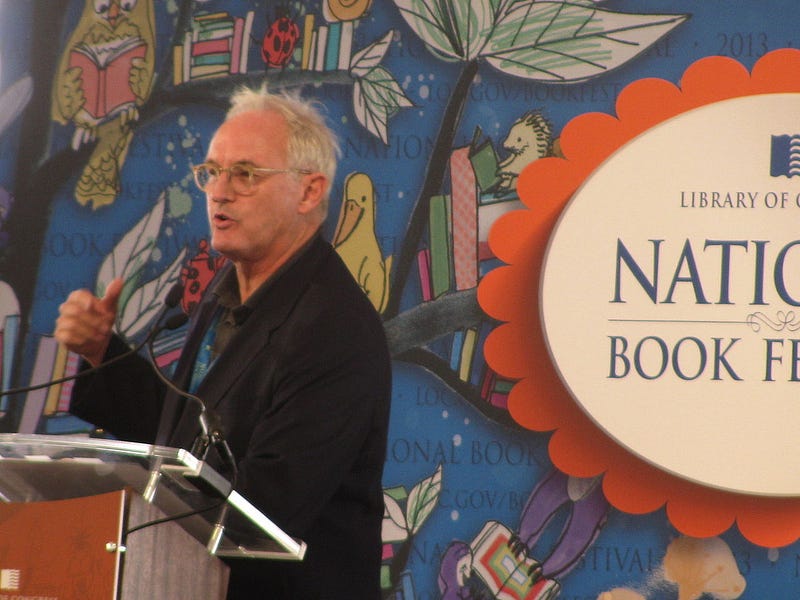

Since the publication of his first novel, The White House Mess, in 1986, Buckley has risen to become America’s foremost literary satirist by lampooning cultural and political institutions in a manner that is always sharp but never callous. America, Buckley wrote in Boomsday (2007), is a “lunatic asylum, without enough attendants or tranquilizers.”

Droll portrayals of Washington life are Buckley’s forte. In his fiction, D.C. is defined by overlapping conspiracy theories, feckless House politicians, and presidencies that would seem impossibly chaotic if not for the last five years. And yet it was Donald Trump, who convinced him to return to political satire in 2020 after an extended hiatus that began in 2012. “I’d reached the conclusion that American politics were sufficiently self-satirizing,” Buckley told me, reflecting on the rise of Sarah Palin and the broader strangeness of the Obama era. “And so I wrote two historical novels. The books did okay, but it was pretty clear that wasn’t what people wanted from me.”

While Buckley was finishing up and publishing the latter of those novels, The Relic Master (2018), a former reality TV host with an irrational fear of wind power had moved into the Oval Office. “You had this freak show going on, this carnival of sadness,” Buckley recalled. “People kept saying to me, ‘Why aren’t you writing about this?’”

Viewing Trump as his own best parody, Buckley was reluctant to make him the subject of a book, but eventually submitted. The resulting novel, Make Russia Great Again, was published last year. It primarily concerns Trump’s bromance with Vladimir Putin, which Buckley found so unusual that it would be wasteful not to mock. “As Juvenal said, ‘Who can not engage in satire?’” Buckley remarked. “Especially in such times.”

During our meeting, Buckley discussed his oeuvre with glee, but also a tinge of displeasure at how the literary establishment regards comic works. “P.J. O’Rourke once said that ‘humor sits at the children’s table of literature,’” he told me. “There’s a general sense among the cognoscenti that it’s a second-tier genre; it’s not really considered sérieux. How many Pulitzer Prizes go to humorists?”

Tom Wolfe, perhaps modern American literature’s funniest social observer and a tremendous influence on Buckley, faced this reality firsthand in 1998 with the release of his second novel, A Man in Full. The book saw Wolfe aim his cane at racial politics in the South and the excesses of Atlanta’s elite. Despite high sales, it incurred the wrath of three giants of American prose: John Updike, Norman Mailer, and John Irving. Wolfe labeled the trio his “three stooges” in the war of words that ensued.

Updike’s review of the novel in The New Yorker was particularly telling. He declared that it merely “amounts to entertainment, not literature, even literature in a modest aspirant form.” After dedicating years of research and delicate rewriting to A Man in Full, Wolfe was condemned to the literary kindergarten for the crime of wanting his readers to enjoy themselves.. How fitting it is that Updike won two Pulitzer Prizes for Fiction to Wolfe’s zero.

But humorous is not synonymous with unserious. BuckleRejecting the idea that satire is an inferior genre, Buckley provided several examples to the contrary. “I would cite Dean Swift: Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal. Catch-22 was a hugely influential book; a satire set in World War II that was really about Vietnam.”

Before A Man in Full came The Bonfire of the Vanities, Tom Wolfe’s epic sendup of Reagan-era New York. Through fiction, Wolfe sought to produce grand works of social realism that would authentically capture life in a vast nation, as a tip of the white fedora to Dickens, Balzac, and Zola. He penned all of his novels by engaging with the country around him, and crafted in Bonfire an irresistibly funny portrait of the typical American city. Ethnic tensions, ubiquitous greed, and the image of an opulent financial center surrounded by almost dystopian inner-city neighborhoods afforded him ideally ludicrous material. Wolfe’s work forced Americans to confront disagreeable social realities while revealing those realities to the wider world.

Buckley recognizes today what Wolfe and Heller understood before him: that there is no richer source of literary material than real life, and that real life is a comedy. Readers crave stories of equal scale and strangeness to their everyday experiences in what Wolfe described as this “wild, bizarre, unpredictable, Hog-stomping Baroque country of ours.” The quotidian in America is often ridiculous, and the ridiculous demands to be parodied.

Great satire, then, serves a higher purpose. “I write funny books,” Buckley told me, “but I like to think they’re actually about something.” In Thank You for Smoking (1994), for instance, he explored through the prism of big tobacco the notion that lobbyists should, in a free society, be allowed to profit from death and disease inflicted by products they propagate. Make Russia Great Again, meanwhile, prods at media decay and political degradation. “Proud Boys,” Buckley scoffed when our conversation turned to such matters. “How proud are we as Americans?”

Indeed, the degradation we have witnessed in recent years is devastating. War, urban dysfunction, and the nefarious schemes of cigarette peddlers are similarly unpleasant. Yet they are also absurd, and can be put to productive use in a fictional context. As the novels referenced above illustrate, satire is a vital artistic tool. It allows writers to convert the tragic into the enjoyable, so that we can confront and withstand it. A satirist, Buckley wrote in Losing Mum and Pup (2009), is somebody who “blows raspberries at the cosmos.” Raspberries, it turns out, can be truly profound.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.