Editor’s Note: Thanks for reading today’s edition of Capitolism! It’s landing in your inbox later than usual because Scott has been busy delivering testimony on Capitol Hill. Read on to find out what he’s telling members of the Joint Economic Committee.

Before we begin, a sad note: Last week we lost David Boaz to cancer at the much-too-young age of 70. For those who don’t know or know of David, he spent over four decades as the Cato Institute’s executive vice president—a title that doesn’t come anywhere close to reflecting his immense influence on not just Cato and libertarianism, but also American public policy and human liberty here and abroad. He was also just a really good guy, and he’ll be sorely missed. You can read more about David’s life and work—along with far better tributes than mine—at the dedicated web page Cato set up in his honor. (The tribute video is particularly excellent.) RIP.

Anyway, the content of today’s newsletter will be a bit different from the usual because of major time constraints mainly due to two different congressional hearings I took part in over the past week. (I’m so very popular.) So, you’re getting a truncated version of the second testimony, which—depending on when you open these emails—I might actually be giving to the Joint Economic Committee right as you’re reading this. I’ll cover some ground we’ve already explored here but also a lot of new—or at least updated—stuff too. Even if you’re a Capitolism diehard (as you all obviously are), there’s almost certainly some worthwhile nuggets in here. And for those who still don’t think you’re getting your money’s worth, don’t fret: Capitolism will return to “normal” next week.

So, with that longwinded excuse for mailing-it-in out of the way, let’s get on with the show.

The Industrial Policy Mirage

Industrial policy is back in Washington. Not only do its supporters claim that it can bring about a market-beating manufacturing renaissance for critical industries, they insist this renaissance has already begun. I’m skeptical for a few reasons.

First, while domestic investment in manufacturing and related construction has increased substantially, it must be put into context. Both demand for and onshore investment in goods targeted by new U.S. industrial policy were increasing before its enactment, and recent increases in related private spending are still a relatively small share of U.S. economic output. Actual U.S. manufacturing performance, meanwhile, remains subdued.

Second, we must also consider the actual return on the investments. When the government showers preferred companies with trillions of taxpayer dollars and numerous restrictions on foreign trade competition, its policies will inevitably produce something in the real economy. The question is what, exactly, all that government support is getting us.

If, for example, the policies generate hundreds of billions of dollars in private manufacturing investment that eventually translates into dozens of vibrant, innovative, and globally competitive American factories and a sterling U.S. economy, then the federal government’s gamble will have paid off. Conversely, declarations of policy victory today will look foolish in retrospect if all that government spending results in a few such successes but as many or more failures—not just a few empty fields or moribund facilities but entire companies and industries that depend on continuous government protection or support—and myriad unintended or unseen costs in the broader U.S. economy.

It’s too early to say definitively what a new U.S. industrial policy will produce. However, there are already signs that the subsidies and protectionism supposedly fueling a U.S. manufacturing “boom” are encountering problems both domestically and internationally—counterproductive, expensive, and largely preventable problems at that.

Putting the ‘Boom’ in Context

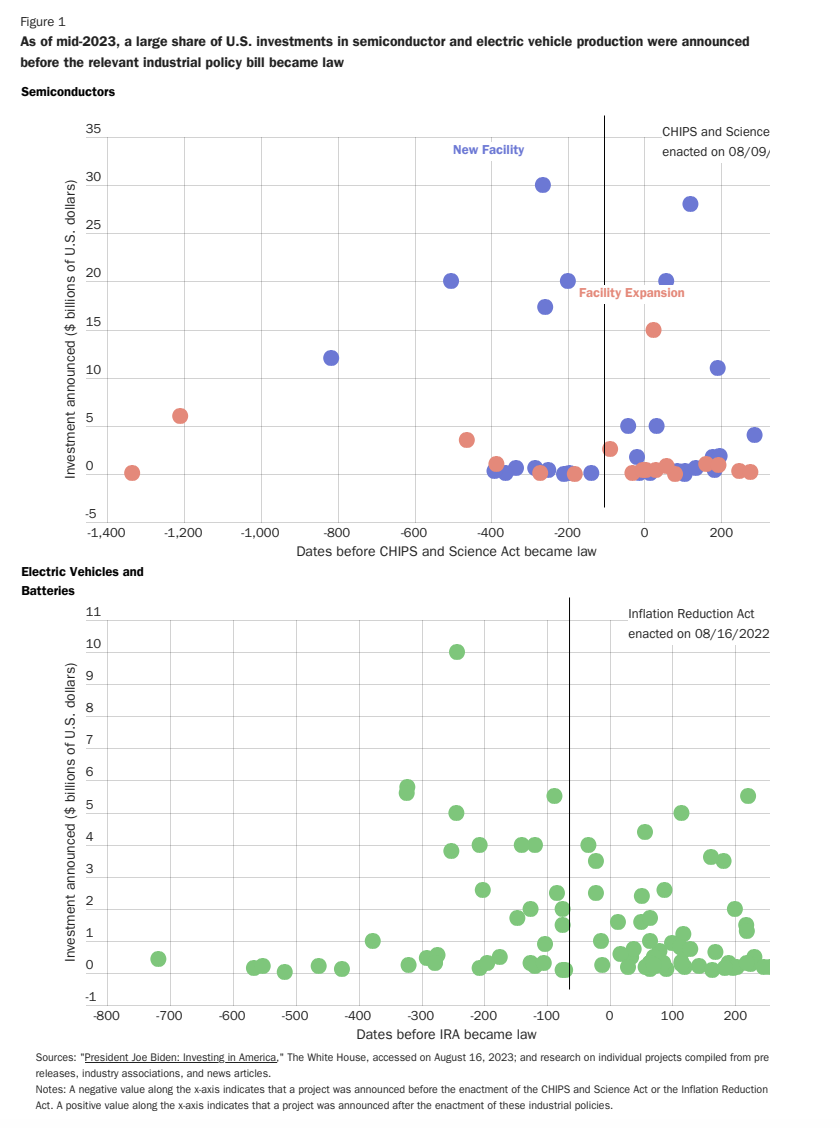

Let’s first put recent increases in both manufacturing investment and construction spending in proper context. For one thing, it’s unclear just how much of these gains have been caused by, instead of merely coincident with, new U.S. industrial policies. To take two examples, before the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS and Science Act became law, the pandemic, geopolitics, and other factors had already increased companies’ interest in diversifying semiconductor sourcing, and private demand for and investment in green energy was already soaring. Moreover, a large share of major U.S. semiconductor and EV investment announcements trumpeted by the White House came months or even years before CHIPS and the IRA became law:

It’s possible that some of these early announcements were made in anticipation of new U.S. subsidies or tariffs, but many—if not most—probably weren’t. Even as late as July 2022, climate-related incentives in the IRA were considered off the table due to insufficient votes in the Senate, and the CHIPS Act also faced uncertainty until the very end. It’s therefore reasonable to conclude that a nontrivial portion of the manufacturing investments that occurred before (or even shortly after) these bills passed Congress were not owed to the policies themselves.

Regardless, manufacturing investments are still a relatively small share of total private investment, and they’re an even smaller share of total economic output. Real private fixed investment in manufacturing structures in Q1 of 2024, for example, was $147.6 billion (in chained 2017 dollars) and thus accounted for only 3.6 percent and 0.6 percent of total private fixed investment ($4.1 trillion) and Real Gross Domestic Product ($22.7 trillion), respectively, recorded during that same quarter. And as the Treasury Department noted last year, total inflation-adjusted construction spending in the United States through April of 2023 was actually below levels seen in 2019 and early 2020.

Thus, while manufacturing investments might someday be important for the U.S. manufacturing sector, they are not the current economic game-changers that they’re often made out to be.

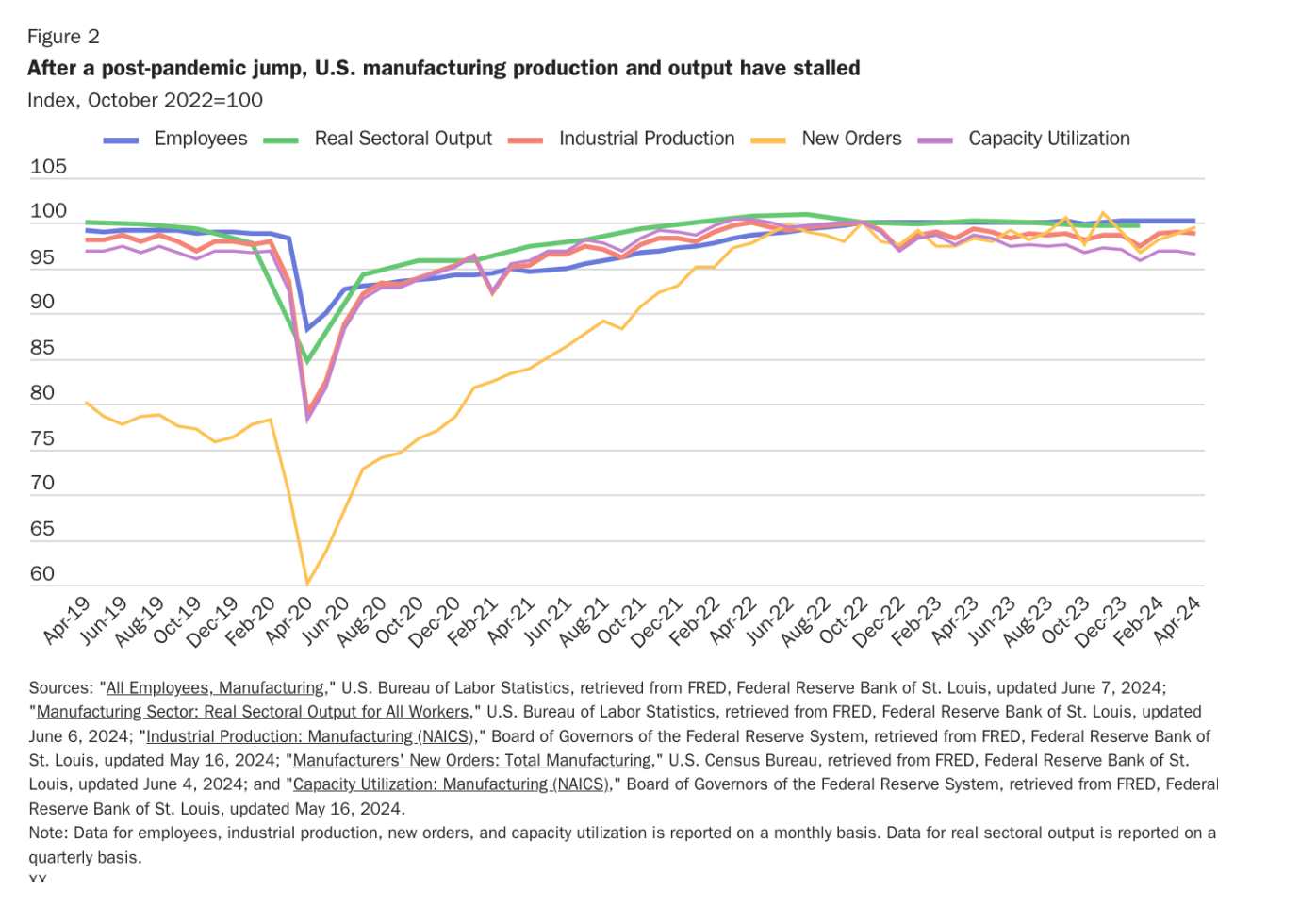

In the meantime, the actual U.S. manufacturing sector—i.e., the one producing goods and hiring manufacturing (not construction) workers today—has stagnated, thanks to higher interest rates, continued materials inflation, worker availability, economic uncertainty, tariffs and trade disputes, and other headwinds. Total U.S. manufacturing employment, output, orders, and capacity utilization have been basically flat since Fall 2022 (i.e., right after the IRA and the CHIPS Act were signed into law).

Private surveys show similar trends. The latest Institute for Supply Management’s private survey of manufacturing purchasing managers (aka the “Manufacturing PMI”) sat at 49.2 percent—a contraction in economic activity that followed one month of expansion and 16 consecutive months of contraction before that, dating back to September 2022. The National Association of Manufacturers latest (Q1 2024) Manufacturers’ Outlook Survey, meanwhile, found that 68.7 percent of respondents felt “either somewhat or very positive about their company’s outlook”—“the sixth straight reading below the historical average of 74.8%.”

Industries such as semiconductors and transportation have performed better in recent months. But, so far at least, the United States is witnessing less a “manufacturing boom,” and more the possible formation of a two‐tier industrial economy. In Tier One are large companies in industries preferred by the government and, to a lesser extent, reshoring operations because of pandemic‐related and geopolitical uncertainties. According to various reports, these firms are investing, more optimistic, and, theoretically at least, poised to grow in the future. In Tier Two, however, are many existing American manufacturers, especially smaller ones and ones not targeted for government support, that are weaker and more pessimistic. Their future remains more in doubt.

Perhaps a broad, nationwide “boom” will materialize in the future. But it’s just as likely—if not more so—that we are again seeing what critics of targeted tax credits, subsidies, and tariffs have long cautioned regarding these types of policies (i.e., that they do not expand the overall economic pie in the United States or generate sustainable, long-term growth, but instead simply redistribute existing resources like money, materials, manpower, etc., to favored companies at a net loss to the overall U.S. economy). This unfortunate outcome is especially concerning today, absent significant tax, regulatory, trade, immigration, and other supply‐side reforms that would allow total national output to increase in response to stimulus-fueled demand—reforms that American manufacturers, including in government-preferred industries, are expressly seeking.

Early Warning Signs in the United States

It is too early to definitively judge new U.S. industrial policies, but recent developments in the United States give us at least four reasons to be concerned about whether they’ll pay off.

First, the costs of building, staffing, and starting production within subsidized facilities has increased substantially—thanks in large part to U.S. policy. Part of the cost increase is owed to macroeconomic factors, as well as U.S. government subsidies further boosting demand for a limited supply of construction goods, services, and equipment. But it is also the result of new U.S. industrial policies colliding with longstanding supply-side constraints (which are often caused or exacerbated by other federal policies). For example, long environmental impact assessments, litigation under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and other permitting restrictions have delayed or scuttled U.S. wind and solar projects and related domestic manufacturing. Restrictions on legal immigration are contributing to subsidized firms’ difficulties in finding workers to build and operate new facilities, especially for high-tech manufacturing. Tariffs, “Buy American” provisions, trade remedies duties, and other U.S. trade restrictions inflate the cost of construction materials and manufacturing inputs.

For these and other policy-related reasons, many subsidized manufacturing projects’ costs have increased substantially, and even advocates have recently worried that existing supply-side impediments threaten U.S. industrial policies’ implementation and efficacy. As the former director of the White House National Economic Council Brian Deese just wrote, he and his colleagues “underestimated just how big a barrier [regulations] would pose to clean-energy adoption” and the IRA itself—even though many experts had warned of these very problems long before the IRA became law.

Second, higher costs, changing market conditions, and other unforeseen issues have caused many announced U.S. manufacturing projects to be delayed or canceled outright, some after companies had already spent significant sums on initial siting and construction. For example, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has delayed production at its first semiconductor facility in Arizona (announced before the CHIPS Act became law) from 2024 to 2025, while delaying its second plant from 2026 to 2028. Numerous EVs and battery projects have also experienced delays and cancellations. Finally, Bloomberg reported last month that, less than two years after the IRA “unleashed a $16 billion flood of promised investments in solar manufacturing” (and despite numerous tariffs on imported solar modules and cells), “manufacturers have quietly shelved or slowed plans for at least four of those plants”, including Enel SpA in Oklahoma, Mission Solar in Texas, CubicPV in Massachusetts, and Heleine in Minnesota.

Surely, not every subsidized and protected U.S. manufacturing investment is experiencing such difficulties, but these and other episodes nevertheless remind us that a wide and uncertain chasm lies between investment announcements and construction starts on the one hand and actual, functioning production facilities on the other. They also highlight the risk of industrial policies imposing not only significant budgetary costs but also numerous unseen costs, including higher consumer prices (where higher costs are passed on) and the diversion of taxpayer and private resources away from more productive and timely U.S. endeavors.

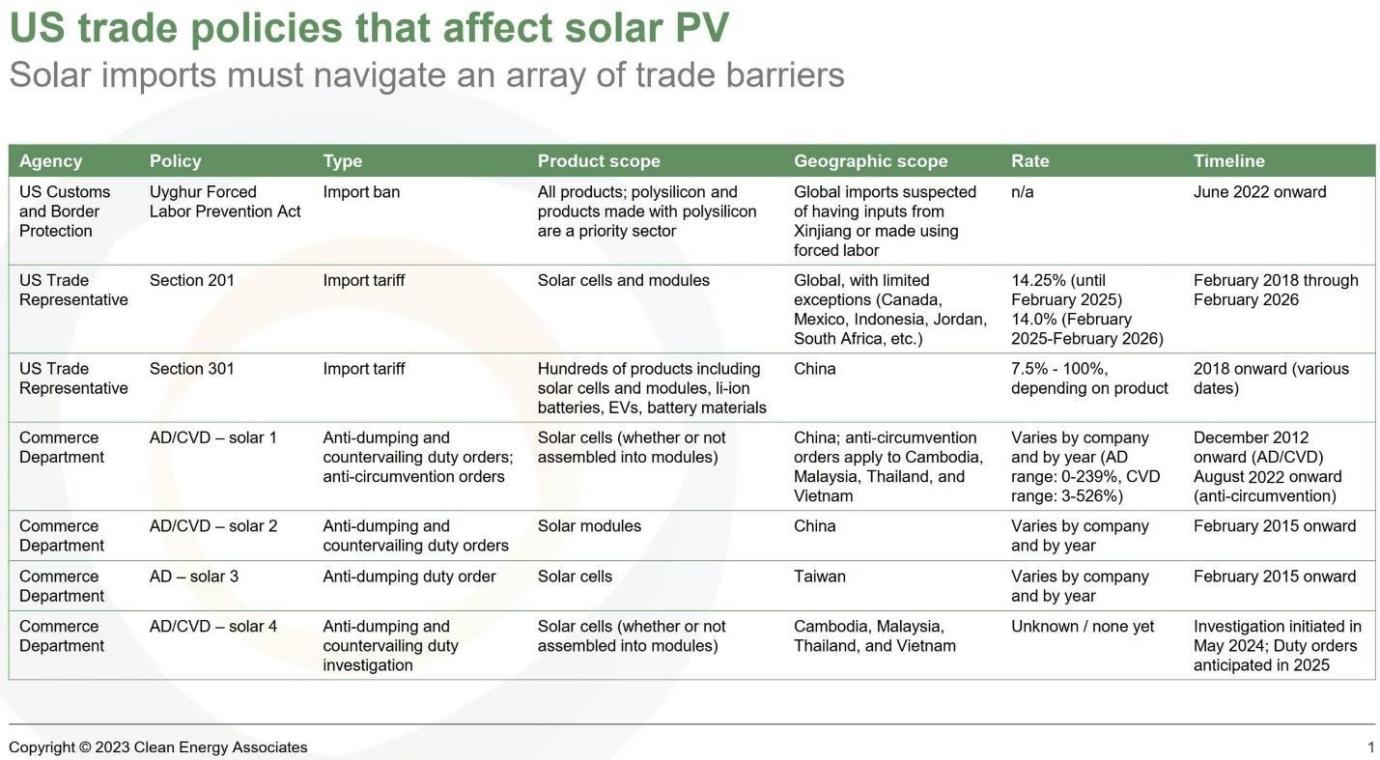

Third, there are already signs that at least some of the U.S. factories eventually completed might not produce innovative technologies that can compete in a global marketplace without open-ended government support. For example, even with numerous import restrictions and “hugely lucrative” IRA subsidies, BloombergNEF estimates that “US-made solar cells and modules will cost 18.5 cents a watt, compared with 15.6 cents for a product from south-east Asia.” Thus, U.S. solar producers recently filed yet another petition for import protection—the seventh such action since 2012.

New U.S. semiconductor facilities raise similar competitiveness concerns. TSMC’s first Arizona facility will produce 4-nanometer chips in relatively small volumes (20,000 wafers per month) when it begins commercial production in mid-2025, but the company is already producing 3-nanometer chips in Taiwan in much larger volumes (100,000 wafers/month this year) and intends to begin mass producing 2-nanometer chips there next year. Samsung is doing something similar with its factories in Texas and Korea, and both companies promise they’re keeping the most bleeding-edge technology at home.

Finally, recent articles on the state of Chinese EV production suggest that U.S. producers’ vehicles are lagging not just in price, but also in quality and innovation. President Biden imposed high tariffs on these vehicles in the hopes that American automakers can catch up.

As I have documented, however, there are strong economic and historical reasons to suspect that solar, EV, semiconductor, and other government-supported industries will not become efficient, innovative, and globally competitive enterprises in the years ahead. There is also a serious risk that, instead of letting struggling industrial policy projects fail, U.S. policymakers will be tempted to keep them afloat with more subsidies and protectionism, and that American consumers and the broader U.S. economy and environment will suffer as a result.

Fourth, we have strong reasons to worry that politics will undermine industrial policies’ implementation and efficacy—a common problem for such measures, especially in the American political system. The Biden administration has conditioned receipt of CHIPS subsidies on applicants fulfilling certain social conditions—such as providing care for the children of workers; implementing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiatives; and paying construction workers local “prevailing wages,” as defined under the Davis-Bacon Act—that will inevitably raise chipmakers’ costs..

Bureaucratic delays and confusion have also materialized. For example, the EV transition requires the availability of a vast network of charging stations, yet despite Congress previously agreeing to spend $7.5 billion to deploy thousands of chargers, not a single charger had been installed through this program by the end of 2023, with state governments and the industry blaming “the labyrinth of new contracting and performance requirements they have to navigate to receive federal funds”. Meanwhile, the eligibility of EV models for the IRA’s tax credits has changed multiple times as the Treasury Department has modified the relevant rules.

Political uncertainty and partisanship also threaten industrial policies’ ability to incentivize long-term investments in the United States. Given the differing positions taken on climate by the presumptive candidates for this year’s presidential election, firms cannot know whether at least some of the incentives currently available to them could be rolled back. An analysis by Wood Mackenzie reports that a change in administration come November would risk $1 trillion in investments in the U.S. energy sector.

In sum, even if we assume that new industrial policies have caused most of the recent increase in U.S. manufacturing investment, many questions remain as to whether this spending will ultimately result in thriving domestic semiconductor, EV, and other industries and thus justify the industrial policies’ exorbitant seen and unseen costs.

Many signs, in fact, point to the opposite conclusion.

Bring on the Global Subsidy Race (and Future Trade Disputes)

Recent U.S. industrial policy also raises concerns internationally. Subsidies here have prodded Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the European Union, India, and other countries to offer subsidies of their own, while encouraging the Chinese government to double- or triple-down on its recent industrial policy schemes. Since the CHIPS Act was passed, for example, governments have offered more than $300 billion in grants, loans, tax credits, and other supports to keep or attract semiconductor investments. The IRA fomented a similar reaction abroad.

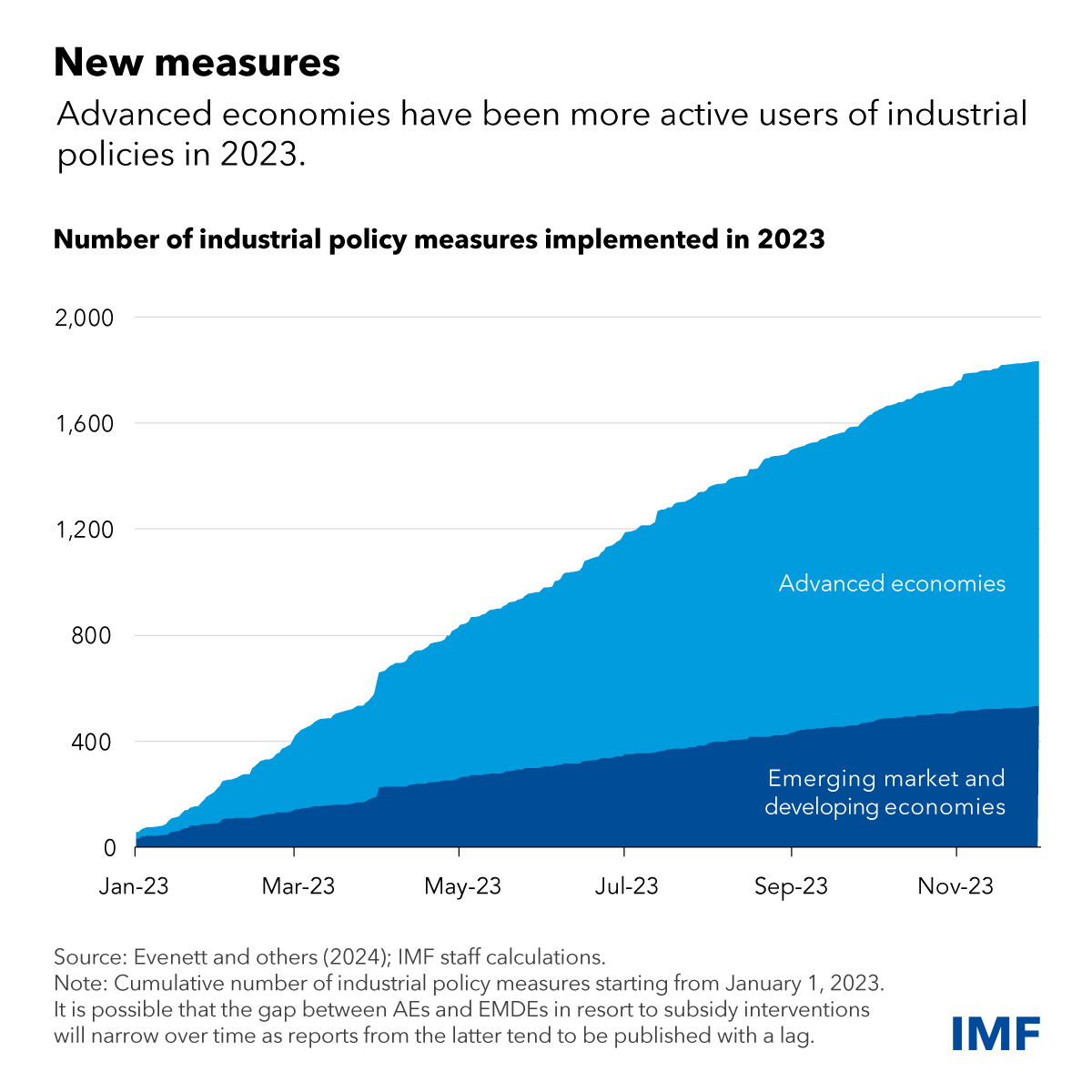

Overall, experts at the International Monetary Fund and the organization Global Trade Alert, which tracks nations’ use of industrial policy and related measures, have found a dramatic global increase in such measures in recent years—more than 2,500 last year alone. They further concluded that this wave was “primarily driven by advanced economies” like the United States, with subsidies “the most employed instrument.”

This recent trend is again unsurprising, as subsidy races are common throughout history. In fact, Global Trade Alert previously examined governments’ subsidy awards since 2008 and found that new measures in one economy were typically followed by similar subsidies in another economy just six months later.

Today’s uncoordinated and predictable “subsidy race” raises several concerns. First, it could offset or even undermine the very domestic investments that the U.S. industrial policy is trying to encourage. Semiconductor subsidies, for example, were largely justified on the grounds that the United States’ share of global chipmaking has declined substantially in recent decades. However, Boston Consulting Group estimates that the semiconductor “building boom” here will—optimistically assuming everything announced actually gets built—boost the U.S. share of global chip production from 12 percent in 2020 to just to 14 percent in 2032, largely because other governments are also stepping up their own spending on these industries.

Furthermore, rampant government subsidies raise a serious risk of global overcapacity that would collapse prices and put U.S. and foreign producers of subsidized goods in serious financial distress. In fact, there are already signs that the global semiconductor, solar panel, EV, and battery markets are reaching a point of saturation (or worse). Should global gluts materialize and persist, domestic manufacturers in the United States and other jurisdictions could request government protection from foreign competition, via “trade remedy” measures (i.e., antidumping or countervailing duties) or other import restrictions. This common move, in turn, could spawn retaliatory actions here and abroad, not only exacerbating economic losses from tit-for-tat protectionism but also raising diplomatic and geopolitical tensions with allies and challengers alike. In the end, almost everyone—consumers, producers, investors, etc.—would be worse off.

The risk of U.S. industrial policy encouraging subsidy races and trade conflicts is not merely theoretical. As I have documented in several papers and columns, this very scenario has played out numerous times throughout U.S. trade policy history—including in automotive goods and semiconductors in the 1980s and 1990s and solar panels today. Similar problems are not guaranteed to unfold in other industries in the future, but we shouldn’t be surprised if they do.

Second, subsidy races and trade conflicts can significantly harm developing countries that lack wealthy governments’ resources and typically depend on manufacturing and exports to move up the development ladder. As the World Bank recently noted in cautioning against the use of trade-distorting subsidies, the same problems exist for manufacturing: Poor countries are less integrated into global supply chains, in part because “subsidized exports of industrial goods, including parts and components, prevent developing countries from entering manufacturing value chains,” and “this may especially be the case as they lack the resources to counter the effects of other countries’ subsidies.” The authors further warn that this displacement “can limit the growth potential that trade offers low- and middle-income countries, as participation in manufacturing value chains is typically associated with higher investment and technological spillovers.” Other organizations, such as the IMF and World Trade Organization, have expressed similar concerns about the effects of today’s global subsidy race on the developing world.

A Better Way Forward

Industrial policy in the United States has long been hampered by economic, political, and practical challenges that limit its effectiveness, and it has repeatedly created unintended problems that harm the U.S. and global economies while fomenting government dysfunction along the way. Plenty of warning signs indicate that history is indeed repeating again.

This doesn’t mean that Congress should sit back and simply hope for the best. There are many market-oriented reforms that Washington should pursue to boost U.S. manufacturing and minimize problems associated with industrial policies. This includes eliminating tariffs and other restrictions on imports of key industrial and construction inputs; using international agreements to help U.S. companies access other markets and to expand our industrial base to include close allies; improving the tax treatment of capital investments; reforming NEPA and other burdensome regulations; increasing legal immigration; injecting competition in K-12 and higher education; and enacting other market-based reforms. Global overcapacity, moreover, is best addressed through multilateral dispute settlement, instead of self-defeating, tit-for-tat protectionism.

There’s a long list of time-tested policies that Congress and the administration can pursue to boost strategic industries in the United States and address some of the most pressing challenges facing our country today. Tariffs and subsidies, however, are not on that list.