Dear Reader (excluding any of you who contributed to Florida’s giant African land snail crisis),

Long ago, I gave up on the hope that I might remember the bulk of what I’ve read. I’ve now reached the point in my life where I struggle to remember a significant portion of what I’ve written. By my reckoning—not counting books, bathroom graffiti, or fake prescriptions—I’ve averaged between 5,000 and 10,000 words a week for two decades. One version of a famous literary anecdote has it that when Truman Capote was told that Jack Kerouac never revised his writing after the first draft, Capote responded, “That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

Well, going by that definition, this “news”letter has contained a lot of typing over the years.

Whatever you want to call it, one thing that emerges from so much … writing? typing? wordsmithery? composition? … are certain themes. I suspect this is inevitable for all writers because it is inherent to the craft.

For instance, one of my favorite web resources is TV Tropes, in part because it reminds us that there is a finite inventory of morals to relate through an infinite inventory of stories. Now, finite doesn’t mean small or scarce. There’s a finite number of stars in the galaxy (about 100 billion, give or take a few), but whatever the number is, that’s the number. And whatever that number is, it’s a tiny slice of the total number of stars in the universe. The Milky Way is just one of an estimated 100 billion galaxies. If you ask me, that’s way too many galaxies.

“Unrequited love,” “it’s the journey not the destination,” “power corrupts,” “the hero’s journey,” “the immortal who’s seen it all”—these tropes or ones like them appear again and again in stories from antiquity to the reboot of iCarly. Talk to a TV writer or novelist and they’ll likely compare themself to a chef who takes familiar ingredients and combines them in (hopefully) new ways.

This is one of the reasons I like science fiction and fantasy. There’s something inherently conservative about these genres, because while everything physical changes—Spaceships! Dragons! A Kryptonian bottle-city ruled by super-intelligent basset hounds!—the one constant is human nature. Even if the characters aren’t humans, the access point for the reader is their own humanity. Moreover, just because the characters aren’t humans doesn’t mean we don’t relate to them based on their internal humanity. The rabbits in Watership Down are only understandable because of they’re people underneath their leporine facades. Pixar or Disney would never make a cartoon about bears or lions that is truthful about the nature of bears and lions, because nobody wants to take their kids to see vicious animals tear apart terrified cute animals or people. Simba and Winnie are compelling because they’re humans underneath the fur.

But if we’re all drawing from the same warehouse, I think the eternal recurrence of themes is a much more prominent part of the job description for conservative writers. Take the above point about human nature being a constant. It’s a central tenet of conservatism and appears in the work of virtually every conservative writer I can think of. It is to conservative analysis what salt or heat is to cuisine—an essential part of the craft. Sure, there are recipes that don’t involve cooking or salt, and some are good. But they’re the exceptions.

One theme I’ve come back to time and time again is that rules—norms, laws, manners, morals, customs, ethics, best practices, etc.—exist as a way to outsource decision-making. When we see a red light, we hit the brakes. It may not be necessary in the moment—what if the roads are empty?—but we usually do it anyway. Rules liberate us from having to reinvent the wheel in every situation. Twenty-three years ago, I argued that A Simple Plan, a largely ignored movie, was one of the most profoundly conservative films in recent memory. Why? Because the whole movie rests on the premise that the basic rules of right and wrong protect us from the unpredictable chaos we invite when we invent morality on the fly. As I’ve written, that’s the moral of Breaking Bad, Sons of Anarchy, and countless other tales of “stay on the path” morality.

Of course, sometimes one set of rules conflicts with another. This often drives heroes to say, “Screw the rules, I’m doing what’s right!” and villains—or their henchmen—to say, “I was just following orders.”

The reason we heap scorn on the phrase “just following orders” is that it’s a euphemism for the “Nuremberg defense.”

But it’s worth thinking through why the Nuremberg defense is grotesque. We do not think that, say, Adolf Eichmann was a villain because he failed to independently think through whether it was good policy to send Jews by the trainload to their deaths. If he’d done all of his “due diligence” by reasoning his way through all of the competing arguments and concluded that, yes, he should help liquidate whole families and communities, we wouldn’t think he was any less evil. Indeed, we’d properly conclude he was even more evil. Just following orders is a defense, it’s just a very weak one in his case because by following the Nazi’s rules, he was violating even more important rules. You can express these rules in theological, moral, or secular-ethical terms, but nearly all of us recognize that at the testing point, those higher laws are more important and should be more binding.

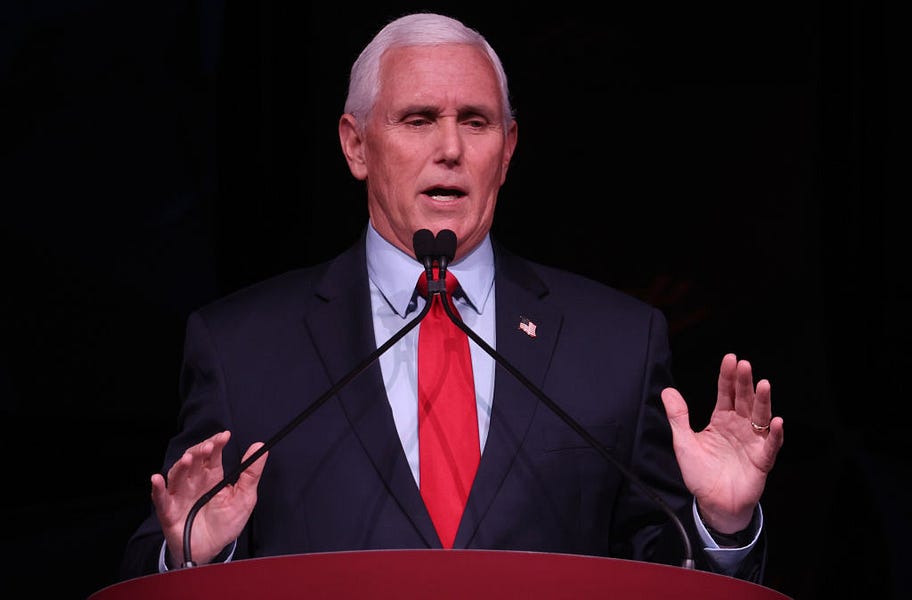

There are scores of familiar scenarios where moral law trumps conventional law. If I steal your car to get a gravely wounded child to the E.R., no jury is going to send me to jail. I’ll give you a more newsy example. Mike Pence unconstitutionally deployed the U.S. military to quell the riots on January 6. He had no authority to do it. But as Noah Rothman puts it, “Mike Pence Broke the Constitution on January 6—But Only to Save It.”

Gen. Mark Milley dismissed Mark Meadows’ B.S. as “politics, politics, politics.” But when Pence told him and the secretary of the army to deploy the National Guard, they followed his orders. If you reversed the situation and had a president making the right decisions and the vice president intervening to make self-serving political decisions, it would look a lot like a Latin American coup. But Pence broke the rules for the right reasons because there were more important rules at play. I never imagined I would ever compare Pence to Charles de Gaulle, but when de Gaulle declared himself the leader of the Free French and denounced Phillipe Pétain as a traitor, there weren’t many legal niceties to support his position. He just did the right thing.

Careful what you wish for.

A few days before Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, I wrote a column on how Putin should be careful what he wishes for. Sure, he can invade Ukraine, but that doesn’t mean he will succeed in his objectives or be able to control events once he ventures off the geopolitical equivalent of the right path. I was right. He has failed in all of his initial ambitions and he’s now trying to salvage his misbegotten crime. As Joe Biden said this week—in what was the first good, original line I’ve heard from him in years—Putin “wanted the Finland-ization of NATO. He got the NATO-ization of Finland.”

Perhaps second only to the permanence of human nature, one of the most fundamentally conservative insights—small-c and big-C—is that reality bites back. You can’t simply use reason or will to impose your vision on the world without inviting the world pushing back in unexpected ways. While the forms of unintended consequences are by nature unpredictable, that there will be unintended consequences to any major reform or policy initiative is one of the most enduring conservative cautions going back, at least, to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France.

Everywhere I look today, I see people on the left and right ignoring this basic principle. The bulk of Joe Biden’s problems stem from his victories, not his losses. His spending didn’t create inflation, but it did contribute to it and makes him seem politically responsible for it. He got his way in Afghanistan thinking he’d be a hero for it, but his reputation never recovered—and rightly so. Democrats considered it a massive triumph to win the Senate elections in Georgia, but Biden’s nominal control of the Senate has served only to make him look ineffectual. If there was ever an idea that provided a more obvious reason to shout, “Careful what you wish for!” than the left’s obsession with abolishing the filibuster, I don’t know what it is. More broadly, progressives have racked up all sorts of policy and cultural wins only to suffer from the inevitable blowback to them.

Nearly all of Donald Trump’s failures stem from his belief that he can will his narcissistic vision on the world. He thinks he can make the world believe he didn’t really lose. He thought he could simply reenact Mussolini’s march on Rome and stay president. His enablers got caught up in the same mind warp, believing they could just brazen their way through to victory. They took shortcuts, made decisions based on making up morality and—in the cases of Eastman and Clarke—the law on the fly. They wandered off the path and invited the chaos.

This week, I wrote that the overturning of Roe v. Wade was the biggest victory in the history of the conservative movement. It was, and I agree with the Supreme Court’s reasoning. I wouldn’t tell sincere pro-lifers “be careful what you wish for” because most of them—or at least most of the ones I know—would gladly trade short term political damage to the GOP for success in pursuit of the higher good as they see it. But Republicans generally are deluding themselves if they think there isn’t ample opportunity for the law of unintended consequences to bite back hard.

Woe, woe, woe, feelings.

The conservative argument for staying on the path and doing the right thing even when you think you can get away with reaping the rewards for doing the wrong thing is usually an argument against the seductive and corrupting power of excessive reason, rationalism, or “scientism.” The technocratic mindset tends to drive progressives and other lovers of planning to think that tradition, customs, norms, etc. are relics. What the Tom Friedmans of the world want are “optimal policies” and they look askance at fusty old rules that stand in their way. That’s why Friedman wanted us to be China for a day—so we could sweep aside the archaic guardrails that make imposing optimal policies so difficult. Friedrich Hayek and the Founders have all the best arguments against this sort of straying from the path.

But the conservative critique isn’t merely a jeremiad against excessive rationalism and technocracy. It’s just as easy—often easier—to venture off the path because you’re pissed off. Rage often comes first and we make reason a slave to that passion. Usually, if something isn’t a good idea, a person’s motivations for doing something stupid or evil don’t really matter. “Do not enter the bear pit” is good advice whether you want to jump in out of anger or because you think you’re smart enough to avoid the risks therein.

I don’t know whether John Eastman was fueled with anger at what he honestly believed to be a stolen election or motivated by the arrogance of intellect or an appetite for power. The point remains that he made the wrong decision to push for a lawless deviation from the rules for his team.

But whatever reasoning—or lack thereof—that went into the decision, the broader fact is that across the political spectrum, combatants are arguing as much from anger as from reason. The ubiquitous cultivation of rage in our politics is a siren song to venture off the path; to disregard the norms; to shout, “Screw the rules!” It’s a calling to take a shortcut on the mistaken belief that the rules are for suckers and that the enemies’ rule-breaking is a justification for your own.

If you’re turned off by the word conservative, fine. Wisdom, if it tells us anything, tells us that the rules matter more for the hard cases, when passions are high and the shortcut to victory seems obvious. Indeed, we have rules for the hard cases precisely because it takes no courage to follow the rules when it’s easy. “Courage is not simply one of the virtues,” C.S. Lewis observed, “but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality.”

There’s a reason we tell people to sleep on big decisions rather than making a choice when they’re overcome with emotion, because intense emotions can seduce us into making bad decisions. But everywhere you look, politicians, activists, and rabble-rousers tell us you’re not angry enough. These days, “mobilize” is just a political consultant’s term to get our voters as pissed off as possible. This is unsustainable. It is dangerous. And it will not lead to permanent victory, but permanent political warfare and the law of unintended consequences. Human nature—and conservatism itself—stands athwart all of this folly, shouting, “Stop!” Permanent political warfare need not stop at being merely political, and a people in a constant state of rage cannot be free. “It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things,” Edmund Burke writes, “that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.”

Canine update: After a welcome respite from fox shenanigans, the beast returned this week and Pippa was there for it. She woke us up the other night at 2:30 in the morning and spent a good 20 minutes shouting, “Get off my lawn!” at it. She was very proud of herself. Curiously, Zoë did not feel the threat warranted a similar effort from her. Indeed, Zoë is increasingly acting like an Israeli bodyguard. If you’ve been around them you know what I mean. They seem almost bored by minor potential threats but they’re always prepared to go full-tilt when it’s go-time. Meanwhile, Pippa has been behaving more like a spanielized Iron Dome system, constantly chasing away (at least in her mind) the crow menace or barking away the foxes. Pippa hasn’t lost her effulgent sweetness, nor has Zoë shed her stoic confidence, but they’re diverging in priorities. Pip is less interested in treats than Zoë and Zoë is much more concerned about containing Gracie and her will to power. And even when Pip takes things very seriously, she’s still silly.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.