Happy Tuesday. In accordance with the usual hurry-up-and-wait flow of Congressional action, we’ve got a full slate of legislative stuff to break down as the Senate plans to go to recess as early as next week. Let’s get right to it.

Crashing Through the Debt Ceiling

It’s been a while since Congress had its last regularly scheduled fight over the debt ceiling, but it’s about that time again now. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 suspended the debt ceiling entirely for a period of two years—a move that proved fortuitous, given the titanic pile of pandemic spending that lurked just around the corner. Over the weekend, however, that provision expired—automatically snapping the debt ceiling to the current level of debt and putting Congress on a short clock to raise the ceiling again.

As a matter of law, Congress decides how much money comes into and out of the hands of the federal government when it passes tax and spending bills. When tax revenues aren’t large enough to cover the spending Congress has authorized—which, in modern times, is always—the Treasury Department raises the difference by issuing bonds to borrow the rest. But the Treasury can only do this up to the limit prescribed by Congress—the federal debt ceiling. As total borrowing approaches the debt ceiling, Congress faces pressure to raise the limit, since the alternative—for the United States government to default on its bills—would risk financial catastrophe.

That catastrophe hasn’t arrived yet: The Biden administration has the ability to utilize accounting tools and emergency funds, called “extraordinary measures,” to pay the government’s bills and keep the country from going into default. But these measures are not inexhaustible, and at most can tide the government over for two or three months.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has been sounding the alarm on the Hill for weeks on this issue, to little discernible effect. In a letter to lawmakers in mid-July, she said the consequences of not raising the debt ceiling so that the federal government can pay its bills would be dire: “Failure to meet those obligations would cause irreparable harm to the U.S. economy and the livelihood of all Americans.”

Far from bringing the issue to the floor for quick resolution, however, Congress blew past the deadline with something of a collective shrug. (Granted, they were otherwise occupied: see the end of the newsletter for an update on infrastructure reforms.)

Experts and lawmakers told The Dispatch that Congress will raise the debt ceiling this fall. It’s a question of when exactly, how they’ll pass it, and who will vote in support of the move.

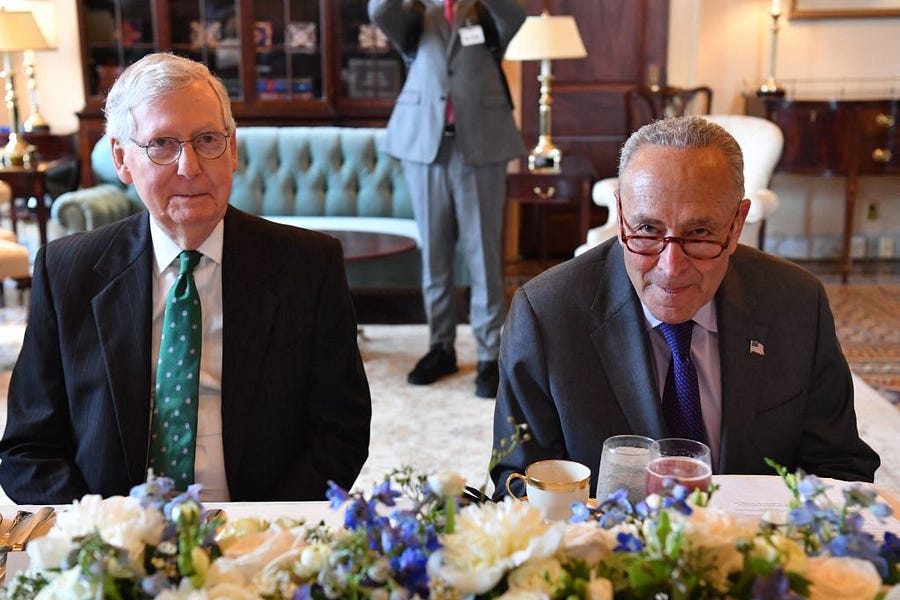

So far, Republican messaging has been that raising the ceiling is not their problem. Instead, they’re using it as an opportunity to slam Democrats for the big spending coming out of Washington. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell told Punchbowl News last month that “I can’t imagine there will be a single Republican voting to raise the debt ceiling after what we’ve been experiencing … this free-for-all for taxes and spending.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer in floor remarks Wednesday called McConnell’s position “shameless, cynical, and totally political.”

“This debt is Trump’s debt,” Schumer said. “It’s [COVID-19] debt. Democrats joined three times during the Trump administration to do the responsible thing, and the bottom line is that Leader McConnell should not be playing political games with the full faith and credit of the United States. Americans pay their debts.”

Sen. Jon Tester, a Democrat from Montana, told The Dispatch Thursday that Republicans’ stance is “playing Russian roulette with our economy.” Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, told The Dispatch that “it’s a question of responsibility … we have to pay our bills.”

Some experts argue that fiscal-responsibility arguments against raising the debt ceiling are barking up the wrong tree. Ben Ritz of the Progressive Policy Institute told The Dispatch that the debate “is not how much money to put on the credit card. It’s just debating how much of the bill to pay when it comes due.”

Still, McConnell’s position is not surprising.

“Historically the way debt limits have worked [is that] when there is unified government, the party in power basically has the responsibility to raise it and the party that is not in power sometimes provides a few votes but generally votes against it,” Marc Goldwein, senior vice president at the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said.

At the end of the day, Goldwein said, lawmakers have always found a way to raise or suspend the debt ceiling.

The United States last came closest to defaulting on its debt in 2011. House Republicans’ standoff with then-President Barack Obama over the issue roiled financial markets and led to a reduction in the U.S. credit rating.

“The past decade Republicans have raised the debt limit pretty easily,” said Brian Riedl, an economic policy expert at the Manhattan Institute, although there was “a bit of a backlash to how close we came to default in 2011.” He also noted that the debt ceiling was far from a central concern of Republicans during the free-spending years of former president Donald Trump.

Democrats were not always easy “yes” votes themselves on debt ceiling increases. As a Senator, Barack Obama voted against a debt ceiling raise in 2006 when it came up during the George W. Bush administration.

So far, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Schumer have not publicly settled on how they will deal with the issue.

“We’re considering all options,” Pelosi told Bloomberg News at the beginning of July.

Democrats have several options. They could choose to tee the debt ceiling increase up as a standalone vote. But this option is unlikely to be popular, particularly among moderates in tough districts. Necessary or not, the perennial raising of the debt ceiling is a regular reminder that Congress regularly fails to spend within its means, and voting to raise the ceiling is sometimes seen as giving the government permission to maintain the deficit spending status quo.

Alternatively, Democrats could fold a debt ceiling increase into the massive “human infrastructure” reconciliation bill they intend to pass later this year on a party-line basis. Folding it in with a larger package would allow members to more easily justify the vote by pivoting from the bad news of the debt to the good news of what the bill’s spending is intended to accomplish. But this approach too has its risks: As we’ve covered in Uphill, it’s not a slam dunk that Democrats will be able to pass their reconciliation bill at all, given their miniscule margin of error in both the House and Senate.

Democrats could also seek to address the debt limit as part of some other bill, such as the bipartisan infrastructure bill or must-pass government funding bills at the end of September. If they do take that route, they would likely have to find some way to woo Republicans via compromise reforms.

Some Republicans have expressed an openness to pairing a vote for the debt ceiling hike with fiscal reforms.

According to a Republican Study Committee memorandum published in June, some of the reforms GOP members might push for include demanding any increase of the debt limit be offset by cuts elsewhere and capping non-defense spending. But the document warned against pairing a debt limit increase with “must pass” spending legislation.

Sen. Rick Scott of Florida told The Dispatch he would support a bill raising the debt ceiling in exchange for implementing significant new budgetary constraints, such as requiring a two-thirds majority of the Senate to authorize new deficit spending in years when debt has already exceeded 100 percent of GDP. Sen. Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania said he would consider voting for an increase “if there’s a commitment to make some structural reforms that will move us toward a direction of being fiscally solvent.” But he added that as far as he knows, Democrats are not yet huddling with Republicans to have conversations about any of these reforms.

“I think people are starting to get a level of uneasiness, on the right at least, with the level of spending,” Brendan Buck, who served as an aide to GOP House Speakers John Boehner and Paul Ryan, told The Dispatch. But he added that the strength of fiscal hawks in the Republican party has lessened in recent years. “As with everything, you can’t ignore Donald Trump’s impact on this. He showed no interest in cutting spending and in fact was quite a large government Republican … if the president isn’t going to lean into fiscal discipline … Republicans are going to follow along.”

Light at the End of the Infrastructure Tunnel

After a full weekend of work from senators and their staff, the bipartisan infrastructure bill—a 2,702-page document officially titled the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act—was released Sunday night.

The bill focuses on hard infrastructure projects across the country, from simple highway improvements to funding for fishing and boating projects.

The total cost comes to $550 billion of new spending over five years, a large chunk of which—around $110 billion— will be set aside for roads, bridges, and other “major projects.” The bill also appropriates $73 billion for energy projects, $66 billion for the country’s rail systems, $65 billion for broadband internet access, $55 billion for water infrastructure, and many other projects.

Speaking from the Senate floor Sunday night, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said he hoped the bill’s passage through the Senate would be relatively painless: “Given how bipartisan the bill is and how much work has already been put in to get the details right, I believe the Senate can quickly process relevant amendments.” Schumer also reiterated his commitment to advance Democrats’ multi-trillion “human infrastructure” package immediately following the bipartisan bill; what all will be in that package remains to be seen.

Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who unlike Schumer is not champing at the bit to get to “human infrastructure,” is correspondingly in less of a hurry to rush through passing the bipartisan bill.

“I’m confident that out of the 100 of us who serve in this body, 100 will be able to find parts of the legislation that we wish were different,” McConnell said Monday. “Our full consideration of this bill must not be choked off by any artificial timetable that our Democratic colleagues may have penciled out for political purposes.”

Getting to “human infrastructure” isn’t the only timing consideration in play: The Senate is currently scheduled to go on recess starting August 9. It’s Schumer, however, who sets the Senate calendar, and threatening to keep lawmakers cooped up in Washington is a time-honored way for leadership to grease a bill’s skids. “We’re going to stay here as long as it takes to get this done,” the majority leader said today. “Period.”

But the legislative schedule got a little more complicated on Monday afternoon after Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina announced he had tested positive for coronavirus. Graham, who is one of the Republican senators in the bipartisan infrastructure group, will now have to quarantine for ten days. The Senate does not have a proxy voting system, so that leaves the bill with one less “yes” vote than it had heading into the week.

Further complicating the situation is the fact that Graham joined a number of bipartisan senators on Sen. Joe Manchin’s houseboat for a party over the weekend. All senators who were on the boat are getting tested for coronavirus, and so far Graham is the only one to receive a positive result. Manchin told reporters the houseboat party was all outdoors and everyone in attendance was vaccinated.

Something Fun

Of Note

We hope you are enjoying Uphill. To ensure that you receive future editions in your inbox, opt-in on your account page.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.