On Monday night, economist Patrick Chovanec surveyed the wreckage of Elon Musk’s Twitter with exasperation. “This place has become a hive of anti-vaxx paranoia,” he sighed. “I think I’m doing some good by rebutting it, but I’m just pissing into the wind. It’s depressing.”

He’s not alone. “I feel like anti-vaxxers on Twitter have gotten noticeably more insane since Elon took over,” said reporter Alex Griswold. “Which isn’t even a critique really… there is something to the sunlight-as-disinfectant idea. It might’ve been better if these folks were more obviously bonkers two years ago.”

How insane have they gotten?

We’ll come back to Damar Hamlin later. The point is, anti-vaxxism does seem to be getting louder and more febrile on social media.

But Twitter isn’t real life, you might reply, and you’d be right. Twitter is a place where you find people using the word “Latinx” unironically. Such creatures are seldom encountered in meatspace.

Still, it’s too pat to dismiss worries about anti-vaxxism with a blithe “Twitter isn’t real life.” The platform is a hub of opinions held by real-life humans; as Mitt Romney might say, Twitter is people, my friend. In fact, Twitter probably underrepresents the extent of anti-vax opinion across the U.S. It’s infamous for amplifying views held by the left-leaning educated class, which is where the idea that it “isn’t real life” comes from. But it ain’t the educated class that’s driving anti-vax sentiment.

The problem with concluding that anti-vaxxism has gotten worse is quantifying it. “Worse” how? Is it more widespread? More outlandish in its beliefs? What does “vaccinated” even mean at this point? Is it the original two shots, the original two shots plus the original booster, or the original two shots plus the original booster plus the bivalent booster that was reformulated to target Omicron variants?

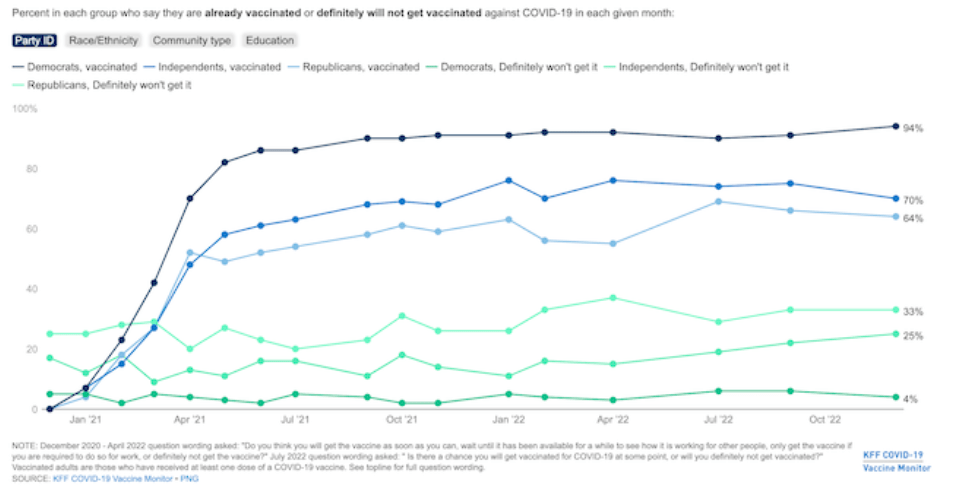

I suspect it’s gotten more widespread. Examine this graph from the Kaiser Family Foundation tracking partisan opinion on vaccination since January 2021.

The share of Democrats who’ve been vaccinated rose between July and December of last year but the share of Republicans and independents dropped—which is strange, since that share should only increase over time. Also strangely, the share of GOPers and indies who said they’d definitely never be vaccinated somehow rose over the same period. Either people are redefining what “vaccinated” means or some are lying to pollsters about their vaccination status, possibly for political reasons.

Which, if so, would suggest that anti-vax sentiment really is spreading, at least on the right.

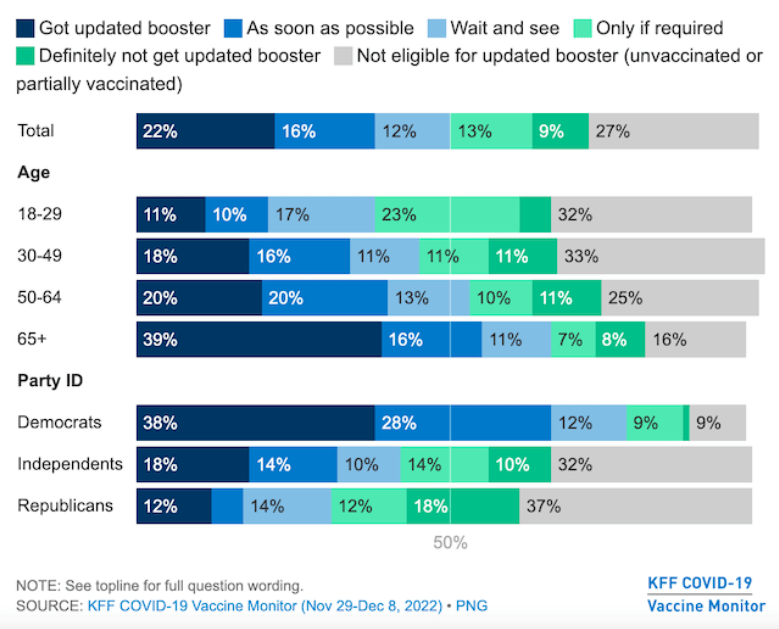

The partisan divide on vaccination also extends to the new booster.

Nearly two-thirds of Democrats have either gotten the bivalent booster or will get it as soon as possible. Around one-third of independents say the same, while just 17 percent of Republicans say so. In all three groups, the share that’s eager to get the new shot is smaller than the share that’s received at least three shots, but the falloff is especially steep on the right. Per KFF, 74 percent of Dems say they’ve had three shots. For Republicans, that share is 37 percent.

In other words, Republicans have gone from being vaxxed and boosted at half the rate of Democrats to showing interest in getting the bivalent booster at roughly one quarter of the rate. That also suggests some growth in anti-vax sentiment on the right. Why?

I have theories.

***

Anytime I complain about Democrats, a few liberals will show up in the comments to grouse that the milquetoast Dispatch conservative writers are at it again, pandering to their right flank by needlessly both-sides-ing an issue.

There really is blame to go around on vaccine hesitancy, though. It’s not 50/50, but liberal COVID hawks overplayed their hand numerous times during the pandemic. And each time they did, it became that much easier for conservatives who were ambivalent about the vaccine in good faith to lean into the “no” column.

The biggest mistake came in the spring of 2021 when the CDC announced that the vaccine prevented infection and therefore those who received the jab could finally unmask. That may have been true at the time but it wasn’t true for long. As spring turned to summer, immunity from the first series of shots waned and the then-dominant variant, Alpha, gave way to the more dangerous Delta. Once vaccinated people started getting sick again, skeptics drew the conclusion that the vaccines “didn’t work.”

They did work. To this day, vaccinated people are less likely to become severely ill and die than the unvaccinated are. But the failed promise that the shot would render recipients immune to the virus left lingering suspicions. No less than Deborah Birx has admitted that she and others overpromised with respect to the vaccine, an error that left some Americans’ faith shaken. Once it became clear that the vaccines also caused serious side effects in exceptional cases, their faith shook further.

The drive to vaccinate kids from COVID made things worse. There’s no fact about the virus better known than that it preys on the old while seldom afflicting the young, especially children, yet the CDC recommends vaccination for everyone from the age of 6 months and up. Some countries in Europe don’t offer the shot to children under 12, seeing too little benefit from it for a cohort that rarely suffers severe disease, but in liberal American strongholds bureaucrats are mulling whether to add the COVID shot to the list of mandatory shots to attend public school.

That imperiousness coupled with stern lectures about “following the science” as the science changed alienated vaccine skeptics further. They were deceived repeatedly about the efficacy of cloth masks, led to believe that they didn’t work and then that they worked better than they did. They suffered through endless, aimless school closures despite the fact that kids have little to fear from infection. They were fed well-meaning nonsense about the “six-feet rule” and installing plastic barriers only to have it walked back later. They were, in some cases, outright lied to for the greater good.

You might defend Fauci, Birx, and the rest on grounds that they were thrust into a once-in-a-century crisis and did the best they could as their knowledge of a novel virus developed. But it’s plain as day how reversals of the sort I’ve described might specifically alienate populists who were already primed to distrust federal authority, along with intellectuals more broadly. Factor in the usual partisan polarization that came with certain liberal COVID hawks having palpably lost their minds on pandemic restrictions and we were destined to have a robust anti-vax constituency on the right even if scientific bureaucrats had performed perfectly.

Which they did not.

None of that answers the question I posed, though. It helps explain why Republicans grew to distrust the vaccine. It doesn’t explain why their distrust has seemed to grow lately.

***

I think “pandemic fatigue” among the vaccinated explains some of it.

After hundreds of millions of infections and vaccinations, there’s enough immunity around that COVID doesn’t feel like much of a risk anymore if you’re under 65. The “milder” pandemic means hospital beds are available to those who need them. The fact that vaccination no longer prevents transmission also reduces society’s collective stake in seeing everyone jabbed. The imperative to convince holdouts to get their shots just isn’t what it was circa 2021. No wonder the share of the population willing to get each successive booster has declined over time.

I have little interest in evangelizing on behalf of the vaccine anymore because how other people feel about it no longer bears much on my own health, if at all. I won’t engage further. But anti-vaxxers? They’ll engage all day long. They’re emotionally invested in being proved right. All of the rhetorical energy in the vaccine debate, insofar as there is a debate, is on their side at this point.

And because it is, populist influencers are leaning into it. No one in America is thirstier for populist approval than Ron DeSantis as he gears up for a tough primary against Trump. It’s not a coincidence that he’s gotten more aggressive at sowing skepticism about the vaccines lately. Just like it’s not a coincidence that his handpicked surgeon general, who was pushing hydroxychloroquine early in the pandemic, is turning up on podcasts where the host is known to say, “Isn’t it a beautiful day to be unvaccinated? It feels so good.”

DeSantis understands that anti-vaxxism has become an element of the populist right’s identity. Some populists confess that they’re losing faith in Trump because he insists on touting Operation Warp Speed as a major achievement of his administration, which it is. (Sample from a QAnon channel on Telegram: “Trump’s just as culpable and every time he continues to push it, more and more want him sitting next to Fauci and Gates at NUREMBERG 2.0”) Many were willing to swallow their doubts earlier in the pandemic out of loyalty to him, I suspect, but as he’s receded politically and DeSantis has emerged, they’ve grown more critical of the vaccine—another possibility for why anti-vaxxism seems to be getting worse.

The more outspoken they get, the more vaccine skepticism grows in importance as a tribal signifier. It’s a truism that anti-vaxxers thrive in low-trust societies, which helps explain the genesis of populist suspicions about the vaccines. But at this stage, evincing vaccine paranoia feels less like a byproduct of heartfelt distrust in authority than a signal of ideological kinship. I wonder how many populists are troubled by Trump’s role in funding the vaccine on the merits relative to how many are troubled to see their cult leader willing to forfeit “One of Us” points by stubbornly refusing to accept populist orthodoxy on the subject.

Pandemic fatigue and political conformism are two factors in growing anti-vaxxism. Another: Twitter. It might not be real life, but it can affect real life.

In late November, Elon Musk announced that the platform would no longer police for COVID misinformation. He announced an amnesty for banned users around the same time, which doubtless meant the return of many anti-vax users suspended by prior management. Some of those users were able to purchase “verified” status from the site under Musk’s ill-fated new verification system, lending their pensées about vaccination a patina of legitimacy.

Twitter has since become quite cozy for vaccine skeptics under the new boss, seemingly by design. When Musk needed someone to write up what the “Twitter files” revealed about the company’s dealings on COVID, he turned to arch-anti-vaxxer Alex Berenson. He pandered to his red-pilled fan base by musing on his feed that Fauci should be prosecuted. Most recently, after a user tweeted about vaccine side effects, the world’s second-richest man responded with, “I had major side effects from my second booster shot. Felt like I was dying for several days. Hopefully, no permanent damage, but I dunno.”

“I dunno.”

The reason users like Chovanec are detecting more anti-vax hysteria on Twitter lately, in other words, is probably because there’s more anti-vax hysteria on Twitter lately, starting at the top. Only Musk knows for sure, but I’d guess many more users are being exposed to vaccine skepticism day to day than was true six months ago.

And the stuff to which they’re being exposed is more sophisticated than garden variety Twitter rants. That’s the fourth factor here.

The timing of Musk’s takeover of the company was fortuitous for vaccine skeptics since it happened to coincide with the release of a major work of anti-vax propaganda. Died Suddenly, a “documentary” that purports to expose a rash of unexplained deaths in vaccinated people, debuted on Rumble in late November. It’s been viewed almost 20 million times since and touted by the likes of Candace Owens and Marjorie Taylor Greene, per The Atlantic. Facebook has made some moves to limit the film’s exposure but on Twitter there’s a dedicated Died Suddenly account with more than 250,000 followers.

Which brings us back to Damar Hamlin.

The popularity of Died Suddenly is such that every celebrity with an unexpected health problem since November has been seized upon excitedly by anti-vaxxers as proof of the film’s thesis. Hamlin, journalist Grant Wahl, singer C.J. Harris, Lisa Marie Presley, and Lynette “Diamond” Hardaway, to name a few: Search their names on Twitter and you’ll find cranks speculating darkly about why they died suddenly. (Almost died suddenly in Hamlin’s case.) In fact, Wahl died of an aortic aneurysm that had likely been growing for years. Hardaway died of a heart condition caused by high blood pressure. Hamlin didn’t die at all, and was most likely the victim of a freak phenomenon known as commotio cordis.

Whether any or all of them were vaccinated is unclear. Hardaway probably wasn’t, as she was an outspoken skeptic of the COVID vaccines. No matter: At her memorial service, her sister suggested that Hardaway had been murdered by the great global vaccination conspiracy, a victim of vaccinated people “shedding” spike proteins onto the unvaccinated. That notion was amplified by Marjorie Taylor Greene on Elon Musk’s Twitter.

You know how conspiracy theories work. The theory remains correct no matter how much evidence emerges to contradict it; ultimately, that evidence will be assimilated somehow into the theory itself. That’s how we get a (probably) unvaccinated person like Hardaway somehow falling victim to the vaccine. And why we see anti-vaxxers straining to explain Damar Hamlin’s survival by theorizing that he actually died and now has a body double making appearances for him. He was vaccinated—we think; he suffered an unexpected health crisis; he must have died suddenly and the truth is being concealed.

Like QAnon, where adherents engage in a competition of sorts to see who can come up with the most creative interpretations of “evidence,” the Died Suddenly phenomenon also seems to be turning into a game. If someone dies (or nearly dies) at an age you wouldn’t expect them to, players are expected to remark quickly, loudly, and pointedly at how unlikely their sudden death is—which sometimes leads to embarrassing errors. That’s how we ended up with cranks marveling at reports of the untimely death of American soccer player Anton Walkes after he perished in … a boating accident.

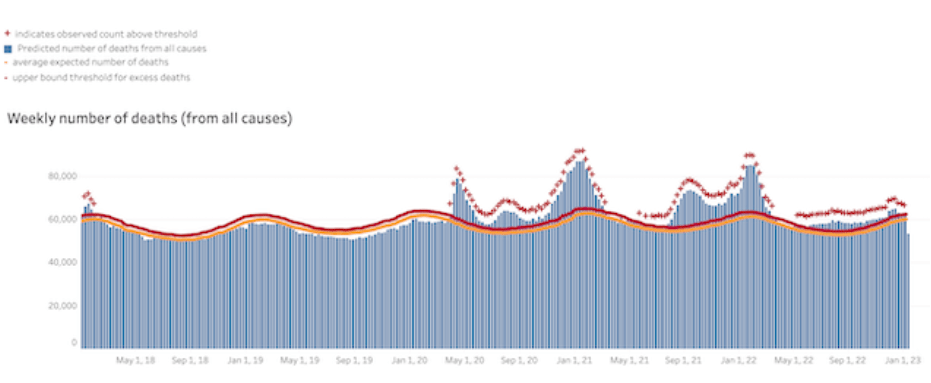

If there were anything to the Died Suddenly hysteria, we’d expect weekly excess mortality in the United States to have risen steadily since early 2021 as more people have gotten vaccinated. More shots mean more suspicious deaths, no? Instead, we find that the peaks of excess deaths in 2021 and early 2022 coincided with ferocious waves of COVID. As COVID leveled off last year, so did total excess deaths.

The vogue for Died Suddenly is probably best understood as a coping mechanism for anti-vaxxers. Just as the idea of “shedding” infectious killer spike proteins is a bizarro-world version of how the virus spreads and kills, suspicions that people are dropping dead from unexpected health problems after a pandemic isn’t outlandish. Americans probably do have more heart problems in the aggregate now than they had three years ago. But it’s not because of the vaccine. It’s because of COVID.

Watching cranks talk each other into believing that people are dropping dead en masse from the jab is a silly phenomenon, but it is a phenomenon. There’s just more anti-vax blather out there lately.

***

Why should we care at this point what Americans think of COVID vaccines?

We shouldn’t, you might say. If the Died Suddenly crowd wants to take their chances with the virus without priming their immune systems, go for it. Most will be fine. For those who aren’t, there’s ivermectin and prayer. Natural selection will do what it does.

I think rising anti-vaxxism is worrisome, though. Like antisemitism, it’s a sign of an unhealthy political culture, a symptom of a society with a fever. And it has literally unhealthy consequences. In 2019 the Kaiser Family Foundation found Democrats and Republicans largely agreed on whether parents should have the right not to vaccinate their kids for measles, mumps, and rubella. Some 86 percent of Dems said parents shouldn’t have that right versus 79 percent of Republicans who said the same. Three years later, there’s been a sea change. Now, 88 percent of Democrats say parents shouldn’t have the right to eschew vaccination for kids. Just 56 percent of Republicans concur.

It’s one thing to say that the COVID vaccine, which has modest benefits for children, shouldn’t be mandatory. But a movement that wants to make the time-tested vaccine for measles optional despite knowing how herd immunity works is a movement further down the path toward obscurantism than any of us should be comfortable with.

Let me borrow a page from my colleagues at The Morning Dispatch in closing and leave you with three pieces on this topic that are Worth Your Time. Read the debunking of Died Suddenly by epidemiologists Katelyn Jetelina and Kristen Panthagani, who work their way through the film’s most outlandish claims to show that the virus is far more threatening to one’s health than the vaccines. (“We have more evidence than for any other vaccine or disease in the history of humans that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines greatly outweigh the risks.”) Read Jonathan Jarry’s withering response to Died Suddenly as well, as he delves into the science of blood clots and how the film uses some footage of people collapsing mysteriously before the vaccines were widely available. Finally, read scientist Eric Topol on the surprisingly good news about the new bivalent booster. It looked underwhelming in early tests against the newest variants of Omicron but the recent data is more encouraging. A second booster might well be Worth Your Time.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.