Sen. Tom Cotton argued in an op-ed for the New York Times on Wednesday that the Trump administration should deploy the U.S. military to American cities to quell a series of riots. The newspaper’s decision to publish Cotton’s opinion immediately sparked controversy, as some of the newspaper’s employees and many on social media objected. Putting aside that rancor, it is worth revisiting an op-ed published in February that did not receive nearly as much condemnation. That piece was attributed to Sirajuddin Haqqani, a notorious terror kingpin in Afghanistan and northern Pakistan who has been allied with al-Qaeda for many years.

Today, Haqqani is the deputy emir of the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, a totalitarian regime the jihadists have been fighting to resurrect ever since it was toppled by the U.S. and its allies in late 2001.

I note that the piece was attributed to Haqqani, because there are good reasons to suspect he didn’t actually write it. The language employed (including phrases such as “recurring disquiet”) demonstrates a suspiciously refined knowledge of English that Haqqani, a non-native speaker, hasn’t displayed elsewhere throughout his lengthy career.

Even if Haqqani did write the piece, there is much the New York Times should have told readers about him when publishing it. I previously published a summary of Sirajuddin Haqqani’s longstanding, close-knit relationship with al-Qaeda for The Dispatch.

One thing worth noting, in light of the Times saying in response to Cotton’s op-ed that it would be expanding its fact-check operations (and Cotton’s description of the editing process he went through), is that Haqqani’s piece claims that the Taliban wants a system “where the rights of women that are granted by Islam—from the right to education to the right to work—are protected.” As anyone who has seriously studied the Taliban knows, that is a deceptive way of appealing to a Western audience. The rights “granted by Islam” to women, according to the Taliban’s sharia (or Islamic law), are a far cry from what the Times’s audience would find acceptable. Yet, this wordplay made it through the paper’s fact-checking process without any clarification.

The fact-checkers also didn’t inform readers that Sirajuddin Haqqani’s dossier is filled with al-Qaeda ties. The evidence comes from many sources, including first-hand witnesses, official terror designations, press reporting, terrorist media, and files captured in Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad, Pakistan compound in May 2011.

No one can seriously argue that Sirajuddin Haqqani isn’t an al-Qaeda man.

Yet there is no mention of al-Qaeda, let alone a renunciation of the group, in the New York Times op-ed attributed to Sirajuddin.

Some have seized upon the author’s mention of “disruptive groups” as an indication of his willingness to distance the Taliban from al-Qaeda. But as is so often the case these days, that is putting words in the Taliban’s mouth. That phrase could easily refer to the Islamic State’s presence. And if Sirajuddin wanted to specifically disavow al-Qaeda, he could easily do so. The Taliban regularly publishes statements and videos in several languages. The last time Sirajuddin appeared in a production discussing al-Qaeda was in a December 2016 video celebrating the Taliban’s historic alliance with Osama bin Laden and his group. That video was produced by the Haqqanis’ own Manba’ al-Jihad media shop.

Since the New York Times’s publication of the Haqqani op-ed in February, additional evidence has come to light. Earlier this week, a U.N. monitoring team published an analysis claiming that the Taliban’s and the Haqqanis’ alliance with al-Qaeda remains unbroken. The report’s allegations cut against the Trump administration’s claims regarding the agreement it signed with the Taliban on February 29. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has gone so far as to argue that the Taliban has agreed to “work alongside of us to destroy” al-Qaeda.

The text of the U.S.-Taliban agreement says no such thing. And the newly released U.N. report provides additional reasons for skepticism.

The Taliban “regularly consulted with Al Qaeda during negotiations with the United States and offered guarantees that it would honor their historical ties,” the U.N. monitoring team’s report reads.

Member states told the U.N.’s analysts that the Taliban and al-Qaeda “held meetings over the course of 2019 and in early 2020 to discuss cooperation related to operational planning, training and the provision by the Taliban of safe havens for Al Qaeda members inside Afghanistan.” There were six reported high-level “meetings between Al Qaeda and Taliban senior leadership held over the past 12 months.”

Ayman al-Zawahiri himself reportedly met with a delegation of Haqqanis in February of this year, the same month the New York Times ran the op-ed attributed to Sirajuddin Haqqani. This was also around the time the Trump administration and Taliban signed their deal. The delegation allegedly included Yahya Haqqani—Sirajuddin’s brother-in-law and a longtime “liaison” to al-Qaeda. The U.N. monitoring team doesn’t say what came of the meeting, only that the Haqqani team “consulted” with Zawahiri “over the agreement with the United States and the peace process.”

Another meeting reportedly occurred in the spring of 2019, when Hamza bin Laden met with three Taliban representatives in Afghanistan’s southern Helmand Province. The trio of Taliban men met with Hamza “to reassure him personally that the Islamic Emirate would not break its historical ties with Al Qaeda for any price.”

There is much we don’t know about Hamza bin Laden’s purported final months. The White House issued a statement in September 2019 saying he had been killed in a counterterrorism operation, but didn’t explain precisely where or when. The White House also said that Hamza “was responsible for planning and dealing with various terrorist groups,” but didn’t name those specific organizations. According to the U.N. monitoring team’s report, the Taliban was one such group.

Still other high-level meetings between al-Qaeda and the Taliban are referenced in the report. And the U.N.’s analysts write that al-Qaeda and the Haqqani Network, which is an integral part of the Taliban, have even talked about creating a new joint fighting force of 2,000 fighters in eastern Afghanistan.

The U.N. Monitoring Team’s report is sourced to “member states,” which typically do not share their intelligence with the public. This makes it impossible for us to independently corroborate certain details—including those mentioned above. It is possible that secret intelligence, such as intercepts, are cited as the underlying sources, but we simply do not know. There is inherent ambiguity surrounding such matters.

Other parts of the report can be checked and verified. And certain passages are entirely consistent with a well-attested history of the Taliban’s relations with al-Qaeda. For example, the U.N. monitoring team writes that “[r]elations between the Taliban, especially the Haqqani Network, and Al-Qaeda remain close, based on friendship, a history of shared struggle, ideological sympathy and intermarriage.”

Readers of the op-ed published in Sirajuddin Haqqani’s name wouldn’t know that.

Some are heavily invested in the fictitious narrative that there is nothing to the relationship between the Taliban and al-Qaeda. But the jihadists themselves have a way of reminding us that al-Qaeda sits at the nexus of various jihadist groups throughout Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In April, the Pakistani Taliban released a lengthy video lionizing its fallen emir Hakimullah Mehsud, who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in northern Pakistan in 2013. The video was an ostentatious display of the Pakistani Taliban’s own “symbiotic relationship” with al-Qaeda. Multiple al-Qaeda figures were featured, including Osama bin Laden.

Mehsud was responsible for some high-profile operations, including the December 30, 2009, suicide attack at Camp Chapman in Afghanistan. It was one of the deadliest days in the agency’s history, as seven CIA officers were killed. Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the operation, which it jointly conducted with the Pakistani Taliban.

The video tribute to Mehsud glorifies the Camp Chapman bombing at some length. It also pays tribute Mehsud’s role in the May 1, 2010 bombing in Times Square New York, not far from the New York Times’s own offices. Fortunately, that bombing fizzled. But the terrorist responsible, Faisal Shahzad, was directed by Mehsud.

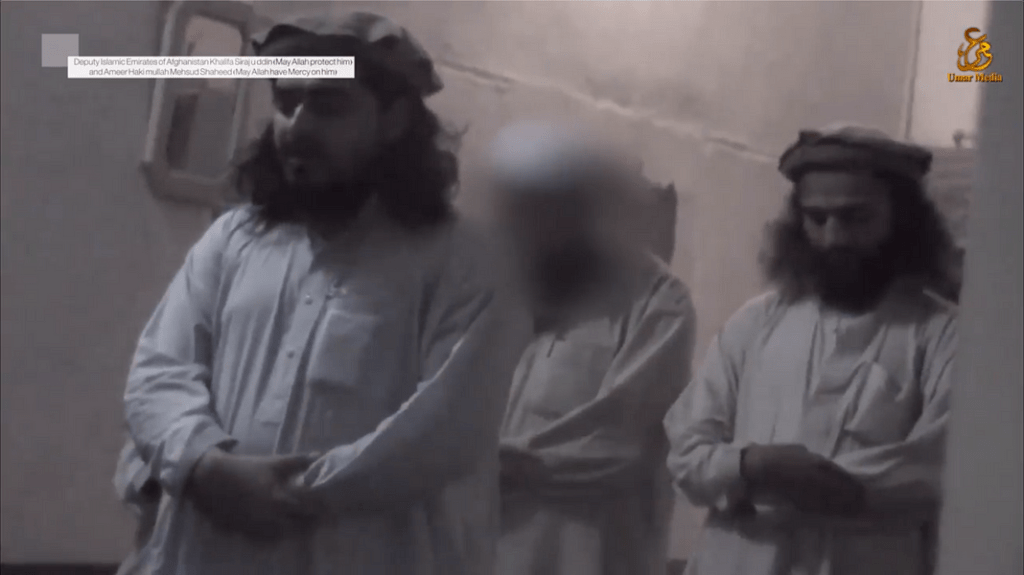

Why does any of this matter for present purposes? Well, at one point in the same video, the Pakistani Taliban includes footage of Hakimullah Mehsud praying alongside Sirajuddin Haqqani.

Haqqani’s face is blurred in the footage, as he refuses to appear in public for security reasons. The text in the upper left hand of the video honors “Khalifa Sirajuddin” as the Deputy Emir of the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate, meaning the Pakistani Taliban’s men continue to consider him to be their rightful ruler.

It has long been known that the Haqqanis harbored the Pakistani Taliban, as well as several other al-Qaeda-affiliated groups, in its strongholds.

But when the New York Times published the op-ed attributed to Haqqani in February, that fact and many others weren’t disclosed.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.