The tumult, bitterness, and historic import of the 2008 Democratic presidential campaign makes it easy to forget that the top two candidates that year … weren’t that different on policy.

The race remained contested through the last day of the primaries, when eventual runner-up Hillary Clinton prevailed over eventual nominee Barack Obama in South Dakota. If you knew nothing about their positions, you might assume from that fact that she and he had basically irreconcilable visions for the party a la Ford versus Reagan in 1976 or Trump versus everyone in 2016. Only a clash of worldviews could divide the left for so many months, one would think.

One would be wrong. The biggest disagreement the neoliberal Clinton had with the neoliberal Obama on domestic policy, as I recall, was whether Americans should be compelled to purchase health insurance under a universal health-care program. (Weird but true: It was Clinton who championed the individual mandate at the time and Obama who opposed it.) The choice between the two mostly boiled down to “vibes.” Should Democrats rally behind the would-be first woman president, a technocratic insider with eight years’ experience as “co-president,” or the would-be first black president, a charismatic young outsider promising drastic change from the Bush administration?

Their “vibes” were distinct but their stances on the issues weren’t—with one crucial exception. In October 2002, then-Sen. Clinton voted to authorize the invasion of Iraq. A few days earlier in Chicago, not-yet-Sen. Obama gave a speech declaring his opposition. “I don’t oppose all wars,” he famously said. “What I am opposed to is a dumb war.”

Whether a pro-war Obama would have defeated Clinton six years later on the strength of “vibes” alone is anyone’s guess, but the fact that his early view of the war seemed prescient to members of his party in 2008 may well have tipped undecideds toward him. A politician who gets The Big Issue of the Day startlingly right has a bright national future.

Why is it, then, that Ron DeSantis remains stuck at 20 percent in national polling despite having gotten The Big Issue of COVID restrictions right in the eyes of Republican voters?

DeSantis is the governor who kept his state’s public schools open during the pandemic; who protected nursing-home residents while the lauded-then-disgraced Andrew Cuomo bungled New York’s response; who went to bat for right-wing vaccine skeptics when he banned the use of vaccine passports by private businesses. He leveraged his antagonism toward COVID caution into a full-fledged political “brand,” replete with merchandise about not letting Florida be “Fauci’d.”

In the end he won reelection by nearly 20 points, a victory so resounding that it seemed like proof of concept that a Republican governor who had resisted public-health orthodoxy more ostentatiously than any other would be an electoral steamroller.

Eight months later, with 2023 already more than half gone, he trails Donald Trump by almost 31 points.

Why did getting it right on The Big Issue of the Day work for Obama but not for DeSantis?

Are COVID politics “over”?

A week before last year’s midterm elections, Michael Brendan Dougherty addressed the conventional wisdom that COVID was no longer top-of-mind for American voters. Maybe not directly, he conceded, but issues that were top-of-mind—inflation and crime, chiefly—were clear byproducts of pandemic dislocation. “The 2022 election is about where you stood on COVID, and the aftermath,” he wrote, framing the stakes.

That made sense given the polling at the time. Midterm elections are outlets for frustration at the governing party even in the best of circumstances; if an enormous red wave crashed down on Congress, as was expected, the sheer scale would suggest that some unusually compelling grievance had unified swing voters behind the minority party. The obvious suspect would be mass discontent at Democratic COVID policies and their many unintended consequences.

When the red wave didn’t arrive (Ron DeSantis’ Florida aside), it appeared that “where you stood on COVID” didn’t matter nearly as much as Dougherty and I assumed.

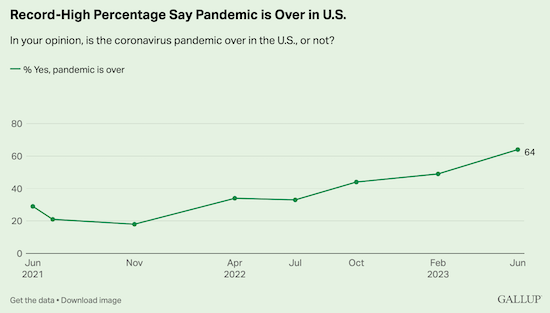

Eight months later, there’s ample reason to believe that voters care less about COVID policies now than they did then. Gallup took the country’s temperature last month and found that pandemic fever has finally broken, even on the left.

That 64 percent who say the pandemic is over includes 51 percent of Democrats, the first time since COVID arrived that a majority of Joe Biden’s party has felt that way. Forty-six percent of adults told Gallup they aren’t worried at all about catching the virus at this point and 43 percent said their lives are completely back to normal, the highest levels recorded on both questions since the Before Times.

This isn’t a case of Americans whistling past the graveyard as another variant of the virus insidiously spreads either. They’re right to be optimistic: Per the CDC, hospitalizations for COVID are at their lowest point ever.

The murder rate is coming down. Inflation is cooling. A recession driven by Fed rate hikes, long expected, has yet to strike. The systemic pandemic disruptions that Dougherty astutely identified seem to be easing, pushing COVID further out of mind.

A simple reason that Obama broke big while DeSantis has struggled to do so, then, is that the war was still very much a live issue in 2008. George W. Bush announced his troop surge aimed at reestablishing control over Iraq on January 10, 2007; Hillary Clinton declared her presidential candidacy 10 days later and Barack Obama was in the race as of February 11. For voters, there was no “turning the page” on the war. The future of America’s adventure in Mesopotamia was on the ballot.

If COVID were still raging, if the two parties were entering year four of the great lockdown debate, Ron DeSantis might be making real gains by attacking Trump as a soft-spined Fauci marionette. It’s his political misfortune to find that The Big Issue of the Day that he was right about is no longer the big issue of the day. Which, frankly, he should have anticipated: A post-policy party like the GOP is destined to be easily distracted. And the sort of swing voter who isn’t post-policy probably has more pressing matters in mind.

Maybe he did anticipate it. Wokeness factors at least as largely in his campaign rhetoric as grumbling about “Faucism” does, after all, another data point about how much the politics of COVID now matter to Republicans.

It’s also DeSantis’ misfortune that his Big Issue has to do with what’s widely viewed as a freak once-in-a-lifetime event. If you’re a swing voter who prefers Democratic policies but resents how the party handled the pandemic, you might convince yourself to set aside your grudge over lockdowns in the belief that we’ll never need to worry about that again. (Fingers crossed!) A swing voter in 2008 didn’t have that luxury with respect to war in the Middle East, particularly when the Republican nominee for president was prone to joking about bomb-bomb-bombing Iran.

DeSantis is also facing stiffer competition in his primary than Obama was, to put it mildly. If Hillary Clinton were at the center of an autocratic personality cult that commanded the loyalty of half the Democratic Party, I dare say the 2008 primary would have turned out differently.

But even if she were as charismatic and as skilled in the politics of dominance as Donald Trump is, she would have struggled to find a persuasive line of attack against Obama over Iraq. She voted for a war that most of her base despised; there was no easy way for her to spin that, nor the fact that Obama had opposed the war early. DeSantis, on the other hand, did lock Florida down, albeit briefly. He reopened after his neighbor to the north, Brian Kemp, already had. And his state lost many thousands of people to COVID, unavoidably, ranking 10th in deaths per capita. He does have some vulnerabilities on this issue.

And he’s running against a guy who’s not just willing and able to make hay of them but who’s not above rehabilitating the loathsome Andrew Cuomo in the name of denigrating DeSantis’ COVID response by comparison. Trump’s attacks on the governor’s pandemic record are a master class in “DARVO,” deflecting accusations about his own mismanagement of the pandemic by reversing them against his accuser. His instinct when he’s called to account for malfeasance is always to muddy the moral waters between himself and his antagonist so that his fans will, at worst, reserve judgment about the charge. Go figure that a Republican voter might listen to his critique of DeSantis and conclude that, whatever Trump’s mistakes on COVID might have been, there’s no reason to think the governor would have done better.

That’s especially true, perhaps, with an issue like the pandemic that was managed mostly at a local level. If your top priority in 2008 was Iraq, the presidency was everything: Barring a very unlikely decision by Congress to defund the war with troops still in the field, choosing a dovish commander-in-chief was the only way to end it. If your top issue as a Republican in 2023 is COVID restrictions, your political energy is better spent electing a conservative governor than a conservative president. It is, after all, the governors who call the shots on public health, as even Donald Trump was once forced to concede.

And if your home state’s too liberal to elect a Republican, you can do what the rest of America seems to be doing by moving to a state where everyone has the same politics that you do.

For numerous reasons, the politics of COVID ain’t what they used to be. Which is not to say that they’re not still around in certain guises.

The residue of COVID politics as the pandemic recedes is vaccine kookery.

It can’t be a coincidence that the two candidates most vocally opposed to COVID restrictions, DeSantis and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., are also the most strident vaccine skeptics in the race. Kennedy is a full-spectrum anti-vaxxer, famously, while DeSantis has staked out what might be described as a just-asking-questions approach to inoculation, playing up the side effects of mRNA jabs.

RFK Jr. comes by his crankery honestly. DeSantis leaned into it cynically, believing I think that noisily doubting the safety of COVID vaccines would serve as shorthand to grassroots Republicans that he, not the cult leader, was the most uncompromising champion against the left with respect to all pandemic rules. He was attempting to do what no Republican since 2015 has managed, creating a populist litmus test which he himself can pass but which Donald Trump cannot.

That strategy might have worked if the pandemic were still top priority for most voters. Because it isn’t, DeSantis’ continued demagoguery of the issue combined with the high profile Kennedy has cut risks marginalizing COVID politics writ large as a boutique subject that’s now mainly a preoccupation of fringers. Which is not promising for the governor’s hoped-for litmus test, nor for his argument that he’s more electable than Trump.

It’s ironic too given how Trump’s critics on the right deride him for obsessing over questions that aren’t of the moment. Some Republican voters might view DeSantis the same way. Between Anthony Fauci and lockdowns on the one hand and who really won the 2020 election on the other, which subject is the type of MAGA voter being courted by the governor of Florida apt to feel more strongly about?

Michelle Goldberg astutely summarized the Kennedy phenomenon, such as it is, in a piece recently for the New York Times:

Still, it’s obvious enough why Kennedy’s sympathizers view it as a moral victory when experts refuse to engage with him. To successfully quarantine certain ideas, you need some sort of social consensus about what is and isn’t beyond the pale. In America, that consensus has broken down. Liberals, justifiably panicked by epistemological chaos, have sometimes tried to reassert consensus by treating more and more subjects—like the lab-leak theory of COVID’s origin—as unworthy of public argument. But the proliferation of taboos can give stigmatized ideas the sheen of secret knowledge. When the boundaries of acceptable discourse are policed too stringently—and with too much unearned certainty—that can be a recipe for red pills.

It’s not that normie voters in the suburbs don’t care about school closures or the lab-leak theory. Of course they do, and did. But to find someone who cares enough about them in 2023 to prioritize them when deciding how to vote in 2024, you likely need to enter a den of redpilled “secret knowledge” where pandemic restrictions and mRNA are just one point on a spectrum of comprehensive skepticism toward establishment received wisdom. Think Joe Rogan’s podcast, where you’re apt to find RFK Jr. declaiming about vaccines or the host himself holding forth about how the 2020 election really was rigged, sort of.

And here we come to another misfortune of Ron DeSantis. If not for the person of Donald Trump, the governor aligning himself so extravagantly with a broad anti-establishment ethos probably would have worked.

It couldn’t have worked for Kennedy because there aren’t enough kooky populists on the left at this moment in history to vault him into serious contention. The modern Democratic Party sees itself as a bulwark of enlightened liberalism against an illiberal authoritarian threat from the right; they’re not going to roll the dice on RFK with Trump 2.0 looming, assuming they ever were.

But Republicans certainly would have rolled the dice on a figure like DeSantis had he convinced them that he’s the most ardent anti-institutionalist in the race. That, again, is what his litmus test on COVID restrictions was about. But you can’t win that test against an opponent who’s so anti-institutionalist that he once attempted a coup, got himself impeached twice, and is presently facing criminal charges in more than one venue.

Who’s more of a populist bad boy, a guy who kept the bars open in Florida or a guy who might need to issue a self-pardon to spring himself from the federal pen?

The painful fact for DeSantis is that most Republicans have moved on from COVID, at least as a gauge of which candidate is best qualified to tame “the system.” The litmus test they’re keen to pass, it seems, is the one that Trump has offered them: Will you allow the “deep state” to turn you against your hero via the filing of baseless criminal charges or will you defy them by nominating him again?

Whatever was left of COVID politics as an electoral gamechanger probably expired once Trump was indicted in Manhattan.

But one never knows. They may come roaring back in the general election if Trump finds hard feelings among defeated DeSantis supporters and concludes he needs to do something conciliatory to woo them back. Championing their guy’s pet issue by attacking Democrats over pandemic restrictions is one way to ingratiate himself to them.

And even if he doesn’t face any lingering bitterness, he might have an incentive to revive COVID politics regardless.

Inflation and crime may be easing but more ominous and durable consequences of the lockdown era have begun to make themselves apparent. The skies have darkened for a generation of American students; as the storm begins to batter them and their parents, voting patterns may shift in unpredictable ways. Republicans would do well to find a nominee who can effectively make the case against the parties responsible instead of an oaf who’s anathema to voters who are otherwise hostile to the Democrats, but they don’t seem inclined. That’s everyone’s misfortune, not just Ron DeSantis’.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.