In ordinary times, secretary of state tends to be a low-profile role at the state level. But a bevy of candidates loud and proud in their denials of the 2020 election results are running for the position in several states next month pledging to overhaul their state’s election systems.

Though the power of the position varies by state, the secretary of state doesn’t have absolute authority over elections. “It’s not as if this is an all-powerful person with no other actors, no other restraints and obstacles,” said John Fortier, a senior fellow on election administration at American Enterprise Institute. “They’re going to take the oath of office, they’re going to have to follow the law. They’re going to have to interact with both the executive branch, legislative, and local officials.”

But that hasn’t stopped some from campaigning on wholesale changes.

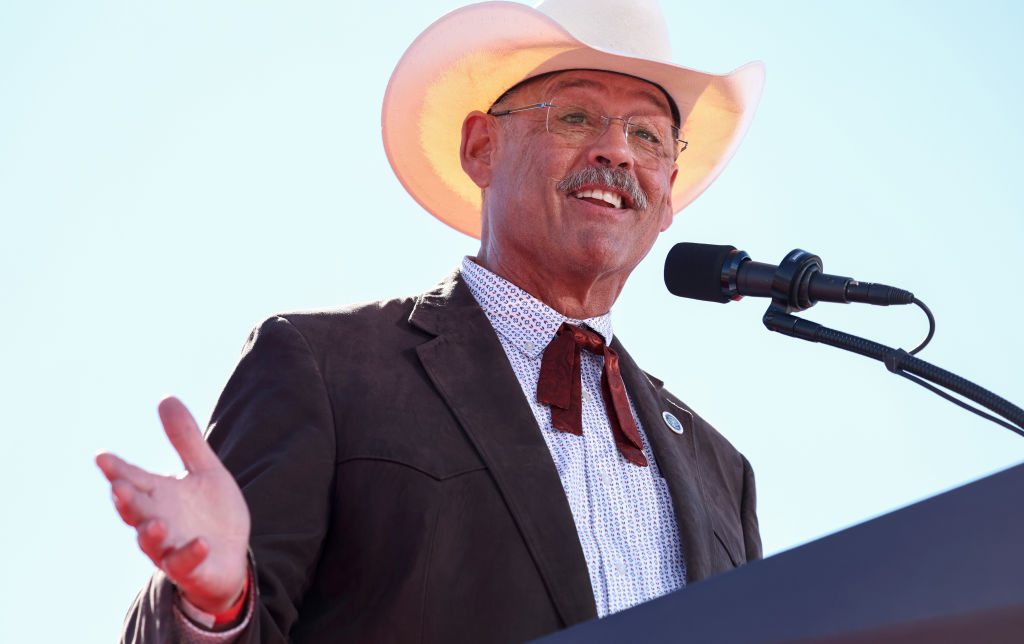

Arizona state Rep. Mark Finchem, the GOP nominee for secretary of state, told supporters in May that if he had been in office in 2020, “we would have won. Plain and simple.”

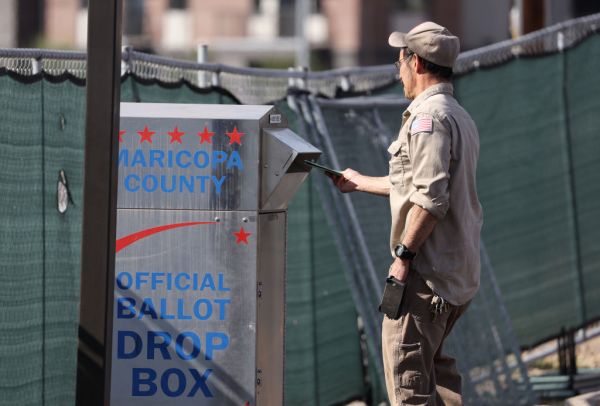

Finchem has touted conspiracy theories that Democrats stole the election from Donald Trump in key counties like Maricopa and Pima and has questioned the constitutionality of early voting. Earlier this year he introduced a bill to let the state assembly throw out the 2020 election results. The proposal would also have instituted universal voter ID, required nearly all voting to happen on Election Day, and, with a few exceptions, required votes to be cast in person and counted by hand.

After Finchem won the GOP primary, Barrett Marson, a GOP consultant in the state, decided to vote for his Democratic opponent, Adrian Fontes. “I do trust that he’ll follow the will of the voters,” Marson told The Dispatch. “And I don’t trust that Finchem would do the same.”

In Nevada, GOP secretary of state candidate Jim Marchant has claimed that he is a victim of election fraud. In 2020, Marchant refused to concede when Democratic Rep. Steven Horsford won Nevada’s 4th Congressional District by around 5 points. He unsuccessfully sued, then supported the group of Republicans who signed fake electoral certificates in Trump’s favor. As a candidate for secretary of state, Marchant said his “number one priority will be to overhaul the fraudulent election system.” He’s called for abolishing mail-in ballots and replacing them with electronic voting machines. (Nevada moved to a universal mail voting system in 2021.)

Voters don’t directly elect all secretaries of state: Pennsylvania’s, for instance, is appointed by the governor. GOP gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano, who as a state senator tried to block certification of the 2020 election, has said he wants to work with the legislature to overhaul election law. He’s proposed a constitutional amendment that would eliminate “no-excuse” mail in voting.

Over a dozen non-battleground states feature Trump-aligned secretary of state candidates as well, including New Mexico, Indiana, Alabama, and Ohio, according to the nonpartisan group States United Action. Election-denying candidates lost to more mainstream Republicans this cycle in primaries in Georgia, California, Colorado, Kansas, Idaho, South Carolina, and Nebraska.*

Many of these races may hinge on more notable top-of-ticket contests.

“We live in an era where you have the low information voter who just doesn’t see campaign ads, doesn’t do the research,” Marson said. “You get people who are upset about Joe Biden and the economy and inflation and they’re going to vote Republicans here, without ever really studying the candidates.”

A poll by OH Predictive Insights found last month that Finchem leads the race by 5 points, 40 percent to 35 percent, with 25 percent of likely voters unsure of their preference and 17 percent saying they had never heard of either candidate. A CNN poll this month found a 4-percent advantage for Finchem in Arizona.

In Nevada, Marchant has a slim advantage, the same CNN poll found, with 46 percent of voters supporting him and 43 percent of voters supporting Democrat Cisco Aguilar. In Pennsylvania, Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, leads Mastriano by over 6 percent, according to the RealClearPolitics average.

If elected, most would need the state legislature—and the governor’s signature—to make changes to state law. But David Becker, executive director of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research, thinks election-denying candidates who win could try to gum up processes on a bureaucratic level, “all toward the end of creating more uncertainty in the post-election period that could allow a losing candidate to claim that the election was stolen.”

Secretaries in some states (like Arizona) can rewrite directives to local election officials that outline processes like signature matching, vote-counting, and provisional ballots. If elected, a candidate like Finchem could rewrite regulations to make it harder for Americans to request absentee ballots or update voter information. Secretaries could also try to pressure election administrators to leave and fill those positions with allies instead.

Secretaries of state could also order superfluous post-election audits or refuse to certify results.

“The question is, how robust are our checks and balances that if someone like secretary of state decides to not do their job as written in the state constitution, will they be overruled?” said Ryan Burge, an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University.

Some states certify results through a bipartisan state board of elections or a combination of a board and the top election official.

If for some reason an official chooses not to follow election procedure and sign off on results, courts could have a role to play.

When the Otero County (New Mexico) Commission refused to certify the 2022 primary election results, the state government sued. The state supreme court eventually forced the commissioners to certify the results.

Burge thinks it unlikely that a recalcitrant official who chose not to sign off on an election would be successful: “I don’t see a scenario where a state supreme court would allow a secretary of state to decertify an election.”

But Becker worries about a state’s chief election official “increasing the uncertainty in a post-election period.” He added: “I expect we’re going to see more of that in the aftermath of the ’22 election.”

*Correction, October 27, 2022: The story has been corrected to note that mainstream Republicans won in secretary of state races in California, Colorado, South Carolina, and Kansas and to update the number of races featuring a Trump-aligned candidate.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.