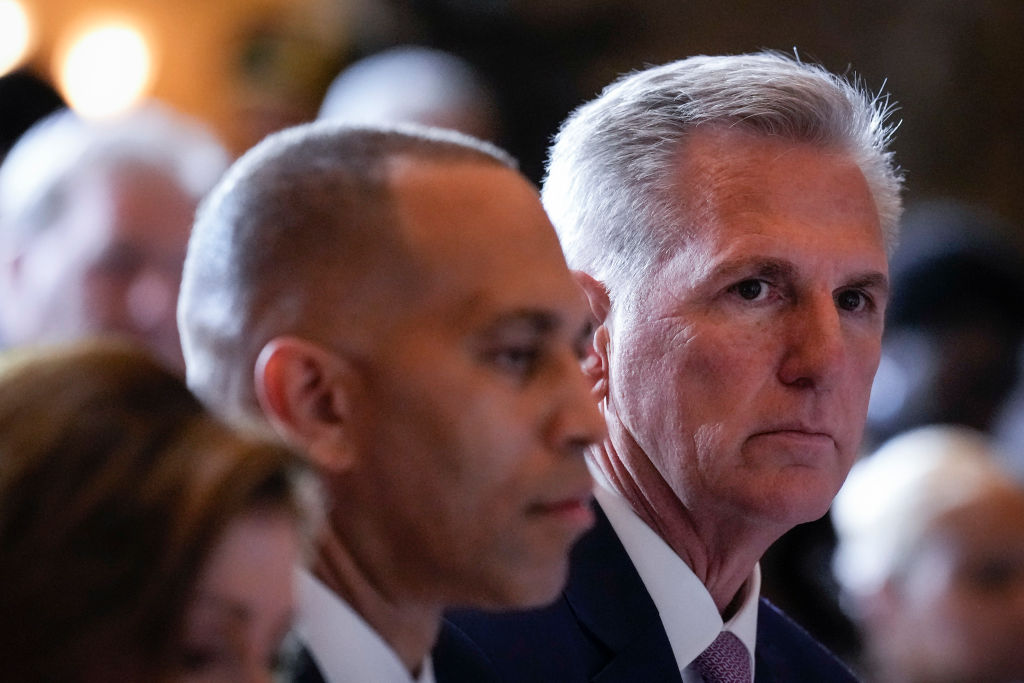

Discrepancies in funding plans for the next fiscal year are setting the House and Senate on a collision course this fall, with a government shutdown hanging in the balance. And House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s need to keep a small bloc of his Republican conference happy to hold onto the Speaker’s gavel could lead to a redux of the debt ceiling battle.

In the House, a group of House Freedom Caucus members and other conservatives have made no secret of their unhappiness with the debt ceiling deal McCarthy reached with President Joe Biden last month, which suspended the debt limit until January 2025 and capped discretionary spending. That has prompted McCarthy to agree to write most appropriations bills for the upcoming fiscal year at much lower spending levels, modeled after the numbers from fiscal year 2022.

The Senate, meanwhile, is largely ignoring the House as its own appropriations process gets underway. In the upper chamber, appropriators are planning to write spending bills for fiscal year 2024 according to the budget targets outlined in the debt ceiling deal, which passed on a bipartisan basis.

House Republicans’ “proposals are not serious,” Sen. Brian Schatz, a Democrat who sits on the Senate Appropriations Committee, tells The Dispatch. “This might as well be a press release.”

But others, especially Democrats, say they’re worried the showdown might gum up government funding.

“After they showed how they were willing to blow up the entire economy with the debt ceiling fight, I can’t predict what they do next,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren tells The Dispatch.

“We’re in for a bit of a fight,” Sen. Bob Menendez, a Democrat, tells The Dispatch. “It’d be foolish for Republicans to shut down the government. They represent one third of the equation. Two thirds, the president and the Senate, is in Democratic hands.”

Republican senators largely downplayed the risk of a shutdown, though only a few seemed inclined to support the more austere numbers the House is pushing.

Sen. Kevin Cramer characterized House Republicans’ approach as “going after things with at least a scalpel if not a butcher knife.” But, he adds: “they have every right to do it. The country needs to get our spending under control.”

The caps outlined in the McCarthy-Biden debt agreement—which McCarthy and allies have referred to as a ceiling—allocate $886 billion for defense spending and $704 billion for non-defense discretionary spending for fiscal year 2024. That doesn’t include emergency spending.

The House Appropriations Committee has currently allocated spending levels for the various subcommittees that would total $1.47 trillion in spending for fiscal year 2024—nearly $120 billion below the debt ceiling deal’s spending caps. House Republicans still plan to spend the $886 billion on the Pentagon and national security, so their cuts would need to come from the non-defense side.

As Haley has covered, such drastic cuts to non-defense discretionary spending are non-starters for the Democratic-controlled Senate and the White House. Democrats already saw the caps as a compromise. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries told reporters last week it represents “an effort by some extreme MAGA Republicans to drive us toward a government shutdown.”

Another wrinkle is that both chambers plan to pass the funding bills through a process known as regular order, with 12 subcommittees approving separate appropriations bills and bringing them to the floor before the fiscal year ends on September 30.

That process hasn’t been used successfully for appropriations bills since 1996, though some committees have approved individual bills in recent years. Instead of going through the individual committee process, lawmakers for the past 27 years have at the last minute bundled together all spending bills in a package called an omnibus. Lawmakers have often reverted to continuing resolutions that keep spending levels consistent until they hammer out the omnibus agreement. For the current fiscal year that began on October 1, Congress didn’t finish the appropriations process until December.

The McCarthy-Biden deal incentivizes regular order by including a provision that would cut discretionary spending by 1 percent if Congress doesn’t pass its annual spending bills by January 1, 2024.

House Republicans’ push to spend less than the caps puts the Senate in the driver’s seat on appropriations, Ben Ritz with the Progressive Policy Institute tells the Dispatch. “What the House has basically done is forfeit its ability to lead on appropriations bills,” he says.

By the time the two chambers have to reconcile the bills, “it’s going to mean that the senators’ priorities are the starting point,” he adds.

“I think what’s happening in the House is pretty irrelevant,” Sen. Chris Murphy, a Democrat, tells The Dispatch. “The Freedom Caucus—which is giving McCarthy fits—they’re not going to vote for the appropriations bills anyway in the end.” He predicted that the bills funding the government will pass with a bipartisan coalition, similar to the group that voted for the debt ceiling deal.

House Republicans, meanwhile, defended their approach: “Republicans control the House, so they are going to be Republican bills, right?” Rep. Mario Díaz-Balart, who is on the Appropriations Committee, tells The Dispatch. “Can we get the 12 bills out of committee? I’m convinced we will.”

When asked if he’s concerned about a shutdown, he quipped: “I’m an appropriator. I can’t worry.”

Rep. Byron Donalds, a House Freedom Caucus Republican, tells The Dispatch he’s “not concerned at all” about a government shutdown. “I’m more concerned that the Senate doesn’t appear to have learned any lessons about overspending,” he adds. “Look, I think in the House, we should be very aggressive in terms of how spending is going to be cut.”

Inching Toward Impeachment?

At first glance, House Republicans seemed to be on the same page Thursday when it came to impeaching President Joe Biden: A procedural vote referring Colorado Rep. Lauren Boebert’s proposed articles of impeachment to the Homeland Security Committee and the Judiciary Committee passed along party lines.

But that basic message—that Boebert’s bill should go through the committee process like any other—is where the unity ends. In fact, Thursday’s vote took place at the urging of Republican leaders seeking to avoid a vote on the articles themselves, which were not expected to pass and thus would have been an embarrassing display of divisions within the GOP conference.

Boebert originally introduced the two articles—which would impeach the president for “abuse of power” and “dereliction of duty” in connection with his immigration policy at the Mexican border—on Tuesday as a privileged resolution. Using a privileged resolution to circumvent party leadership is the same move Florida Rep. Anna Paulina Luna used to force a successful party-line vote to censure California Democratic Rep. Adam Schiff on Wednesday.

While the vote on Schiff—who was censured for misleading comments he made while Donald Trump was president, including during the former president’s first impeachment trial—was an easy vote for both parties, Republican opinions on Boebert’s attempt to impeach Biden are mixed. The GOP’s right flank is chomping at the bit to impeach Biden (as well as to un-impeach Trump), while the rest of the conference wants to see more evidence of conduct rising to the level of “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

“I couldn’t imagine who would vote against it,” Florida Rep. Brian Mast tells The Dispatch when asked about Boebert’s resolution. “As much as I hear rumors that it could happen, I can’t imagine who or why.”

But Oklahoma Rep. Stephanie Bice says she’s waiting to see what evidence of potential wrongdoing emerges from probes such as the Oversight Committee investigation into the Biden family. That “should have been the process from the very beginning,” she says.

“What [Rep. James] Comer’s been doing is going through the process to gather the evidence,” she adds. “We’re not there yet, which is why there hasn’t been anything done prior to now. And someone decided to pull the trigger arbitrarily without having all the ducks in a row.”

Democrats went through an analogous experience when they controlled Congress during the last two years of the Trump administration, with then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi resisting calls from rank-and-file members of her party to impeach Trump until the former president engaged in behavior that she deemed sufficiently serious.

Speaker Kevin McCarthy has a slimmer majority than Pelosi did. So as time goes on, he may feel more intense pressure to bring impeachment articles to the floor to placate his most insurgent members. But he can only afford five defections, which could generate serious political headaches, especially for a purely symbolic measure that would be dead on arrival in the Senate.

Rep. Don Bacon is “adamant” that he won’t consider voting for any impeachment resolution that hasn’t gone through the committee process. But given that some in his party are looking to build “momentum” toward an impeachment vote that can succeed, he expects more resolutions to come: “Nothing would surprise me.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.