Happy Friday! We hope you have a better day than whichever corporate comms official at McDonald’s let this description of the chain’s food slip into an article on a new menu revamp: “We can do it quick, fast and safe, but it doesn’t necessarily taste great,” said Chris Young, McDonald’s senior director of global menu strategy. “So we want to incorporate quality into where we’re at.”

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

- After a weeklong pause in fighting, a temporary ceasefire agreement between Hamas and Israel to allow for the release of hostages from Gaza expired early this morning, with fighting resuming within minutes of the deal officially ending. Israeli officials said Friday morning Hamas had “violated the framework” of the deal and failed to meet its obligation to release all women held captive, reiterating Israel’s goal of eliminating the terrorist group. The truce’s expiration followed the return of eight additional Israeli hostages, as well as two Russian-Israeli nationals, in exchange for Israel’s release of 23 Palestinian prisoners on Thursday. Also on Thursday, Hamas claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack on a bus stop in Jerusalem, in which two armed attackers—brothers identified by Hamas as members of its Al-Qassam Brigades—shot and killed three civilians and wounded five others before off-duty soldiers and a civilian intervened, killing both assailants. The soldiers mistook the armed civilian as another attacker and fatally wounded him.

- The House Judiciary Committee on Wednesday issued subpoenas for two former Biden administration officials in its investigation into the White House’s alleged attempts to censor content on social media platforms. Andy Slavitt, the former White House senior adviser for the COVID response, and Robert Flaherty, the former White House director of digital strategy, were both ordered by the committee to appear for testimony in January. The Supreme Court will also hear a case brought by the Republican attorneys general of Missouri and Louisiana over the same censorship allegations.

- In a party-line vote that some Republicans boycotted in protest, Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee authorized subpoenas for Harlan Crow, a Texas billionaire with ties to Justice Clarence Thomas, and Leonard Leo, a conservative legal activist. The authorization comes as the committee continues its investigation into the Supreme Court’s ethical guidelines and practices, and seeks information and documents from Crow and Leo on trips and gifts they provided to justices. Enforcing compliance with the subpoenas would require a full Senate vote and overcoming a Republican filibuster—to which Sen. Lindsey Graham said, “You know you’re not going to get 60 votes for these subpoenas.” (Disclosure: Harlan Crow is a minority investor in The Dispatch and a friend of the founders.)

- The personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, increased 3 percent year-over-year in October, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday—down from a 3.4 percent annual rate one month earlier. After stripping out more volatile food and energy prices, core PCE increased at a 3.5 percent annual rate in October, well above the Fed’s 2 percent target, but the smallest year-over-year gain since April 2021. Consumer spending, meanwhile, increased just 0.2 percent last month after increasing 0.7 percent in September.

- The House will vote today on a resolution to expel Republican Rep. George Santos of New York from Congress, potentially making him the sixth-ever lawmaker to be ejected from the lower chamber. The vote comes after a damning House Ethics Committee report found “substantial evidence” that Santos broke federal law—the congressman currently faces a 23-count federal indictment on fraud and money laundering charges, among others. After the ethics report was released, Santos announced that he wouldn’t seek reelection at the end of his term, but at a press conference Thursday morning, he suggested he might run for public office again. “I’m 35 years old,” he said. “It does not mean it’s goodbye forever.”

- A New York appeals court on Thursday reinstated the gag order in former President Donald Trump’s civil fraud case. The order—put in place by Justice Arthur Engoron to prevent Trump and his lawyers from publicly attacking his court staff—was briefly halted after an appeal from Trump’s legal team. With the order reinstated, Engoron said, “I intend to enforce the gag orders rigorously and vigorously.”

End of a Diplomatic Era

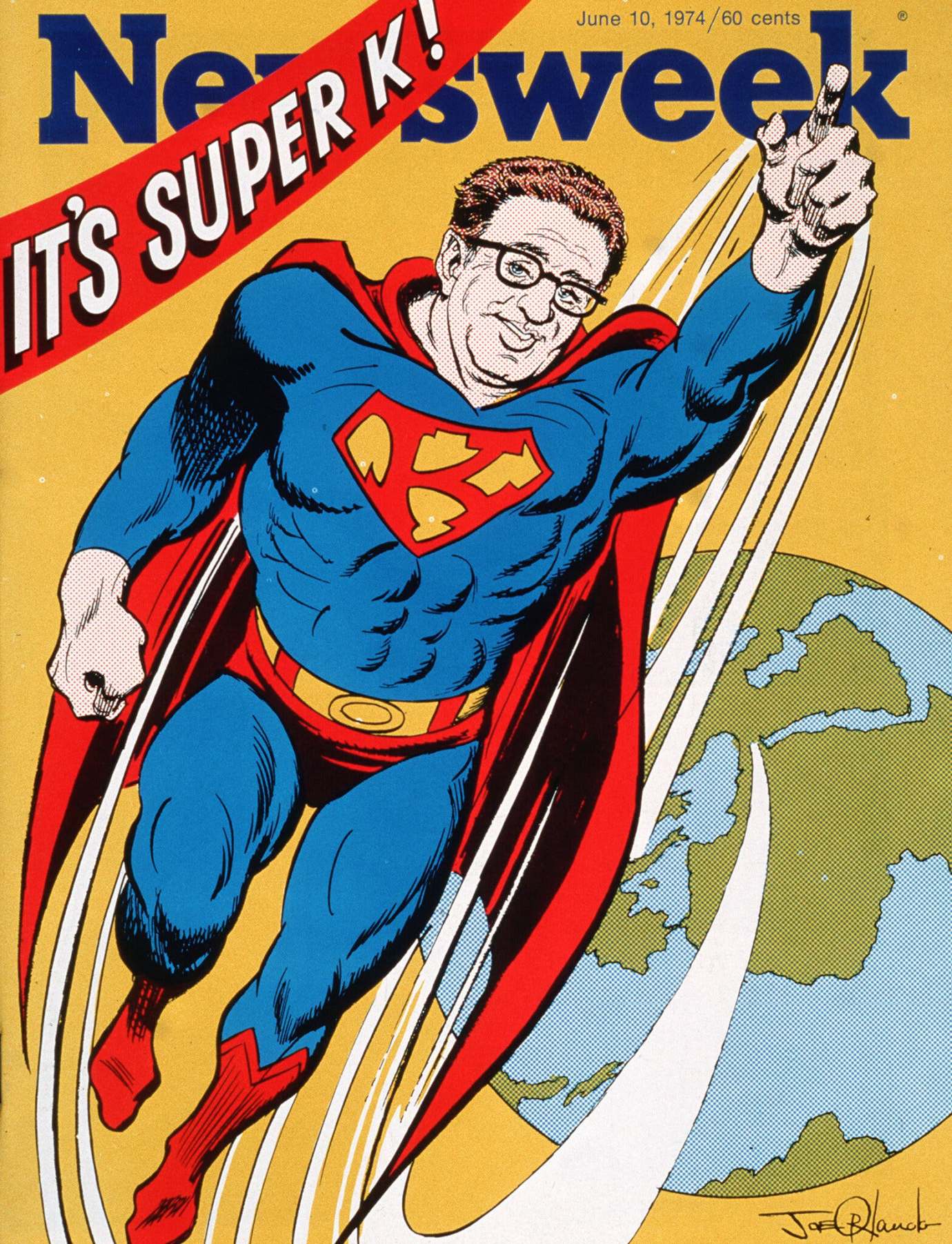

Up in the sky—it’s a bird! It’s a plane! No, it’s Super K—better known as the late Henry Kissinger—on the cover of a 1974 edition of Newsweek magazine!

Kissinger, who died on Wednesday at the age of 100, served as secretary of state in two presidential administrations, and is generally viewed as the most powerful diplomat in postwar American history, working to open China to the Western world and negotiating the United States’ first arms-control deal with the Soviet Union. In addition to playing a pivotal role in brokering the end of the Yom Kippur War—as well as U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, for which he was awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize—Kissinger undoubtedly helped usher in the conclusion of the Cold War. Yet his long career wasn’t without controversy, and he faced fierce criticism—both at the time and later in his life—for his role in decisions to bomb civilians, meddle in the affairs of developing nations, and ignore certain human rights abuses around the globe. Still, Kissinger advised presidents and world leaders up until his final days, and passed away this week as arguably the most consequential diplomatic figure of the 20th century.

Heinz Alfred Kissinger was born into a Jewish family on May 27, 1923, in Fürth, Germany. At the age of 15, he and his family fled Nazi persecution and immigrated to America, settling in New York City. He became a U.S. citizen and served in World War II, deploying to his native Germany as a translator and helping liberate a Nazi concentration camp. After the war, he returned to the U.S. and attended Harvard University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree and a Ph.D. and eventually joined the faculty, where he would remain until he moved to Washington at the invitation of President Richard Nixon.

Kissinger first entered the Nixon administration as the president’s national security adviser in 1969, and was later appointed secretary of state in 1973. He was the first—and so far the only—individual to hold both titles at once, and retained the latter title through Gerald Ford’s presidency. “There is no country in the world where it is conceivable that a man of my origin could be standing here next to the president of the United States,” Kissinger said upon becoming secretary of state. “America has never been true to itself unless it meant something beyond itself. As we work for a world at peace with justice, compassion and humanity, we know that America, in fulfilling man’s deepest aspirations, fulfills what is best within it.”

As his diplomatic star rose during the 1970s, Kissinger’s celebrity grew to near-mythic proportions. Known for his trademark thick-rimmed glasses, gravelly accent, and uncanny ability to surround himself with beautiful celebrities, it was his practice of realpolitik—a diplomatic framework that prioritizes practicality and pragmatism over the advancement of moral or ideological considerations—that made him indispensable in Cold War-era Washington. “He embodied the possibilities and the perils of power, that is him in a nutshell,” Evan Solomon, publisher of GZERO Media and a member of the senior management team of Eurasia Group, told TMD. “Lord Palmerston said, ‘There are no permanent enemies or allies, only permanent interests.’ And [Kissinger] embodied that, and the permanent interests were the interests of the United States.”

Kissinger began making secret trips to China in 1971, a sign of the immense trust placed in him by Nixon. These diplomatic efforts paved the way for Nixon’s own visit in 1972, which helped to draw China out of isolation and instead isolate a growing U.S.S.R—strengthening the U.S.’ hand in the boiling Cold War. The strategy worked, and Nixon was soon invited to visit Moscow—and once again dispatched Kissinger to secretly lay the groundwork for the meeting. Through his diplomacy with the Soviet Union, Kissinger was able to negotiate what he described as “the most important arms control agreement ever concluded.” In May of 1972, Nixon and Soviet Leader Leonid Brezhnev signed the first Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty.

In another success, Kissinger pioneered shuttle diplomacy—in which he served as a traveling mediator between Israel, Syria, and Egypt—to bring the Yom Kippur War to an end, and negotiated lasting ceasefires between the three nations.

Negotiating a graceful exit for the U.S. from the Vietnam War would prove to be a more difficult—and more controversial—task. Much of the challenge lay in balancing two competing priorities: exiting swiftly and preserving the prestige of the U.S. military. He began (characteristically) secret talks in Paris with his North Vietnamese counterpart, Le Duc Tho, while the administration continued to exert military pressure.

In 1973, four years after Nixon entered the White House, Kissinger and Tho reached a ceasefire agreement and the U.S. began to withdraw its troops from South Vietnam. Both men were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize that year—Tho rejected the award, however, on the grounds that he believed peace had not yet been accomplished. The ceasefire was broken shortly thereafter, and by 1975 the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon was captured by North Vietnamese forces.

Kissinger’s secretive nature and single-minded focus on accomplishing what he deemed to be in the national interest—even when it veered into morally dubious actions—invited controversy. “Everything about him had two sides,” said Solomon. “He’d leak, and then he’d wiretap. He’d bomb, and he’d make peace. The guy wins the Nobel Peace Prize for Vietnam, and there’s a case that he broke the law in fighting the Viet Cong and with the bombings of Cambodia. So every part of him had this dual aspect.”

As part of his effort to eradicate communism in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War, Kissinger signed off on a secret strategy to bomb Cambodia, thought to be sheltering communist Viet Cong soldiers and supply lines for the North Vietnamese. The campaign led to the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians, and ultimately created the space for the brutal Khmer Rouge regime to seize power. The bombings were leaked to the press, leading Kissinger to wiretap many of his own staff—an irony, since Kissinger was himself a known and prolific leaker. The war in Cambodia has led some to label Kissinger a war criminal.

Critics have also accused Kissinger of interfering in foreign affairs—or turning a blind eye to foreign atrocities—if it benefited American interests, arguing he too often let humanitarian needs fall by the wayside. “For the first 25 years, in the American Century, America was telling the story and guess what? That story was pretty good,” Solomon told TMD. “But then with the rise of the Global South, as new voices have been let in, people started saying well, you have to cover East Timor, you have to account for Chile. You have to account for Laos and Cambodia. Those folks didn’t have a voice for 20 years in the story. And now they do.”

Still, there’s no simple way to sum up a life that has shaped U.S. foreign policy for more than half a century. “Everyone’s got a hot take on everything now, but having a hot take on Henry Kissinger will get you booted from the serious room,” said Solomon. “There is no hot take on 100 years of Henry Kissinger. It just doesn’t work like that with someone on his scale.”

Kissinger continued to serve as an adviser to presidents throughout the modern era, and remained an active intellectual force even in his twilight years. He co-wrote a book on artificial intelligence with former Google CEO Eric Schmidt in 2021, and just this summer visited China and met with President Xi Jinping—who yesterday mourned the loss of “a good old friend of the Chinese people.” In a letter to Biden, Xi praised Kissinger’s “historic contribution to the normalization of China-U.S. relations with brilliant strategic vision,” and noted that these efforts benefited “both countries as well as [changed] the world.”

Biden himself was more circumspect on Kissinger’s passing. “Throughout our careers, we often disagreed. And often strongly,” he said in a statement released nearly 24 hours after news of Kissinger’s death broke. “But from that first briefing —his fierce intellect and profound strategic focus was evident. Long after retiring from government, he continued to offer his views and ideas to the most important policy discussion across multiple generations.”

For Kissinger critics and promoters alike, his death has sparked its own small-scale culture war—about Kissinger’s role, and the global role of the U.S., in the 20th century and beyond. “Kissinger truly was a guy who, at every moment that he saw the possibilities of using power in its most productive way, always also embodied power at its very worst, and at its most abusive,” said Solomon. “And in a world looking for easy answers and summing up a life, Henry Kissinger does not fit the mold.”

Kissinger, who published three of his own memoirs and spent the majority of his life in the public eye, had certainly given much thought to his own legacy—and when asked to reflect back on his life, would answer with the self-assured confidence that made him so consequential and so vilified. “If I had to do it over again, I would do it again substantially the same way,” Kissinger once told NBC News’ Barbara Walters. “Which may make me unreconstructed, [and] may be one reason why I’m at peace with myself.”

Worth Your Time

- In a piece for Ordinary Times, Andrew Donaldson takes the occasion of Rosalynn Carter’s funeral to explore how our online culture processes mortality. “Death, especially celebrity death, seems to be a starter pistol-like signal for too many to rush to their device and bare the darker corners of their soul because … why?” Donaldson asked. “The person who died, who has no clue who any of these folks are, is dead and can’t respond? Are the online seal claps of a particular in-group some precious resource that can be uniquely mined only as the digital community virtually rallies around the corpse in some sort of viral wake?” Some reactions to the presence at the funeral of Rosalynn’s husband and partner of 77 years highlighted the vacuity of a culture unacquainted with the realities of dying. “When Jimmy Carter was wheeled into his wife’s tribute, suited and covered in a blanket bearing an image of the couple, some on social media reacted poorly,” he wrote. “How, exactly, they expected a 99-year-old man who has been in hospice since February and just lost his wife of nearly 80 years is supposed to look was not addressed. Perhaps many of them have never cared for anyone at the end of natural life. Yes, they don’t look as they once did, they struggle, their mouths hang open, they often can’t communicate effectively, they can’t be as they once were because time is undefeated against presidents or paupers alike.”

Presented Without Comment

Politico: ‘Go F— Yourself!’ Elon Musk Tells Fleeing Advertisers

Also Presented Without Comment

Associated Press: Antisemitic Incidents in Germany Rose by 320% After Hamas Attacked Israel, a Monitoring Group Says

Toeing the Company Line

- In the newsletters: Nick pondered (🔒) how many prominent Republicans will withhold their endorsements from Trump if he is the nominee next year.

- On the podcasts: Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie joined Jamie on The Dispatch Podcast to discuss what foreign policy would look like in his presidential administration, and Sarah, Steve, and Jonah debated the best ways to fix Congress.

- On the site: Kevin examines the life and legacy of Henry Kissinger.

Let Us Know

What are your thoughts on Henry Kissinger’s legacy? Are you glad he had the influence he did for much of the late-twentieth century?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.