During the last two-thirds of 2020, progressive policymakers, misguided by mistaken claims of spiking hardship, pushed for unprecedented government assistance to families. Coming after extraordinary federal policy interventions in March and April, this additional assistance proved unnecessary to prevent hardship from rising above its all-time low pre-pandemic levels. With the availability of COVID vaccines and the promise of a spring thaw in COVID transmission, it should have been clear in early 2021 that it was time to prioritize a return to normalcy.

Instead, Congress and the White House—now under unified Democratic control—continued its focus on increasing safety net spending, and together they seized a political opportunity to shift the country toward social democracy. In the process, progressive policymakers have blithely relegated a number of issues to secondary status, including vaccine messaging, availability of in-home COVID testing, withdrawal from Afghanistan, exploding deficits, inflationary pressures, clogged-up supply chains, and sluggish labor force participation.

One particularly important casualty has been the prospects of children—especially poor children—for upward mobility. Since the early days of the pandemic, and especially in 2021, much of the left has single-mindedly focused on poverty and safety net benefits, assuming that reducing poverty is synonymous with expanding opportunity. That this assumption is unwarranted is apparent from long-term trends in poverty and mobility and from the disastrous learning losses experienced by children during the pandemic even as poverty rates have remained in check. It is an assumption embedded in what is perhaps the crowning achievement of progressive policymaking this year—a child allowance that will reduce poverty today but, like anti-poverty policies from an earlier era, threatens to hurt upward mobility in the long run.

We Have Reduced Child Poverty Dramatically Over the Long Run

While it is difficult to believe based on much of the political discourse, child poverty in the United States has never been lower than in 2021. The official child poverty rate was 16.1 percent in 2020, up from 14.4 percent in 2019. Otherwise, one must go all the way back to 1978 to find a rate as low as last year. However, the official rate has well-known flaws that have become more important over time. In particular, the official rate does not count non-cash benefits or refundable tax credits as income, and it does not take into account the long-term decline in taxes. In addition to the official measure, the Census Bureau publishes an annual “supplemental poverty measure” that addresses these shortcomings. By this metric, the child poverty rate was 9.7 percent in 2020—lower than in all of the previous 11 years for which the Census Bureau provides such estimates. Researchers at Columbia University have estimated what this supplemental measure would show going back to 1967, and they confirm that the 2020 poverty rate was lower than ever before. Their most recent monthly poverty estimates indicate that poverty in 2021 has been lower than in 2020.

Even among single mothers and their children, poverty has declined dramatically. The official 2020 rate of 32.1 percent among families headed by a single mother was lower than in any year except 2019. A new study by researchers on the Columbia team finds that among families headed by a single mother not cohabiting with a partner, poverty fell from 65 percent in 1968 to about 54 percent in 1992, on the eve of welfare reform, and to 31 percent in 2014. My estimates for people in families headed by a single mother, using the supplemental poverty measure, show a further decline—from 32 percent in 2014 to 26 percent in 2019 and to 20 percent in 2021. Other research finds even more dramatic declines in poverty and child poverty over the long run.

We Have Failed to Increase Upward Mobility Out of Poverty

The poorest families today are better off than the poorest families in earlier generations, but it is still a problem if upward mobility is low—if children who have the lowest-earning and least-educated parents with the least desirable jobs end up in a similar place themselves. If reducing child poverty were the best way to increase upward mobility, we would expect intergenerational mobility to have increased since the 1960s. Children raised in the poorest families should be less likely over time to become the poorest adults. But in a forthcoming report for the Archbridge Institute, I review the literature on intergenerational economic mobility and provide a large set of original estimates from two different sources. Most studies find either little change in mobility over the past few decades or actual declines—during the same period in which child poverty has fallen dramatically. My own estimates indicate that about half of men raised in the bottom fourth of family income subsequently remained in the bottom fourth as adults. That was true of men born 1952-59 and it was true of men born 1976-83. Using a second data source, 35 to 39 percent of men remained in the bottom fourth having been raised there, whether they were born 1949-51 or 1982-84. Among women, mobility out of the bottom fourth declined, with the share remaining “stuck” rising by 8 to 11 percentage points over these same periods.

This trend is especially striking given that intergenerational mobility increased over the previous 100 years.

What might account for the lack of progress in increasing upward mobility while child poverty fell? One explanation might be that it is too soon to observe rising mobility among recently born children. Typically, intergenerational mobility cannot be measured validly until sons and daughters are at least 30 years old. Much of the decline in poverty has occurred in the past quarter century, so we will need to wait to see how children born during this time fare.

However, poverty did fall before the 1990s economic expansion. The new Columbia study indicates that poverty among single-mother families fell by more than 10 percentage points between the late-‘60s economic peak and the late ‘80s peak. But as noted, upward mobility was flat or declined. One reason may be that while the safety net during this period became much more generous—increasing in value by more than 50 percent for a typical single-parent family between 1965 and 1990—the way that it was woven tended to impede advancement. Before the 1990s, the safety net discouraged work, saving, marriage, investment in skills, and independence. That is to say, from a longer-term and intergenerational perspective, the safety net was also a poverty trap.

A Work-Focused Safety Net and Its Discontents

The 1990s were notable for state and federal policy reforms that both rewarded work and pushed families off welfare programs that had discouraged working. Among progressives, it has become an article of faith that these welfare reforms were harmful to families with children. This perspective has continued to inform progressive policymaking into 2021.

The figures above, however, tell us that poverty among single-mother families has fallen by more than half since the early 1990s. There are very good reasons to think that welfare reform—in combination with increases in work supports such as the earned income tax credit and child tax credit—was a major contributor to the drop in poverty. The value of means-tested safety net benefits received by the typical single-mother family changed relatively little from 1990 to 2019. If it turns out that upward mobility increases for children born in the past two decades, then that would be evidence that it was the distinctive way that we reduced poverty the past 30 years that led to expanded opportunity—not simply how much we spent on the safety net.

This perspective has been rejected out of hand by much of the left over recent years. In 2015 Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer released $2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, which argued that a sizable number of families in America get by on just $2 of income per person per day, that their ranks have increased alarmingly over time, and that the rise was caused by welfare reform. These claims were subsequently unambiguously debunked, but the book ushered in a wave of criticism of welfare reform and advocacy for a safety net founded on no-strings-attached cash payments.

In 2017, Rep. Rosa DeLauro and Sen. Michael Bennet introduced legislation to expand the child tax credit into a “child allowance.” The key feature of this proposal was that the credit would become fully refundable, so that even children in families without a worker were eligible for the full amount. One year later, an influential set of academic researchers, including Edin and Shaefer, published a paper advocating a similar child allowance. The next year, the National Academy of Sciences released a report authored by a committee that included three of the co-authors of the 2018 paper. The report concluded that a child allowance would be the most effective way to reduce child poverty and effectively wrote welfare reform out of the history of anti-poverty policy.

Soon into the 2020 pandemic, many advocates of increased social spending were asserting that the safety net had become too focused on promoting work and could not handle the increase in hardship that the pandemic had inaugurated. In a paper published in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, presented in June 2020, economists Marianne Bitler, Hilary Hoynes, and Diane Schanzenbach asserted that

[O]ver the past several decades the United States has steered its social safety net, which has always been less far-reaching and less funded compared to other rich countries, to focus on work. Through the shift from cash assistance to earnings supplements, and through adding work requirements to programs designed to meet basic food and healthcare needs, the United States has built a social safety net that delivers less insurance and has placed more emphasis on incentivizing work and topping up low earnings. The current system may meet need during times of low unemployment, but it is ill-suited to protect against job loss and high unemployment.

Meanwhile, the push for child allowances picked up steam. A number of Democratic candidates for president, including Bennet, endorsed the idea. The Heroes Act that passed the House in May 2020 included the DeLauro-Bennet proposal. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden included the proposal in his campaign platform later in the race.

As we have seen, the pre-pandemic safety net, combined with the initial response to the pandemic in March and April of 2020, proved effective at containing hardship, contrary to predictions from critics of welfare reform. No matter—despite clear signs that poverty was at an all-time low, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act in March 2021 that included the DeLauro-Bennet child allowance as a one-year expansion of the child tax credit. Almost immediately, progressives began discussing how to make the child allowance permanent, and in April, the Biden administration proposed just that in its American Families Plan. As of this writing, it remains a central component of congressional Democrats’ budget reconciliation legislation.

The child allowance has been just one part of a counterproductive progressive focus on unconditional cash during 2020 and 2021. This focus has already proven costly, and in the long run, it is likely to produce greater costs still. While not the only consequence, lowered upward mobility for poor children may prove to be the most tragic one, just as a poorly-designed safety net in earlier decades may have reduced poverty while impeding opportunity.

Perverse Incentives

Consider, first, the child allowance specifically. Initially, advocates claimed that child allowances do not reduce work because, unlike traditional means-tested programs, they do not phase out as families increase their earnings. This blasé conclusion—and a similar attitude about the potential for child allowances to increase single parenthood—oversimplified a complicated research literature that I summarized in a March report. However, it was not until October that these claims were blown out of the water by a report from University of Chicago economists Kevin Corinth, Bruce Meyer, Matthew Stadnicki, and Derek Wu.

The Chicago team pointed out that while a child allowance did not phase out with earnings, it replaced the old child tax credit’s phase-in. Since the phase-in encouraged work, eliminating it would be expected to reduce work. Relying on estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, they reported that the shift from the old child tax credit to a child allowance would be expected to reduce employment by 1.5 million people, the bulk of them single mothers. The effect they estimated is large enough that it might completely swamp the unprecedented 14-point increase in the employment rate of single mothers from 1994 to 2000. When critics cried that their estimates (really, CBO’s) were extreme, the Chicago team responded with a research note showing that their numbers were consistent not only with the NAS committee’s work but with past research by advocates of child allowances.

If child allowances, like the old safety net before welfare reform, reduce short-term poverty while discouraging work and marriage, then they will do little to diminish more entrenched forms of poverty—multigenerational, geographically concentrated, and social poverty. There are other ways to target both poverty and intergenerational mobility that take seriously concerns about the perverse incentives and unintended consequences of safety net policies. But the focus on poverty and cash benefits during the pandemic has revealed a complete disinterest among many progressives in the complications and limitations of the available evidence.

Learning Loss

Progressives’ emphasis on unconditional cash is likely to hurt child opportunity in a much more direct way in the short-term—one that will have lasting consequences for children and the nation writ large. By placing such a high priority on direct payments to households—including not only child allowances, but stimulus payments, unprecedented unemployment insurance expansions, bigger food stamp benefits, health care subsidies, to say nothing of loan forbearances and eviction moratoriums—progressives neglected what should have been the supreme imperative of preventing kids from falling behind in school.

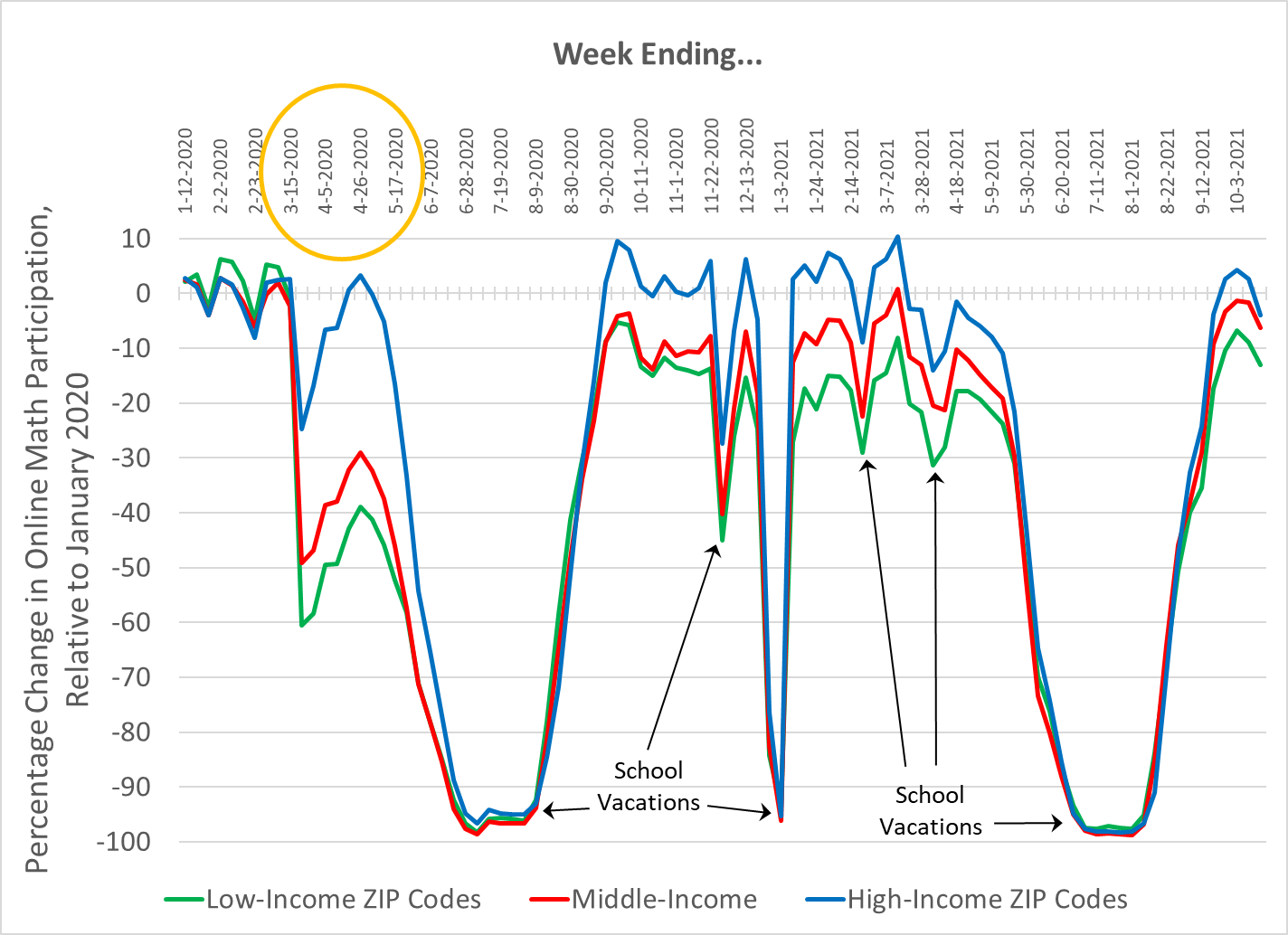

The chart below illustrates what happened to child learning in poor, middle-income, and upper-income ZIP codes over the course of the pandemic. It displays data collected by an online math platform called Zearn and tabulated by Opportunity Insights. The chart shows trends in weekly use of the Zearn website, widely used by elementary schools. Usage is pegged to January 2020, and Opportunity Insights was careful to include in its trend data only schools with significant usage during this month. Values at the top of the chart indicate usage close to the January level (near zero percent change from that month). Lower values mean that in a given week, Zearn usage was below January 2020. At the bottom of the chart, the trends drop below 80 percent of the January 2020 usage, corresponding with summer and holiday vacations.

After the declaration of the national emergency in mid-March 2020, Zearn usage plummeted. (See the weeks circled in yellow.) For lower- and middle-income schools, usage fell to holiday vacation levels or worse for the rest of the school year. Zearn usage in low-income schools dropped by as much as 60 percent and was still down 40 percent when the year ended. Upper-income schools fell by less and fully recovered before the year was out.

Understandably, both schools and federal policymakers were scrambling in the initial weeks and months of the pandemic. However, after the initial policy response in March and April, and once kids limped out of the 2019-20 school year, federal policymakers should have prioritized an Operation Warp Speed addressed at preventing widespread learning losses that could damage a generation of children and permanently reduce the wealth of our nation.

Instead, Congress bickered over stimulus legislation, divided by the issue of aid to states and localities and over the magnitude of direct payments to families. Two months into the 2020-21 school year, 1 in 5 school districts (and over 1 in 4 with an above-average share of nonwhites) was still relying entirely on remote learning. Indeed, by the end of the year, only about half of districts were fully back to in-person learning. Schools that experienced closures and related disruptions disproportionately served disadvantaged students.

We can turn back to the chart to see the consequences. During the 2020-21 school year, low-income students used Zearn about 10 to 20 percent less than in January 2020. Usage in middle-income schools was also down around 10 percent most weeks. In upper-income schools, however, Zearn usage remained roughly at early 2020 levels, falling off toward the end of the year.

This reduced engagement in learning has accumulated over time. Getting back to January 2020 levels of engagement does not erase the earlier months of deficits. The inevitable result is that more children have fallen behind. In Texas, the share of children in grades three through eight meeting grade-level requirements rose from spring of 2016 to spring of 2019, but from 2019 to 2021 the share fell from 39 percent to 34 percent in reading and from 40 to 28 percent in math. For Algebra I students, it fell from 62 percent to 41 percent. In Ohio, learning losses between March 2020 and spring 2021 amounted to one-third to one-half of a year of learning in language arts (depending on the grade level), and one-half to one year of learning in math. The declines were largest for lower-achieving students. Declines in learning also have been quantified in Colorado, Connecticut, Michigan, Tennessee, and a number of other states. When states have provided breakouts by whether schools had in-person or remote learning, the biggest declines were among remote schools.

While there were limits to how quickly and effectively schools could have spent federal funds, it is also the case that policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels failed to mobilize a sufficiently creative response to the educational emergency created by the pandemic. An educational Operation Warp Speed could have prioritized research intended to determine quickly and unambiguously the best ways to re-open schools safely. It could have funded high-quality remote learning platforms to be deployed throughout the country, featuring the best educators in the nation and state-of-the-art apps. It might have created a corps of supplementary teacher’s aides, offered low-income families in-home visitation, canvassed communities to find out who was becoming disconnected from schools, or provided space for remote students when they lacked technology or parental support at home. An ambitious push for summer school or a longer school year could have been organized to encourage parent awareness of the importance of preventing learning losses. It could have provided vouchers or tax credits for learning pods or tutors, or any number of other innovations.

This was a bipartisan failure; there were no calls from the Republican-controlled Senate for anything like an Operation Warp Speed for schools. But that so much of the COVID policy debate centered on the massive spending on families proposed in Democratic bills—when poverty had already been contained—meant that other priorities were given short shrift. What was needed was not necessarily more funds but more attention. A focus on opportunity rather than on poverty might have reoriented debate toward the best ways to avoid learning losses.

It is all the more egregious that policymakers have not made this shift in 2021. With control of the presidency and both houses of Congress, and poverty around the all-time low levels of 2019, Democrats might have pivoted to education. Instead, in March they passed the $1.8 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, including $850 billion toward an expanded CTC, stimulus payments, additional unemployment benefits, and other direct payments to families. Then they shifted to their long-term priorities of green jobs and permanently expanding direct payments to families. ARPA included $126 billion for primary and secondary education, but as my colleague, Nat Malkus, has pointed out, it is unclear whether states even today have spent the $76 billion in school funding provided before ARPA. And the funds have been channeled to schools through conventional routes—and spent in conventional ways—without any consideration of how to support more creative strategies and innovation that might have addressed learning deficits.

In the current school year, Zearn usage is still down 10 percent in low-income schools. While in-person schooling has slowly returned to something resembling normal, the learning losses remain. We will be dealing with their effects for decades to come, but the current policy debate is focused instead on the long-standing policy priorities of Democrats.

Bearing the Cost

Progressive policymaking during the pandemic has betrayed a negligence rooted in a single-minded concern with maximizing the benefits the federal government can transfer to families. Providing social insurance and maintaining a robust safety net are worthy causes. But the bipartisan policy response to the pandemic in March and April 2020 successfully kept poverty at all-time low levels. The continued efforts on the left over the rest of 2020 to swell pandemic relief well beyond these early policies were misguided and distracted from other priorities.

Once Democrats assumed control of the Senate and presidency in 2021, the failure to pivot to other problems became more fully their own and even less defensible. By prioritizing unconditional cash in the American Rescue Plan Act and Build Back Better, progressives have neglected key short- and long-term policy goals other than sending government assistance directly to families. Their safety net policy ignored the threat that such assistance might slow the recovery in the short-run by weakening labor supply and that it might impede upward mobility in the long-run through work and marriage disincentives.

Perhaps worst of all, progressives’ focus on their social democratic agenda perversely neglected the learning losses suffered by children and college students, which disproportionately affected low-income students. But it also distracted them from other immediate national priorities such as the Afghanistan withdrawal, the supply-chain crisis, accelerating inflation, and still-high COVID mortality. With Democrats struggling to pass their agenda in Congress, President Biden’s tanking approval ratings, and a poor Election-Day showing, they are bearing the cost of their inattention to these priorities. And rightfully so.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.