Happy Thursday! Live within driving distance of Milwaukee? Join Steve, Drucker, Audrey, and fellow members of the Dispatch community for an informal meet-and-greet at Cafe Hollander in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin on August 22—the day before the first Republican presidential primary debate. We’ll provide appetizers and cover beer and wine for a good chunk of the gathering, which will run from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. CDT.

Members are welcome to bring their significant others, and encouraged to invite nonmembers who might be interested in The Dispatch—we’ll be offering special three-month free trials for anyone who attends as the guest. Keep an eye on your inbox today for an email with additional information and registration details, as well as an update on our plans for in-person events this fall.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

- Investigators are still determining an official cause, but video footage and power grid data from early last week suggests the earliest reported blaze on the island of Maui, Hawaii—what is now the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century—was likely caused by downed power lines, toppled in high winds that had been forecasted for days ahead of time. Lawyers representing some residents of Lahaina—the devastated town on the west side of the island—are suing the state’s main utility company, Hawaiian Electric, which is facing increased scrutiny for its decision to keep aging power lines active prior to last week’s strong winds. State officials believe the death toll, now more than 100 people, will continue to rise.

- An explosion at a gas station in Dagestan, a region in southern Russia, killed 35 people and left 115 injured, Russian officials reported Tuesday. The country’s health ministry said 65 of those injured people were hospitalized as of midday Tuesday, with 11 in grave condition. The Monday night explosion was triggered after a fire from a car repair shop spread to a nearby gas station in Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan.

- Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke on the phone with Paul Whelan on Wednesday, according to CNN, connecting with the former marine who has been wrongfully detained at a remote prison camp in Russia for more than four years. The call—during which Blinken reportedly told Whelan to “keep the faith” and that the U.S. is “doing everything we can to bring you home as soon as possible”—follows news last week of a deal to return five Americans detained in Iran. This is apparently Blinken’s second call with Whelan; the two men spoke for the first time in December.

- North Korea confirmed on Wednesday for the first time that it had detained U.S. Army Pvt. Travis King, who sprinted into the country last month while on a tour of the demilitarized zone. North Korean state media criticized the U.S. in its announcement, alleging King had fled to the country to escape “inhuman mistreatment and racial discrimination within the U.S. Army.” There is no verification that King, who had just been released from a South Korean prison after being held on assault charges, actually listed racism as his reason for bolting across the border.

- Fighting between rival militias in Libya’s capital of Tripoli broke out late on Monday and continued into Tuesday, killing 45 and injuring 146 people. The clashes began after the leader of the 444th Brigade militia group was captured by another group, the Special Deterrence Force. The conflict dwindled by Wednesday, with Libyan military troops deploying throughout the city.

- In a court filing on Wednesday, District Attorney Fani Willis of Fulton County, Georgia, proposed a March 4, 2024 trial date for former President Donald Trump and his 18 co-defendants following their indictment Monday related to efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election in Georgia. If the trial did begin on that date—far from a given, considering the various delays and complications expected—it would likely overlap with Georgia’s March 12 presidential primary, and potentially Trump’s late-March trial date in New York on charges of falsifying business records.

- The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals held Wednesday that the abortion drug mifepristone can’t be prescribed via telehealth or shipped in the mail, finding that the Food and Drug Administration’s loosened regulations on access to the drug were unlawful. The decision, however, will not go into effect until the Supreme Court has reviewed the ruling.

- The Republican-led state legislature in North Carolina on Wednesday successfully overrode six vetoes from Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, passing into law three measures having to do with gender and sexuality. One law bars transgender girls and women in the state from competing in women’s sports at the middle, high school, and college level, while another bans gender-transition treatment for minors with limited medical exceptions. One law, modeled on Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act—the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” bill—requires educators to notify parents if a student has asked to be referred to by different pronouns or names.

- GOP Rep. Don Bacon said Monday the FBI had notified him that Chinese spies accessed his emails in a recent hack of Microsoft software. The Washington Post reported last month that the hacking campaign also targeted Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and employees of the State Department.

Afghanistan, Two Years Later

Two years ago, 31-year-old Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Darin Taylor Hoover texted his mom from Kabul.

“Mamma I’m safe,” he wrote. “I love you.”

On August 26, 2021, at the same Kabul airport, Marine Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews spotted a man in the crowd who matched the description of an expected suicide bomber. He sought permission to shoot, but while leadership hesitated in the confusion, the suspect disappeared into the mass of Afghans trying to flee ahead of the Taliban’s takeover.

“Then—a flash, and a massive wave of pressure,” Vargas-Andrews recalled at a March hearing before the House Foreign Affairs committee. “I open my eyes to Marines dead or unconscious lying around me.”

Vargas-Andrews lost an arm and a leg in the bombing, and Hoover was killed—one of 13 service members and at least 170 Afghans dead from the blast. Nearly two years later, congressional oversight of the chaotic withdrawal is grinding forward as the Biden administration tries to tout anti-terrorism successes and Afghan allies linger in immigration limbo.

The Defense Department hasn’t yet made its report on the withdrawal public—releasing it only to certain members of Congress on relevant committees—but the White House and State Department have published portions of their own assessments. As we reported in April, the administration’s summary characterized the withdrawal as messy but largely successful, given the circumstances it had inherited from the Trump administration.

The State Department’s report—released just before a holiday weekend, a common tactic for limiting press attention—went further in acknowledging the withdrawal’s myriad problems, including unclear communication about evacuation priorities. “Senior administration officials had not made clear decisions regarding the universe of at-risk Afghans who would be included by the time the operation started nor had they determined where those Afghans would be taken” the assessment read. The report also faulted the State Department for failing to appoint a point-person to oversee the effort, and for allowing members of Congress and others to contact workers on the ground with requests for evacuations of specific people—diverting them from organizing the evacuations of larger groups.

The report also recommended the State Department prepare better for worst-case scenarios and listen to a broader spectrum of opinions about potential crises. “The sudden departure of President [Ashraf] Ghani from Kabul and the fall of the city to the Taliban happened with a speed that caught almost all close observers by surprise,” it noted. Key word: almost. “There had been warning signs that prospects the Afghan government forces would defend Kabul and hold out for a possible negotiated transfer of power were evaporating.”

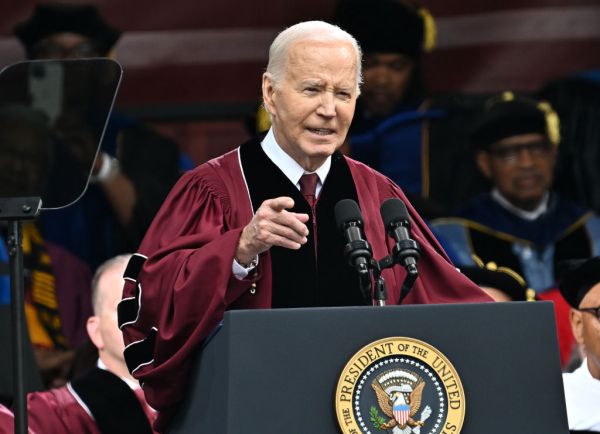

President Joe Biden has stood by the withdrawal and touted the lack of terrorist attacks against the U.S. emanating from Afghanistan. “I said al-Qaeda wouldn’t be there,” Biden declared in June. “I said we’d get help from the Taliban. What’s happening now? What’s going on? Read your press. I was right.” The administration has cited a drone strike killing al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri as evidence of the U.S.’s ability to fight terrorism in Afghanistan without boots on the ground. A September 2022 National Intelligence Council assessment concluded al-Qaeda’s limited presence in Afghanistan won’t pose a threat to the U.S. through at least 2024.

But as GOP Rep. Michael McCaul pointed out, al-Zawahiri was found living in the Kabul home of a senior Taliban official. “It is completely divorced from reality for President Biden to claim that al-Qaeda is no longer operating in Afghanistan or that the Taliban has somehow become our national security partner in the region,” the House Foreign Affairs Committee chairman said in a statement. And despite the Taliban’s opposition, Islamic State affiliate ISIS-K has gained some ground in the country, with an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 affiliated fighters and family members in Afghanistan. As a United Nations analysis concluded recently, “the group has adapted its strategy, embedding itself with local populations, and has exercised caution in choosing battles that are likely to result in limited losses.”

Inside the country, conditions have continued to deteriorate for Afghan civilians. The Taliban has issued more than 50 new restrictions on women, cutting them off from: school after sixth grade, parks, employment for international groups, and solo travel. While the economy hasn’t entered the tailspin seen during Taliban rule in the 1990s, its degraded equilibrium has left many Afghans in poverty—and the United Nations reports 4 million Afghans are acutely malnourished.

That includes Afghans who worked for the United States but didn’t make it out in the evacuation—there are some 152,000 SIV applicants still in Afghanistan as of April. They’re dodging the Taliban while navigating the byzantine process of health inspections, embassy appointments outside the country, and proving how long they worked for the U.S. even if the contractors that employed them have since gone defunct. Applicants have reportedly been turned down over clerical issues like misspelled names or formatting differences in dates. “If the Taliban finds me, they will not ask me how many days I worked for the U.S. Army,” one applicant told No One Left Behind, a group helping Afghan SIV seekers. “If the Taliban finds me, they will kill me.”

The government is making marginal improvements in this process. The State Department has worked to speed up processing of these applications—it’s reportedly now down to a mere 314 days. The Pentagon, meanwhile, recently asked contractors to suggest projects making it easier to verify employment records for SIV seekers.

More than 76,000 Afghans evacuated to the United States without an SIV were brought in on humanitarian parole, which doesn’t include a pathway to legal permanent residency short of a successful SIV or asylum claim. The initial parole lasted two years before parolees became subject to deportation, but the White House has announced those affected can apply for a 24-month extension. A bipartisan group of lawmakers has also reintroduced the Afghan Adjustment Act, which would expand SIV eligibility to groups like Afghan Air Force veterans and create a permanent residency pathway—after more security vetting—to Afghans here on humanitarian parole. Similar legislation failed to pass the previous Congress.

Meanwhile, people like Vargas-Andrews and Gold Star family members of service members killed in the Kabul airport attack still argue the Biden administration hasn’t sufficiently reckoned with the planning errors that contributed to the withdrawal’s chaos. “Do what our son did,” Staff Sgt. Darin Taylor Hoover’s father, Darin Hoover, urged administration and military leaders at a hearing earlier this month. “Be a grown-ass man. Admit to your mistakes, learn from them, so that this doesn’t happen ever, ever again.”

Worth Your Time

- For Law & Liberty, Stephanie Slade highlights the political genius of the Bill of Rights. “The drafters of the Constitution were initially opposed to including a declaration of rights. First of all, they thought that it was unnecessary, since the main text endowed government with only those powers they had specified,” she writes. “Second of all, they worried, not unreasonably, that putting some rights down on paper would lead to a belief that no other rights were protected. Nonetheless, many Americans balked. Having won their freedom from despotism abroad, people wanted a written guarantee against despotism at home. And so the Bill of Rights was born. The genius of those ten amendments is that they take whole issues off the political table. In effect, the Bill of Rights says that there are some things the government may not do—not even if the duly elected president or a bipartisan majority in Congress thinks it would be for the best. Most regulations on speech fall into this category: Under the First Amendment, it simply doesn’t matter how many Americans think blasphemy, or flag burning, or speaking out against gay marriage should be illegal. In a sense, the Bill of Rights attempts to remove certain questions from the political sphere. This is a beautiful instantiation of the classically liberal idea that coexistence is possible through mutual forbearance. When we agree upfront to forgo the use of state power to make others live the way we like, we can secure our own right, regardless of who may hold political office at a given moment, not to be forced to live the way they like.”

Bring This Energy to Your Day Today

Presented Without Comment

The Guardian: NATO Official Apologizes Over Suggestion Ukraine Could Give Up Land for Membership

Also Presented Without Comment

Radio Free Europe: Wagner Mercenary Group Registered in Belarus as Educational Organization

Also Also Presented Without Comment

The Recount: New York City Mayor Eric Adams Says He’s ‘Gandhi-Like’ at a Flag-Raising Ceremony for India on Its Independence Day

Toeing the Company Line

- In the newsletters: Scott argues (🔒) supply and demand is actually the best way to explain the housing market, Sarah ranks the four Trump indictments by strength, Jonah explains why (🔒) the latest controversy over a viral song shows the right really does care about the elites they claim to hate, and Nick charts (🔒) Democrats’ best-case scenario for 2024.

- On the podcasts: David and Sarah are joined by Professor Bradley Rebeiro to talk about Frederick Douglass, while Jonah and AEI senior fellow Ken Pollack discuss U.S. policy toward Iran.

- On the site: Price offers a comprehensive breakdown of the various allegations swirling around Hunter Biden and his family, Kevin examines the New Right’s sudden fondness for socialized medicine, and former Heritage Foundation Executive Vice President Kim Holmes warns that same New Right is dooming conservatism.

Let Us Know

How should the Biden administration respond today to its Afghanistan withdrawal from two years ago? What should it do to ensure Afghans who served alongside U.S. personnel don’t have to wait 314 days to have their visas processed while remaining in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan?