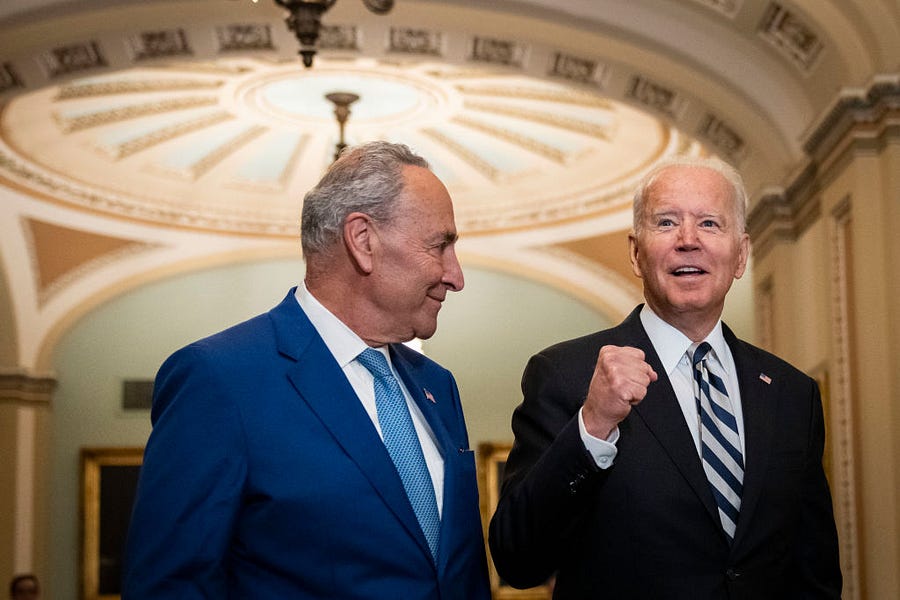

Last week, the Biden administration and congressional Democrats announced an agreement to pursue a $3.5 trillion “human infrastructure” package, which, among other things, would expand Medicare to include dental, hearing and vision benefits. (The administration also endorses lowering the eligibility age from 65 to 60, but that proposal does not appear to be included in the Democratic framework.) Meanwhile, the trustees charged with overseeing the program’s financial health are late with their annual report; when it is finally released, it is likely to warn that the program’s hospital insurance (HI) trust fund will run out of reserves within several years.

The disconnect between the Medicare agenda emerging in Congress and the program’s financial outlook is jarring. Medicare’s rising costs are central to the nation’s fiscal challenges. Before expanding the program further, Congress ought to ensure its current commitments can be met.

While no release date has been announced, the wait for the annual report might end in the coming weeks because it could be awkward politically to push publication beyond summer. Medicare law stipulates that the annual trustees’ report should be delivered to Congress no later than April 1. It is not difficult to see a connection between the current delay and what is occurring in Congress. The administration might want to avoid releasing a report warning of HI insolvency before the deal to expand Medicare is sealed. Last year’s report showed the HI fund running out of reserves in 2026 and projected a 75-year fix would require a 26 percent increase in the payroll tax rate.

The status of the hospital insurance trust fund is sensitive politically because, like Social Security, it can be fully depleted. HI spending, which was $328 billion in 2019, is financed almost entirely from payroll tax revenue. When payments for hospital services escalate more rapidly than tax receipts, the trust fund runs deficits and eventually burns through its reserves. If the trust fund has insufficient funds to cover its expenses, there is no authority in current law to keep paying the full cost of incoming claims (the implication, which has never been fully litigated, is that payments would have to be cut across the board). Congress must step in with corrective legislation before insolvency occurs.

But these troubles are only one part of a larger problem. Hospital insurance accounts for only 41 percent of total Medicare spending. More of the program is now financed out of the supplementary medical insurance (SMI) trust fund, which pays for physician services, other ambulatory care, and prescription drugs. SMI, or Part B, expenditures are covered by premiums collected from the beneficiaries who voluntarily enroll in it, which account for 25 percent of total spending, and payments from the general fund of the Treasury, i.e., taxpayers, covering all other costs. No matter how fast SMI spending escalates, the trust fund always has sufficient reserves because the government, with its borrowing and taxing authority, acts as a backstop.

The perception that SMI is always solvent is a dangerous illusion. SMI’s burden on taxpayers is already high, and it’s rising rapidly. Over the coming decade, the general fund will transfer $5.3 trillion to cover SMI outlays. In 2000, the government’s payment to the trust fund equaled 0.7 percent of GDP. In last year’s report, it was projected to reach 2.8 percent of GDP in 2050.

Medicare’s financial challenges are related to an outdated architecture and the absence of a consensus on how to impose cost discipline consistently, and persistently, across the whole program.

The existence of two Medicare trust funds reflects the insurance environment of the mid-1960s. Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans often bifurcated coverage for hospitalizations and physician fees into separate policies. Medicare, created by Congress in 1965, adopted this model and paid for its two insurance plans, parts A and B, in different ways.

Workers earn hospital insurance coverage with their payroll tax payments (like Social Security, this normally takes 10 years); Medicare beneficiaries pay no additional premium for HI when they become eligible for the program at age 65. Beneficiaries are given the option when they start receiving HI coverage to sign up for Part B (for physician and other services) and Part D (for prescription drugs). Enrollment in these parts of Medicare requires payments of a monthly premium. In 2021, the standard Part B premium is $148.50 per month, and it’s $26 for Part D (higher income beneficiaries are required to pay additional premiums, which are collected through their federal income tax filings).

Congress always intended for Part B of Medicare to receive subsidization from the government’s other tax collections so that the premiums for the program’s enrollees would be affordable. At enactment, the objective was to cover half of all costs with premiums from the enrollees, but that target was quickly abandoned when costs soared. Eventually, Congress settled on 25 percent of program costs as a floor for premium collections, with the other 75 percent coming from general taxation.

Congress also has created separate deductible and co-insurance rules for Medicare’s multiple insurance policies. In HI, beneficiaries must pay a deductible ($1,484 in 2021) when getting admitted to a hospital, and also co-insurance tied to the length of their stays. In Part B, there is a separate deductible ($203 in 2021) and a co-insurance charge of 20 percent of the total fees charged by physicians and other providers. When Part D, for prescription drugs, was added in 2003, it also got a separate deductible ($445 in 2021) and co-payment schedule.

Since it was enacted in 1965, Medicare has never had an annual out-of-pocket limit on how much the program’s beneficiaries must pay in cost-sharing across its multiple parts (in 1989, Congress added a catastrophic benefit to the program, but it was later repealed; in addition, private Medicare Advantage plans are required to put a limit on annual beneficiary expenses).

The potential for high out-of-pocket costs leads many program enrollees to secure supplemental coverage of some sort. Many buy Medigap plans, which are sold and administered by private insurance companies, to cover expenses not covered by Medicare. Others get wrap-around policies from former employers, or enroll in privately administered Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, which often can provide Medicare-covered services with less cost-sharing charged to their enrollees. Enrollment in MA plans now accounts for 40 percent of the program’s participants.

Medigap coverage increases overall Medicare costs. Outside of Medicare Advantage, Medicare is run as a fee-for-service (FFS) policy. The program pays for medically necessary care rendered by licensed providers, with minimal checks on the clinical judgments of individual practitioners. The cost-sharing required of beneficiaries is supposed to provide a check on unnecessary use of services, but Medigap plans eliminate most cost-sharing expenses for their policyholders. Studies show enrollment in Medigap increases Medicare’s costs by about 20 percent.

Navigating the various coverage options for getting Medicare and supplemental insurance is not a simple task, and the government does not make it easy for the beneficiaries to make informed choices. For instance, choosing a Medigap policy is not coordinated with deciding whether to enroll into a Medicare Advantage plan, and there is no easy way to compare the all-in premium costs of the various combinations of available insurance plans.

Congress should see the impending insolvency of HI as a signal that the program requires a more thorough update as it approaches its seventh decade. Medicare’s beneficiaries would lose nothing from an effective reform, as no benefits need to be cut to improve the program’s efficiency. Indeed, Medicare enrollees would have much to gain from better cost discipline, which would lower their out-of-pocket expenses, including for premiums.

Establish a Unified Medicare Trust Fund. The starting point for reform should be a better accounting mechanism for alerting elected leaders to potential financing problems. As noted previously, nearly 60 percent of Medicare spending today is financed out of the SMI trust fund, which is perpetually solvent even though it is imposing immense burdens on both retired and working Americans. Congress should create a new, unified Medicare trust fund that accounts for all of the program’s spending, and then monitor it to ensure solvency and affordability for taxpayers.

Existing hospital insurance taxes would be deposited into the new unified trust fund, as would premium collections for parts B and D. The government’s annual general fund contribution to SMI would continue with the new trust fund, but it would not be unlimited. Instead, it should grow each year with the rate of growth of the national economy to ensure it remains affordable, and also fair, across generations. A unified trust fund, with a limited tap on the general fund, would force Congress to consider measures for controlling all of the program’s escalating costs, not just those associated with the Hospital Insurance trust fund.

Create a Modern Insurance Benefit with Annual Out-of-Pocket Protection. Medicare’s insurance benefit should be updated in the same way as its trust funds, by eliminating today’s fragmentation and multiple parts.

A single Medicare insurance plan should cover all relevant medical expenses (drugs, now covered under Part D, might continue as separate coverage during a transition), with one deductible and cost-sharing that makes sense clinically. The insurance should protect against high annual costs, and tie co-insurance to discretionary care rather than unavoidable hospitalizations. The single, up-front deductible would be set to ensure the redesigned insurance is cost neutral to the current law benefit.

Coordinate Insurance Enrollment for Medicare and Supplemental Coverage. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which administers Medicare, should build a single online enrollment portal to make it easier for beneficiaries to compare the costs of the available coverage options, including supplemental benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans and Medigap insurers. To ease comparisons, the options must be presented in standardized formats so that the premium differences reflect the efficiency of care delivery and not the inclusion or omission of certain services from the policies.

Discipline Costs Through Premium Competition. Many Democrats favor using regulations to control costs, but Medicare is now so reliant on private Medicare Advantage plans that premium competition has more potential to deliver results. MA plans already submit competitive bids to CMS specifying the premium they will charge for Medicare-covered services. Those bids, along with estimates of fee-for-service costs, should be used to calculate the government contribution toward coverage in each market area. Importantly, the government’s contribution should be fixed based on the bids and not increase when beneficiaries select more expensive plans. This design would ensure that the beneficiaries would have strong incentives to enroll in plans offering the best value.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that a version of this reform (sometimes called “premium support”) would reduce program costs by 8 percent, and that the pace of cost escalation would likely slow over time as managed care plans deployed strategies and technology to continually improve their productivity.

Convert Accountable Care Organizations Into Provider-Run Health Plans. The Affordable Care Act authorized the creation of provider-driven managed care plans, called accountable care organizations (ACOs). The objective was to reduce costs for fee-for-service participants by giving doctors and hospitals the ability, and incentive, to engage in more management of the overall costs of patient care, even within Medicare’s traditional FFS structure. ACO-affiliated providers can adopt their own protocols for handling various types of cases (especially those with high expected costs), and steer patients to practitioners who agree to follow the ACO’s guidelines. The objective is to eliminate services that do not improve the health status of patients, while encouraging more use of services that can prevent expensive complications from developing.

ACOs have produced positive but modest results. A major impediment is uncertainty about the populations that ACOs are expected to manage. Most beneficiaries do not choose to get their care through ACOs; instead, they are assigned to them by CMS based on their use of physician services. If claims data show that a beneficiary’s primary physician is affiliated with an ACO, the beneficiary is automatically assigned to the ACO. Most beneficiaries are unaware of this process, and thus have little incentive to cooperate with their ACO’s managed care practices. The loose connection with assigned beneficiaries makes cost control in ACOs much more difficult than it is for MA plans.

Provider-run managed care can play an important role in a reformed Medicare program, but it will continue to disappoint if it does not have stronger incentives for cost control. Its value is in giving hospitals and physicians a pathway to compete directly with insurance-driven Medicare Advantage plans. Congress should allow ACOs to enroll beneficiaries in their plans in the same way MA plans do today, and to offer premium discounts when they are able to cut their expenses.

Foster Price Competition Among Providers for Common Services. Cost discipline need not be limited to competition among managed care plans. The Obama and Trump administrations pushed for greater price transparency from hospitals and physicians to facilitate comparison shopping by consumers for common medical services. The Biden administration can build on the rules already in place by rewarding Medicare beneficiaries when they select lower-priced providers. Advancing this reform will require standardizing what is being priced and allowing consumers to share in the savings relative to benchmarks tied to Medicare’s FFS payment rules.

The Biden administration and Congress, at least for now, are not focused on Medicare’s existing financial challenges, or on reforming the program to make it more resilient and sustainable. Their energies are directed toward expanding Medicare’s commitments to ease the financial burden on current enrollees. In other words, they want Medicare to take on more so that consumers can take on less.

But, as the trustees report will show (whenever it is released), pushing more obligations onto Medicare carries its own risks. The promises already embedded in current law will far outpace the ability of the government to raise taxes to pay for them if health care costs continue to escalate rapidly.

An effective Medicare reform can reduce expenses both for the program’s enrollees and for the government. More efficiency in how care is provided would allow both parties to realize savings. Premium competition between MA plans and FFS alone could reduce costs for beneficiaries by 5 percent (in addition to the 8 percent savings for the government). An improved enrollment process and strong price transparency rules would deliver cost reductions too.

Medicare serves its beneficiaries well, as is demonstrated by its popularity. The program does not need wholesale revision. But key aspects of its original design do need to be updated to ensure it remains as valuable to future enrollees as it has been to those who have benefitted from its first half-century.

James C. Capretta is a senior fellow and holds the Milton Friedman chair at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of the monograph “Market-Driven Medicare Would Set U.S. Health Care on a Better Course,” published this month by AEI.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.