Happy Friday! A hearty congratulations to Chicago, Illinois, which placed a better-than-expected #123 in the just-released U.S. News & World Report 150 “Best Places to Live in the United States,” an analysis that compares metro areas across the country. One factor that may have prevented an even more impressive showing? The abysmal performance of Chicago’s sports teams. None of Chicago’s professional teams currently have (MLB) or had this past season (NBA, NHL, NFL) a winning record. (The Blackhawks finished with more losses than any other team in the NHL and the Bears were, once again, the NFL’s worst team.)

The U.S. News analysis doesn’t directly cite Chicago’s embarrassing sports futility as a factor, but context clues elsewhere in the survey support such an inference. Take, for example, the write-up of the best place to live in the U.S.: Green Bay, Wisconsin.

“Home to one of the most storied football franchises in the NFL, the Green Bay Packers, Green Bay has the perfect mix of big-city amenities complemented with a Midwestern, small-town feel.”

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

- The Walt Disney Company announced Thursday it is scrapping a planned $1 billion corporate office expansion in Florida, an apparent escalation of the battle between the Magic Kingdom and Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis. According to a Florida Department of Economic Opportunity estimate, the project would have brought more than 2,000 jobs to the state—with an average salary of $120,000—but a DeSantis spokeswoman claimed it was “unsurprising” a company in dire “financial straits” would cancel an “unsuccessful” venture. The project’s cancellation comes after hints earlier this month from Disney CEO Bob Iger that the company was reconsidering its investments in Florida.

- An FDA advisory panel voted Thursday to recommend approving Pfizer’s Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) vaccine for use in pregnant mothers to protect infants. While the panel unanimously agreed the vaccine was effective, some members raised concerns over the slightly elevated rate of premature births among mothers who received the vaccine in the clinical trial compared to the placebo group. If approved by the FDA—a decision is expected to come in August—the vaccine would be the first to provide RSV protection for infants.

- The Supreme Court on Wednesday denied a request to block two gun laws in Illinois prohibiting the sale of high-capacity magazines and 26 kinds of firearms—including the AR-15 and the AK-47—while challenges to the laws play out in lower court. The National Association for Gun Rights and an Illinois gun store owner are contesting the constitutionality of the laws, and had asked the court for emergency relief while they appeal a federal district court decision.

- Ukraine’s National Anti-corruption Bureau apprehended the chief justice of the country’s supreme court this week and formally arrested him on Thursday. Vsevolod Knyazev is alleged to have accepted a nearly $2 million bribe to rule in favor of a Ukrainian oligarch, and has been charged with graft.

- The New York Times reported Thursday that Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s recent bout with shingles—which kept her out of Washington for nearly three months—was more serious than her office let on. Feinstein developed complications from the infection, including Ramsay Hunt syndrome—which causes facial paralysis and vision impairments—and encephalitis, or brain inflammation. A spokesperson for the senator said the encephalitis had “resolved itself” in March, but the 89-year-old lawmaker appeared visibly weakened and at times disoriented during her first days back on Capitol Hill.

- The National Association of Realtors reported Thursday the median sale price for existing homes in the U.S. was $388,800 in April—down 1.7 percent from April 2022, the largest annual price drop since January 2012. Sales of previously owned homes decreased 3.4 percent from March and were down 23.2 percent year-over-year.

- The Department of Labor reported Thursday that initial jobless claims—a proxy for layoffs—decreased by 22,000 week-over-week to a seasonally-adjusted 242,000 claims last week. The decline reversed the uptick in claims from the previous week—exaggerated by fraudulent claims in Massachusetts—and defied expectations of a cooling labor market.

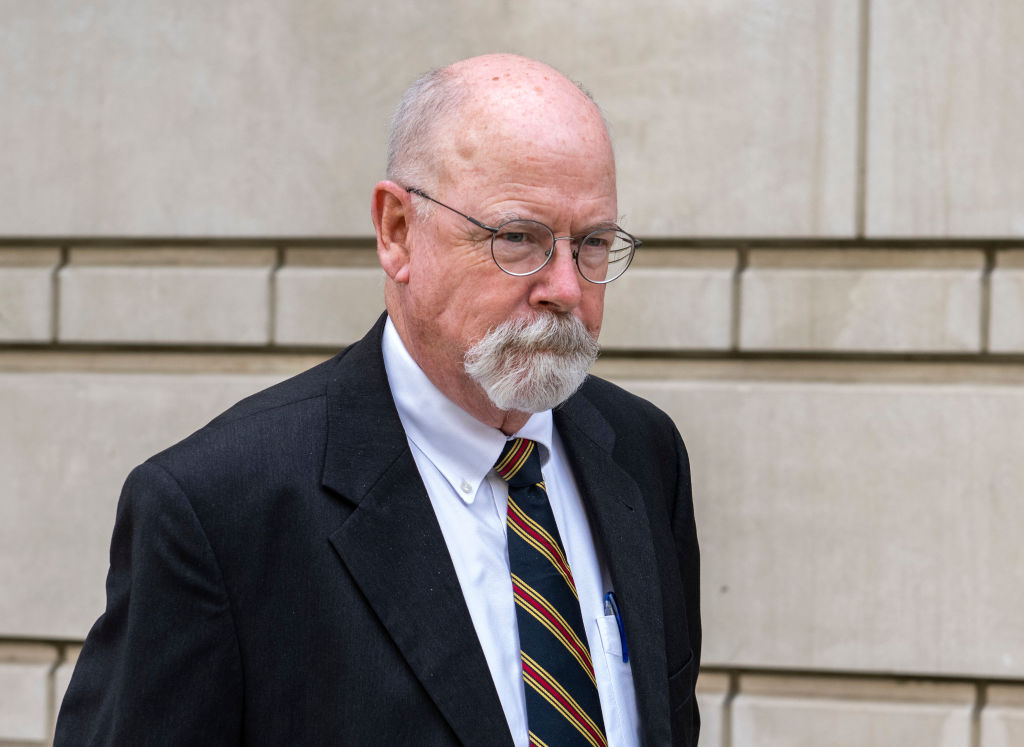

‘Fidelity, Bravery, and Integrity’

Four years and one day after he was first appointed to probe the origins of the Trump-Russia investigation—Operation Crossfire Hurricane—special counsel John Durham’s final report was made available to the public. Did it uncover “the crime of the century?” Was it a “sinister flop” that “ended with a whimper”? Or did it identify numerous instances of unprofessional, incompetent, and prejudiced conduct by federal law enforcement officials that’s incredibly damning for those involved while not necessarily rising to the level of criminality?

If you can’t tell already, we’re leaning towards Door #3.

Within minutes of the 306-page report being released on Monday, a number of progressive commentators had taken to the airwaves to proudly declare there was “no there there” and that Durham had turned in a dud. After all, the special counsel didn’t recommend any additional charges beyond the three he’d already brought, and proposed no “wholesale changes” to FBI or Department of Justice (DOJ) policies or guidelines. But to focus solely on those aspects of the investigation, Durham argued, would be a grave mistake.

“If this report and the outcome of the Special Counsel’s investigation leave some with the impression that injustices or misconduct have gone unaddressed, it is not because the Office concluded that no such injustices or misconduct occurred,” he wrote. “It is, rather, because not every injustice or transgression amounts to a criminal offense, and criminal prosecutors are tasked exclusively with investigating and prosecuting violations of U.S. criminal laws. And even where prosecutors believe a crime occurred based on all of the facts and information they have gathered, it is their duty only to bring criminal charges when the evidence that the government reasonably believes is admissible in court proves the offense beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Many of the report’s key revelations were already in the public domain—through either the DOJ inspector general’s 2019 report, or the three indictments Durham had pursued over the years.

From the inspector general, for example, we learned that the FBI included a number of “significant inaccuracies and omissions” in its applications to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to monitor Carter Page, a former Trump campaign adviser. In August 2020, Durham secured a guilty plea from Kevin Clinesmith, a former FBI attorney who admitted to doctoring an email in 2017 that was used to justify continued surveillance of Page. In September 2021, Durham indicted Michael Sussmann—a lawyer for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign—alleging Sussman lied to the FBI about his motivations for bringing them bogus information linking Donald Trump to a Russian bank. In November 2021, Durham indicted Igor Danchenko—a Russian national living in Virginia and working as a political and intelligence analyst—alleging he lied to the FBI about his role in contributing to the infamous Steele Dossier, an opposition research document paid for by the Clinton campaign that included salacious and untrue information about Trump and his relationship to Russia.

Clinesmith received 12 months probation; Sussmann and Danchenko were both acquitted.

Using those indictments as guideposts, Durham’s final report this week filled in the gaps to present a comprehensive look at just how shoddy federal law enforcement’s work on Crossfire Hurricane truly was. “There is a continuing need for the FBI and the Department to recognize that lack of analytical rigor, apparent confirmation bias, and an over-willingness to rely on information from individuals connected to political opponents caused investigators to fail to adequately consider alternative hypotheses and to act without appropriate objectivity or restraint in pursuing allegations of collusion or conspiracy between a U.S. political campaign and a foreign power,” the report reads. “Although recognizing that in hindsight much is clearer, much of this also seems to have been clear at the time.”

The entire investigation, for example, was kicked off by a cable from Australia, in which diplomats recounted a conversation they had with George Papadopoulos, a low-level Trump campaign staffer. Papadopoulos, according to the Australian diplomats, had made a comment about the Clintons having “a lot of baggage” and suggested the Trump team had heard from Russia about possible assistance with the release of damaging information.

“As an initial matter, there is no question that the FBI had an affirmative obligation to closely examine [this] information,” Durham concludes. But he argues the “raw, unanalyzed, and uncorroborated intelligence” should not have immediately led to a full-fledged investigation into the ongoing Trump campaign—especially without talking more to the Australian diplomats or Papadopoulos. Citing text messages from August 2016, Durham seems to demonstrate that even some FBI officials agreed. “Damn that’s thin,” one agent wrote after asking if there was more to the story. “I know,” another replied. “It sucks.”

The FBI, Durham argues, was far more deferential to Clinton and her team. When the bureau learned in 2014 that a foreign country may try to funnel money to her campaign to curry favor with her, for example, an application for a FISA warrant languished at FBI headquarters for approximately four months, and was only approved on the condition that Clinton received a “defensive briefing,” warning her of the foreign government’s efforts. “No defensive briefing was provided to Trump or anyone in the campaign concerning the information received from Australia that suggested there might be some type of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russians,” the report reads, “either prior to or after these investigations were opened.”

Durham—who was praised by Democrats and unanimously confirmed as the U.S. attorney for Connecticut in 2018—documents several instances of seemingly overt political bias in the report. Peter Strzok—the FBI’s deputy assistant director for counterintelligence when Crossfire Hurricane was launched—repeatedly texted an FBI lawyer about his disdain for Trump, and assured her that the bureau would “stop” him from becoming president. Clinesmith—the FBI attorney who pleaded guilty to doctoring an email—told colleagues “viva le resistance” the day after Trump won the election.

But ultimately, Durham was more concerned about another kind of bias. “It seems highly likely that, at a minimum, confirmation bias played a significant role in the FBI’s acceptance of extraordinarily serious allegations derived from uncorroborated information that had not been subjected to the typical exacting analysis employed by the FBI and other members of the Intelligence Community,” his report concludes. “In short, it is the Office’s assessment that the FBI discounted or willfully ignored material information that did not support the narrative of a collusive relationship between Trump and Russia.”

To many Republicans—whose approval rating of the FBI has fallen from 62 percent in 2014 to just 29 percent last year—the behavior uncovered in the report warranted more than a tut-tut and a few slaps on the wrist. “I’ve never been a reactive ‘lock ‘em up’ type,” GOP Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas tweeted. “But this Durham report is a lock ‘em up moment. We should be looking for statutes that apply to these egregious violations of public trust. If they don’t exist, it’s time we create them so it never happens again.” Steve Bannon, the longtime Trump advisor, labeled Durham’s $6.5 million investigation a “failure” and a “clown show” for not putting anybody behind bars.

But William Barr—Trump’s former attorney general and the man who appointed Durham in the first place—argued these criticisms of the special counsel were unfair. “When you’re dealing with people who make discretionary decisions that were within their authority, it’s very hard to prove corrupt intent,” he said. “If there was a provable crime, it would be brought. John Durham felt he could not prove criminal intent in these cases.” The most common targets of the right’s ire? Strzok, then-FBI Director James Comey, and then-FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe.

The latter—now a CNN contributor after being fired from the FBI—did his best Monday to downplay Durham’s findings. “There is nothing new here,” McCabe told Anderson Cooper. “We knew from the very beginning exactly what John Durham was going to conclude, and that’s what we saw today. We knew from the very beginning this was never a legitimate investigation. This was a political errand to exact some sort of retribution on Donald Trump’s perceived enemies and the FBI.”

But that’s not how the FBI’s current leadership sees it. “The conduct in 2016 and 2017 that Special Counsel Durham examined was the reason that current FBI leadership already implemented dozens of corrective actions, which have now been in place for some time,” the bureau said in a statement released Monday. “Had those reforms been in place in 2016, the missteps identified in the report could have been prevented.”

Durham nods to those updated policies and procedures, but argues that, ultimately, the efficacy of the bureau will come down to the integrity and responsibility of the people working there. “The answer is not the creation of new rules but a renewed fidelity to the old,” he writes. “The promulgation of additional rules and regulations to be learned in yet more training sessions would likely prove to be a fruitless exercise if the FBI’s guiding principles of ‘Fidelity, Bravery, and Integrity’ are not engrained [sic] in the hearts and minds of those sworn to meet the FBI’s mission of ‘Protect[ing] the American People and Uphold[ing] the Constitution of the United States.’”

Supreme Court Leaves Section 230 Alone

The Supreme Court ruled yesterday on cases involving ISIS videos on YouTube and Twitter, and the decision hinged partly on what happened after a gun-toting man named Bernard Welch walked up to a secretary named Linda Sue Hamilton in October 1975 and asked her on a date.

Hamilton moved in with Welch and said she never asked why he disappeared for a few hours every day, or where he got the gold and silver he smelted into ingots in the garage, or what he kept in some 50 boxes in the basement—which turned out to be stolen furs, jewelry, silverware, and antiques. She just did the secretarial work and tracked the sales. But when Welch murdered physician Michael Halberstam during a burglary gone wrong in 1980, a judge found Hamilton liable—she should’ve known, and she helped him even though she didn’t commit the crimes.

Using concepts laid out in the Halberstam case, the Court ruled unanimously Wednesday in two cases—Taamneh v. Twitter and Gonzalez v. Google—that a law allowing lawsuits against parties assisting terrorists didn’t apply to tech companies that failed to remove ISIS accounts from their platforms. By remanding Gonzalez to a lower court with a note that plaintiffs had failed to establish a claim under Section 230, the justices left in place that statute’s liability protection for tech companies—punting what could have been an internet-shaking change.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act stipulates that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Under this statute, tech platforms can moderate content in good faith without becoming a “publisher” and being held liable for what any individual user posts. Gutting this protection, opponents have argued, would either turn social media into (even more of) a cesspool or incentivize or incentivize companies to keep an overly tight rein on what users can post.

The 2016 Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act allows Americans to sue anyone who “aids and abets” international terrorism “by knowingly providing substantial assistance.” In Taamneh, the family of a victim killed in a 2017 attack on a Turkish nightclub sued Twitter, arguing the tech company knew it was hosting ISIS accounts and didn’t do enough to scrub content encouraging terrorism—making it liable for the attack.

But if you think insufficiently rigorous content moderation is a far cry from, say, keeping the books for your burglar lover, you’re in good company—the entire Supreme Court agrees. “Rather than dealing with a serial burglar and his live-in partner-in-crime, we are faced with international terrorist networks and world-spanning internet platforms,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in the unanimous opinion. “Plaintiffs make no allegations that defendants’ relationship with ISIS was significantly different from their arm’s length, passive, and largely indifferent relationship with most users.” Indeed, he noted, plaintiffs didn’t even allege that the attacks were planned using Twitter, making the connection still more tenuous.

Given this distant relationship, Thomas argued holding Twitter responsible for how ISIS used its platform would be more like blaming a postman for the contents of the letter he delivers than the “knowing and substantial” help Hamilton provided Welch. Even the algorithms that boost content to interested users are part of the platform’s “infrastructure,” more a highway Twitter users take to get where they want to go than a friend offering a ride. “Defendants’ mere creation of their media platforms is no more culpable than the creation of email, cell phones, or the internet generally,” Thomas wrote.

The second case decided yesterday—Gonzalez v. Google—had potential to shake up internet norms by undermining Section 230 protections. The plaintiffs were similarly arguing Google had culpability for an ISIS attack because it let the terrorist group post—and even monetize—videos on YouTube, which Google owns. But they took their argument a step further, claiming YouTube’s recommendation algorithm made it a co-content creator alongside the makers of the radicalizing videos it pushed. This threatened the status quo interpretation of Section 230.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle want to reform Section 230—though they disagree on how. And Thomas has previously urged his colleagues to take up a Section 230 case, arguing lower courts may have interpreted the statute too broadly and suggesting in some cases it provides cover for censorship—though narrowing Section 230 in this case could have caused much broader content restrictions. But the Supreme Court justices seemed reluctant to tackle Section 230 during oral arguments in these cases. As Justice Elena Kagan put it: “These are not, like, the nine greatest experts on the internet.”

Sure enough, the justices punted on the question, issuing a three-page order declaring they wouldn’t even touch Section 230 and sending the case back for lower court review with the suggestion it wouldn’t survive the terrorism claim standard. Points to Alan Rozenshtein, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, who predicted this in February when we covered oral arguments. “What they may choose to do is rule in favor of Google and Twitter, but on the grounds that, even if Section 230 doesn’t apply, they’re just not liable under the terrorism statutes,” he said then. “That would allow them to avoid the 230 issue altogether.”

The decisions don’t necessarily slam the door on any future reworking of Section 230 protections, though, as details of these specific cases—such as terrorists not using Twitter or YouTube to plan the relevant attacks—rendered the plaintiffs’ arguments weaker than future claims might be. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson suggested as much in a concurring opinion. “Today’s decisions are narrow in important respects,” she wrote. “Other cases presenting different allegations and different records may lead to different conclusions.”

But for a Supreme Court that’s recently been upending abortion law and regulatory regimes, the decision is a bit anticlimactic—and you won’t hear tech company supporters complaining. “This is a huge win for free speech on the internet,” said Chris Marchese, litigation center head for NetChoice, a tech trade group which represents Twitter and Google. “The Court was asked to undermine Section 230—and declined.”

Worth Your Time

- Aleksander Kulisiewicz, a survivor of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, dedicated his life to preserving the music of the Nazi camps. In an excerpt from a forthcoming book, Makana Eyre documents Kulisiewicz’s extraordinary efforts. “By the time the surviving prisoners of Sachsenhausen were liberated in early May 1945, he had committed hundreds of pages of camp music to memory, including 54 of his own compositions and [Rosebery] d’Arguto’s elegy for Europe’s Jews, ‘The Jewish Deathsong,’” she writes. After the war, Kulisiewicz expanded his work, interviewing survivors throughout Europe about the music in the other camps. “The more people he interviewed, the clearer it became that deportees across the Nazi camp system had turned to music to cope and survive, just as he and d’Arguto had done at Sachsenhausen,” Eyre explains. “At camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Majdanek and Dachau, inmates had gathered to share music and poetry. Some prisoners composed original scores, from popular songs to classical or modern music, many of true artistic quality. Others wrote new lyrics to melodies they knew by heart.” By the end of his life, Kulisiewicz had amassed “one of the most complete archives of music and music-making in the Nazi camps anywhere in the world.”

Presented Without Comment

Reuters: Pentagon Accounting Error Overvalued Ukraine Weapons Aid by $3 Billion

Also Presented Without Comment

San Francisco Chronicle: Celebrity Chef’s New Bay Area Restaurant Exempt From Local Gas [Stove] Ban

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Politico: Pence Lifts Words Directly From Old Trump Speech

Toeing the Company Line

- In the newsletters: Nick argues the 2024 Republican presidential primary will not be a repeat of the 2016 Republican presidential primary.

- On the podcasts: Sarah, Steve, and Mike discuss the Durham report, the debt ceiling, and AI.

- On the site: Drucker takes an exclusive first look at New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s prospective presidential run and Charlotte examines how the embattled Ukrainian city of Bakhmut became the center of Russian infighting.

Let Us Know

Did Durham’s report change your mind about anything? What do you think the FBI should do—if anything—to win back the trust it’s lost among Republicans?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.